D3 lymph node dissection improves perioperative outcomes and overall survival in patients with cT2N0 colorectal cancer

Highlight box

Key findings

• D3 lymph node dissection (LND) improves perioperative outcomes and overall survival (OS) in patients with cT2N0 colorectal cancer (CRC).

• D3 LND with less intraoperative blood loss, fewer postoperative complications and a briefer average hospital stay.

What is known and what is new?

• There are some differences in the concept of surgery for CRC in Japan and Europe and the United States. In terms of cT2N0 CRC. There is still considerable controversy whether D2 or D3 LND is indicated in Japanese CRC treatment guidelines.

• D3 LND improves perioperative outcomes and OS in patients with cT2N0 CRC.

• However, only 31.3–42.1% of cT2 CRC ultimately confirmed as pT2 CRC.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Accurate preoperative diagnostics are critical for proper surgical management for cT2N0 CRC.

• For CRC accurately diagnosed as cT2, D3 LND is recommended.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide (1). In Japan, the number of CRC-related deaths continues to increase (2). Radical resection currently remains the preferred treatment for CRC with non-distant metastases. The Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) advises careful dissection along embryonic planes, but degrees of dissection depend on depths of nodal metastasis and tumor invasion observed before or during surgery. D3 lymph node dissection (D3 LND) is warranted if lymph node metastasis is suspected or tumor depth of cT3 or cT4 is likely, reserving D2 LND for T1bN0 CRC. In terms of cT2N0 tumors, there is still considerable controversy whether D2 or D3 LND is indicated (2).

During a prior study, we found that radical D3 LND significantly improved survival outcomes in patients with pT2 CRC (3). However, some disparities between findings of preoperative imaging and postoperative pathologic assessment were still apparent (4). In actual clinical practice, there is no consensus yet on extent of LND (D2 vs. D3) indicated for cT2N0 CRC. Propensity score matching (PSM) has been widely used in clinical studies to minimize the impact of confounding variables among groups (5). The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of D3 LND on survival in patients with cT2N0 CRC. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-2024-980/rc).

Methods

Scope of LNDs

All tumor (T) and LND classifications adhered to guidelines of the JSCCR (7th edition). Mesenteric lymph nodes are thereby separable into pericolic, intermediate, and apical compartments. D1 LND is confined to pericolic lymph nodes, whereas D2 LND is directed at both pericolic and intermediate sectors, and the dissection of pericolic, intermediate, and apical lymph nodes is defined as D3 LND (6) (Figure 1). In radical rectal cancer resection and left-sided colectomy, to the root of the IMA, the LND exposing the abdominal aorta is defined as D3 LND, and the LND at the level of the left colonic artery only is defined as D2 LND. For radical resection of right colon cancer, the boundary of the D3 LND is the left margin of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV). If the LND just reached the right edge of the SMV, it is counted as D2 LND. The Japanese CRC treatment guidelines clearly state that D3 LND should be performed when lymph node metastasis or T3 or T4 tumor depth is suspected or when the biological characteristics of CRC are poorly differentiated, undifferentiated, sig-ring cell carcinoma.

Data collection

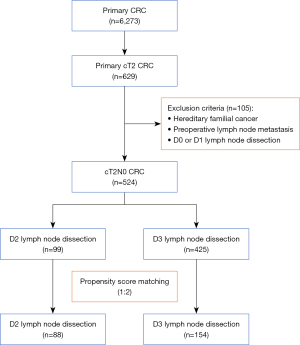

This retrospective cohort study accessed data collected from April 2007 to December 2020 at Saitama Medical University International Medical Center in Japan. The institution’s Ethics Committee of Saitama Medical University International Medical Center approved our study (Ethics Board Registration No. 19-006). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. A total of 6,273 patients submitting to surgical resections of CRC were eligible. We excluded those with pT1, pT3, and pT4 tumors, leaving 629 candidates with pathologically confirmed T2 CRC for study. Familial adenomatous polyposis, preoperative lymph node metastasis, and D0 or D1 LND were also grounds for exclusion (Figure 2). All subjects granted written informed consent preoperatively.

PSM served to balance differences in baseline variables, and multivariate regression models were used to identify potential independent risk factors. The following parameters were incorporated into a multivariate model for PSM: sex, age, body mass index (BMI), tumor location, family history of cancer, abdominal surgery history, operative method, tumor size, postoperative complications, gross tumor type, proximal and distal resection margins, perineural infiltration, lymphatic invasion, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels, vascular invasion, lymph node metastasis, and pathologic stage.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the differences in overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) by LND level (D2 vs. D3). To evaluate the differences in categorical variables, Chi-square test and Fisher’s precision tests were applied. Kaplan-Meier plots provided estimates of OS and RFS. All statistical computations relied on standard software (SPSS v22; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA), setting significance at P<0.05.

Results

A total of 524 patients with cT2N0 CRC qualified for study, 99 (18.9%) and 425 (81.1%) undergoing D2 and D3 LND, respectively (Figure 2). By comparison, members of the D3 (vs. D2) LND group were younger (<70 years: 58.8% vs. 32.3%; P<0.001) and more inclined to rectal cancer (52.2% vs. 36.4%; P=0.006), with a higher proportion of laparoscopic surgeries performed (96.0% vs. 79.8%; P<0.001). Overall, the D3 LND group showed lower CEA levels (<5 ng/mL: 87.5% vs. 78.8%; P=0.024), and fewer group members had histories of abdominal surgery (36.7% vs. 50.5%; P=0.016). Postoperative complications were also less frequent in the D3 (vs. D2) group (15.1% vs. 29.3%; P=0.001), there were significantly fewer instances of blood loss >100 mL (8.9% vs. 19.2%; P=0.006), and hospital stays were briefer [mean ± standard deviation (SD): 9.1±8.2 vs. 11.8±9.0 days; P=0.008]. The two groups did not differ significantly regarding sex, BMI, comorbidity, operative time, and time to first food intake (Table 1).

Table 1

| Parameters | Before PSM | After PSM (1:2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D2 LND (n=99) | D3 LND (n=425) | P value | D2 LND (n=88) | D3 LND (n=154) | P value | ||

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||

| Male | 66 (66.7) | 247 (58.1) | N.S. | 60 (68.2) | 92 (59.7) | N.S. | |

| Female | 33 (33.3) | 178 (41.9) | 28 (31.8) | 62 (40.3) | |||

| Age (years), n (%) | |||||||

| <70 | 32 (32.3) | 250 (58.8) | <0.001 | 28 (31.8) | 51 (33.1) | N.S. | |

| ≥70 | 67 (67.7) | 175 (41.2) | 60 (68.2) | 103 (66.9) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 23.0±3.58 | 22.8±3.30 | N.S. | 23.0±3.46 | 22.9±3.71 | N.S. | |

| CEA (ng/mL), n (%) | |||||||

| <5 | 78 (78.8) | 372 (87.5) | 0.024 | 69 (78.4) | 129 (83.8) | N.S. | |

| ≥5 | 21 (21.2) | 52 (12.5) | 19 (21.6) | 25 (16.2) | |||

| Tumor location, n (%) | |||||||

| Colon | 63 (63.6) | 203 (47.8) | 0.006 | 57 (64.8) | 94 (61.0) | N.S. | |

| Rectum | 36 (36.4) | 222 (52.2) | 31 (35.2) | 60 (39.0) | |||

| Family tumor history, n (%) | |||||||

| No | 74 (74.7) | 372 (87.5) | 0.002 | 70 (79.5) | 131 (85.1) | N.S. | |

| Yes | 25 (25.3) | 53 (12.5) | 18 (20.5) | 23 (14.9) | |||

| History of abdominal surgery, n (%) | |||||||

| No | 49 (49.5) | 269 (63.3) | 0.016 | 46 (52.3) | 89 (57.8) | N.S. | |

| Yes | 50 (50.5) | 156 (36.7) | 42 (47.7) | 65 (42.2) | |||

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |||||||

| No | 25 (25.3) | 145 (34.1) | N.S. | 23 (26.1) | 46 (29.9) | N.S. | |

| Yes | 74 (74.7) | 280 (65.9) | 65 (73.9) | 108 (70.1) | |||

| Operative method, n (%) | |||||||

| Laparoscopic surgery | 79 (79.8) | 408 (96.0) | <0.001 | 78 (88.6) | 141 (91.6) | N.S. | |

| Open surgery | 20 (20.2) | 17 (4.0) | 10 (11.4) | 13 (8.4) | |||

| Operative time (min), mean ± SD | 206±86.1 | 209±69.7 | N.S. | 202±79.0 | 205±74.2 | N.S. | |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | |||||||

| No | 70 (70.7) | 361 (84.9) | 0.001 | 64 (72.7) | 117 (76.0) | N.S. | |

| Yes | 29 (29.3) | 64 (15.1) | 24 (27.3) | 37 (24.0) | |||

| Operative blood loss (mL), n (%) | |||||||

| <100 | 80 (80.8) | 387 (91.1) | 0.006 | 77 (87.5) | 140 (90.9) | N.S. | |

| ≥100 | 19 (19.2) | 38 (8.9) | 11 (12.5) | 14 (9.1) | |||

| Hospital stays (days), mean ± SD | 11.8±9.00 | 9.13±8.24 | 0.008 | 11.4±9.02 | 10.5±12.2 | N.S. | |

| First food intake (days), mean ± SD | 3.91±3.20 | 3.49±2.67 | N.S. | 3.93±3.31 | 3.56±2.42 | N.S. | |

BMI, body mass index; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; LND, lymph node dissection; N.S., not significant; PSM, propensity score matching; SD, standard deviation.

Postoperative pathologic findings revealed significantly shorter distal resection margins in the D3 (vs. D2) LND group (mean ± SD: 6.18±4.31 vs. 7.35±4.80 cm; P=0.033). In addition, there were comparatively more tumors of infiltrating or ulcerative type (60.2% vs. 48.5%; P=0.043) and more harvested lymph nodes (mean ± SD: 22.6±10.5 vs. 19.4±8.3; P=0.001), although nodal metastasis did not differ significantly by LND level [D3, 26 (26.6%); D2, 113 (24.2%)]. Both groups likewise proved similar in tumor size, proximal resection margins, histotypes, infiltrative patterns, and signs of lymphatic or venous invasion, with no significant differences in depths of infiltration (T) or postoperative pathologic classifications (Table 2).

Table 2

| Parameters | Before PSM | After PSM (1:2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D2 LND (n=99) | D3 LND (n=425) | P value | D2 LND (n=88) | D3 LND (n=154) | P value | ||

| Tumor size (cm), n (%) | |||||||

| <2 | 27 (27.3) | 81 (19.1) | N.S. | 21 (23.9) | 28 (18.2) | N.S. | |

| ≥2 | 72 (72.7) | 344 (80.9) | 67 (76.1) | 126 (81.8) | |||

| Proximal resection margin (cm), mean ± SD | 11.9±4.67 | 12.9±4.49 | N.S. | 12.3±4.74 | 12.9±5.32 | N.S. | |

| Distal resection margin (cm), mean ± SD | 7.35±4.80 | 6.18±4.31 | 0.033 | 7.53±4.96 | 7.02±4.45 | N.S. | |

| Gross features, n (%) | |||||||

| Protruding | 51 (51.5) | 169 (39.8) | 0.043 | 41 (46.6) | 63 (40.9) | N.S. | |

| Infiltrate or ulcerative | 48 (48.5) | 256 (60.2) | 47 (53.4) | 91 (59.1) | |||

| Tumor histology, n (%) | |||||||

| Well, Mod | 45 (45.5) | 160 (37.6) | N.S. | 41 (46.6) | 58 (37.7) | N.S. | |

| Poor, Sig, Muc | 54 (54.5) | 265 (62.4) | 47 (53.4) | 96 (62.3) | |||

| Infiltration pattern, n (%) | |||||||

| a | 14 (14.1) | 57 (13.4) | N.S. | 13 (14.8) | 21 (13.6) | N.S. | |

| b and c | 85 (85.9) | 368 (86.6) | 75 (85.2) | 133 (86.4) | |||

| Lymphatic invasion, n (%) | |||||||

| No | 77 (77.8) | 315 (74.1) | N.S. | 67 (76.1) | 115 (74.7) | N.S. | |

| Yes | 22 (22.2) | 110 (25.9) | 21 (23.9) | 39 (25.3) | |||

| Venous invasion, n (%) | |||||||

| No | 45 (45.5) | 202 (47.5) | N.S. | 39 (44.3) | 81 (52.6) | N.S. | |

| Yes | 54 (54.5) | 223 (52.5) | 49 (55.7) | 73 (47.4) | |||

| Excised lymph nodes, mean ± SD | 19.4±8.33 | 22.6±10.5 | 0.001 | 19.3±8.32 | 22.9±10.6 | 0.003 | |

| pT class, n (%) | |||||||

| 0 | 4 (4.0) | 18 (4.2) | N.S. | 4 (4.5) | 4 (2.6) | N.S. | |

| 1 | 35 (35.4) | 119 (28.0) | 29 (33.0) | 42 (27.3) | |||

| 2 | 31 (31.3) | 179 (42.1) | 29 (33.0) | 63 (40.9) | |||

| 3 | 26 (26.3) | 101 (23.8) | 23 (26.1) | 43 (27.9) | |||

| 4 | 3 (3.0) | 8 (1.9) | 3 (3.4) | 2 (1.3) | |||

| Nodal metastasis, n (%) | |||||||

| No | 75 (75.8) | 312 (73.4) | N.S. | 65 (73.9) | 116 (75.3) | N.S. | |

| Yes | 24 (24.2) | 113 (26.6) | 23 (26.1) | 38 (24.7) | |||

| Pathologic stage, n (%) | |||||||

| 0 | 4 (4.0) | 17 (4.0) | N.S. | 4 (4.5) | 4 (2.6) | N.S. | |

| I | 54 (54.5) | 237 (55.8) | 47 (53.4) | 84 (54.5) | |||

| II | 16 (16.2) | 54 (12.7) | 14 (15.9) | 26 (16.9) | |||

| III | 22 (22.2) | 106 (24.9) | 21 (23.9) | 37 (24.0) | |||

| IV | 3 (3.0) | 11 (2.6) | 2 (2.3) | 3 (1.9) | |||

Protruding: type 0, superficial; type 1, protuberant, infiltrative, or ulcerative; type 2, expansive ulceration; type 3, infiltrative/ulcerating; type 4, diffusely ulcerating. Well, well-differentiated adenocarcinoma; Mod, moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma; Poor, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma; Muc, mucinous carcinoma; Sig, signet-ring carcinoma; LND, lymph node dissection; N.S., not significant; PSM, propensity score matching; SD, standard deviation.

In analyzing long-term outcomes of LND subsets, we found D3 (vs. D2) LND to be associated with significantly better 5-year OS (94.4% vs. 83.8%; P=0.001) (Figure 3A), although the same was not true of RFS (92.0% vs. 94.9%; P=0.340) (Figure 3B). Cox regression analysis, performed before PSM, was invoked to assess effects of various parameters on patient prognosis. D3 LND subsequently became an important independent predictor of OS [hazard ratio (HR) =2.0; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.0–3.9; P=0.04], as did age <70 years (HR =2.9; 95% CI: 1.4–6.0; P=0.004) and pathologic T0–1 classification (HR =2.6; 95% CI: 1.0–6.8; P=0.049) (Table 3).

Table 3

| Variables | OS before PSM | OS after PSM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| LND (D3 vs. D2) | 2 | 1–3.9 | 0.04 | 2.3 | 1–5.1 | 0.04 | |

| Age (<70 vs. ≥70 years) | 2.9 | 1.4–6 | 0.004 | 6.3 | 1.4–28 | 0.01 | |

| Tumor family history (no vs. yes) | 0.57 | 0.3–1.1 | 0.09 | 0.36 | 0.15–0.86 | 0.02 | |

| Operative method (laparoscopic vs. open) | 1.6 | 0.68–4 | 0.27 | 1.2 | 0.39–3.8 | 0.74 | |

| Tumor location (colon vs. rectum) | 0.83 | 0.43–1.6 | 0.58 | 0.79 | 0.34–1.8 | 0.59 | |

| Post-operative complications (no vs. yes) | 1.8 | 0.88–3.8 | 0.1 | 2.4 | 0.98–6.1 | 0.05 | |

| pT class (0–1 vs. 2–4) | 2.6 | 1–6.8 | 0.04 | 3.2 | 0.76–14 | 0.11 | |

| Tumor size (<2 vs. ≥2 cm) | 4.1 | 0.96–18 | 0.057 | 1.50E+08 | 0–Inf | >0.99 | |

CI, confidence interval; Inf, infinity; LND, lymph node dissection; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PSM, propensity score matching.

PSM was then carried out at a ratio of 1:2 (D2, n=88; D3, n=154) to compare clinical characteristics and pathologic variates of LND subsets. Aside from harvested lymph nodes (mean ± SD: 22.9±10.6 vs. 19.3±8.3; P=0.001), univariate analysis indicated that clinical and pathologic features of the two groups were essentially similar (Tables 1,2). After PSM, D3 LND (HR =2.3; 95% CI: 1.0–5.1; P=0.044) again was shown to be independently predictive of OS (HR =2.3; 95% CI: 1.0–5.1; P=0.04), along with age <70 years (HR =2.9; 95% CI: 1.4–28; P=0.01) and no family history of cancer (HR =0.36; 95% CI: 0.15–0.86; P=0.02) (Table 3). OS was still significantly better in the D3 (vs. D2) group (92.9% vs. 84.1%; P=0.036) (Figure 3C), with no statistical difference in RFS (95.5% vs. 94.3%; P=0.639) (Figure 3D).

Although multivariate analysis before and after matching failed to establish a clear correlation between RFS with D3 LND, postoperative RFS and lymph node metastasis displayed a significant association before PSM (HR =4.3; 95% CI: 2.1–8.6; P<0.001). Furthermore, intraoperative blood loss >100 mL was identified as a significant factor in postoperative RFS (before PSM: HR =2.6, 95% CI: 1–6.6, P=0.047; after PSM: HR =9.1, 95% CI: 1.9–45, P=0.006) (Table 4). In each group, the overall recurrence rate was 7.4%. There was no significant difference in recurrence rate between the two groups before and after matching (Table 5).

Table 4

| Variables | PFS before PSM | PFS after PSM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | ||

| LND (D3 vs. D2) | 0.51 | 0.19–1.4 | 0.18 | 0.97 | 0.28–3.4 | 0.96 | |

| Age (<70 vs. ≥70 years) | 1.8 | 0.88–3.5 | 0.11 | 4 | 0.8–20 | 0.092 | |

| Tumor location (colon vs. rectum) | 1.6 | 0.82–3.1 | 0.17 | 2 | 0.53–7.5 | 0.31 | |

| CEA (<2 vs. ≥2 ng/mL) | 1.9 | 0.85–4.1 | 0.12 | 1.5 | 0.42–5.3 | 0.53 | |

| Operative method (laparoscopic vs. open) | 1.3 | 0.4–4.4 | 0.64 | 0.81 | 0.12–5.7 | 0.83 | |

| Operative blood loss (≥100 vs. <100 mL) | 2.6 | 1–6.6 | 0.047 | 9.1 | 1.9–45 | 0.0065 | |

| Tumor size (<2 vs. ≥2 cm) | 2.1 | 0.72–5.9 | 0.18 | 2 | 0.23–18 | 0.52 | |

| Gross type (protruding vs. infiltrate or ulcerative) | 1.8 | 0.82–4.1 | 0.14 | 4.4 | 0.51–38 | 0.18 | |

| Lymphatic invasion (no vs. yes) | 1.2 | 0.59–2.5 | 0.6 | 3.4 | 0.74–16 | 0.12 | |

| Histology type (Well vs. Mod, Poor, Sig, Muc) | 1.1 | 0.52–2.3 | 0.81 | 0.62 | 0.11–3.6 | 0.59 | |

| Nodal metastasis (no vs. yes) | 4.3 | 2.1–8.6 | 0.000037 | 2.9 | 0.75–11 | 0.12 | |

Well, well-differentiated adenocarcinoma; Mod, moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma; Poor, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma; Muc, mucinous carcinoma; Sig, signet-ring carcinoma; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CI, confidence interval; LND, lymph node dissection; HR, hazard ratio; N.S., not significant; SD, standard deviation; PSM, propensity score matching; RFS, relapse-free survival.

Table 5

| Before PSM | After PSM | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=524) | D2 LND (n=99) | D3 LND (n=425) | P value | Total (n=242) | D2 LND (n=88) | D3 LND (n=154) | P value | ||

| Total metastasis | 39 (7.4) | 5 (5.1) | 34 (8.0) | N.S. | 12 (5.0) | 5 (5.7) | 7 (4.5) | N.S. | |

| Liver | 16 (3.1) | 2 (2.0) | 14 (3.3) | N.S. | 5 (2.1) | 2 (2.3) | 3 (1.9) | N.S. | |

| Lung | 19 (3.6) | 2 (2.0) | 17 (4.0) | N.S. | 4 (1.7) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (1.3) | N.S. | |

| Lymph node | 5 (1.0) | 2 (2.0) | 3 (0.7) | N.S. | 3 (1.2) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (0.6) | N.S. | |

| Peritoneum | 4 (0.8) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (0.7) | N.S. | 2 (0.8) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | N.S. | |

| Local recurrence | 5 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 4 (0.9) | N.S. | 3 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (1.3) | N.S. | |

| Bone | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | N.S. | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.3) | N.S. | |

| Brain | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | N.S. | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N.S. | |

| Adrenal gland | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N.S. | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N.S. | |

| Mediastinum | 2 (0.4) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.2) | N.S. | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | N.S. | |

Data are presented as n (%). LND, lymph node dissection; N.S., not significant; PSM, propensity score matching.

Discussion

Present study findings indicate a significant difference in OS for D2 and D3 LND subsets of resected cT2N0 CRC, with similar RFS. In Japan, the extent of LND depends on CRC staging, aiming to strike an appropriate balance between aggressive surgery and cure rate (6). The standard surgical approach to CRC in Western countries has become complete mesenteric resection (CME), with central vessel ligation (CVL). The key point of CME/CVL is to mobilize the colon along the embryological and anatomical planes to obtain a negative circumferential margin and ligation the root of the primary tumor-supplying artery for resection of an adequate mesentery. The Japanese D3 resection philosophy emphasizes the dissection of lymph nodes, including those at the root of the artery (7), but both strategies embody comparable principles and do provide good oncologic outcomes (8).

A previous study of ours has determined better survival outcomes for D3 (vs. D2) LND in patients with pT2 CRC (3). However, all treatment strategies were decided preoperatively, based on clinical tumor assessments, which do not always agree with pathologic diagnoses (9,10). In another multicenter retrospective study, long-term outcomes did not differ for D2 and D3 LND groups of surgically treated patients with cT2N0 CRC. However, PSM was lacking, perhaps introducing bias through differing backgrounds of grouped subjects (11).

It has been reported recently that CME in conjunction with central lymph node resection is analogous to D3 LND and may heighten the risk of vascular damage (compared with D2 LND) during laparoscopic surgery for right-sided colon cancer (12). However, our efforts have documented relatively shorter operative time, less intraoperative blood loss, fewer postoperative complications, and a briefer average hospital stay (2.7 days) for D3 (vs. D2) LND. The reason for above contradictory results is likely the greater control over quality of surgery ascribed to a single-center (rather than multicenter) environment. We also included rectal cancer in our analysis. Unlike right hemicolectomy, only one inferior mesenteric artery must be addressed during rectal resections, and fewer vascular variations are entailed.

In practice, D2 LND for rectal cancer involves a lengthy distance from root of inferior mesenteric artery; and superior rectal artery must be dissected once the left colonic artery is preserved. This will likely prolong operative time, increasing the risk of mesangial hemorrhage and surgical complications (13). Qualification examinations of the Japanese Society of Endoscopic Surgery therefore rely on D3 LND operative videos depicting inferior mesenteric artery dissection. With respect to rectal cancer, D3 LND is simpler and safer than D2 LND and more amenable to standardization, making it easy for young surgeons to master (2).

It should be noted that despite cT2N0 status as a study requirement, nodal metastases were detected in 22.2–24.9% of subjects postoperatively, with only 31.3–42.1% of cT2 cases ultimately confirmed as pT2. However, these outcomes are not inconsistent with those of past clinical studies (11,12). Although endoscopic ultrasound has been widely used recently to screen for early colon cancer (14), greatly improving diagnostic accuracy, enhancing the preoperative imaging precision of advanced CRC is an important future endeavor.

European, American, and Japanese guidelines for treatment of CRC all stipulate the harvesting of at least 12 lymph nodes for accurate staging (1). According to our data, more lymph nodes were harvested in the D3 (vs. D2) LND group (22.6 vs. 19.4). Still, both groups readily surpassed the 12-node minimum. Surgeons in Japan regularly collect lymph nodes immediately after specimens are isolated. In general, surgical and LND techniques alike are executed in mature and reliable fashion.

Based on aggregated data from the National JSCCR CRC Registry in Japan, ~1% of previously reported pT2 tumors exhibit spread to apical lymph nodes (2). The routine use of adjuvant chemotherapy, administered for 6 months after surgery in instances of nodal metastasis, may explain RFS similarities displayed by our D2 and D3 LND groups. In addition, the tumor cells of patients with CRC are heterogeneous, and the tumor cells of different patients have differences in biological behavior and response to treatment. For some patients, D3 LND can better target the characteristics of their tumor cells, thus affecting OS; But for RFS, this difference may be masked and appear as no difference, since the recurrence of tumor cells is affected by a variety of complex factors.

It has been reported that the prognosis of advanced colon cancer bears a relation to tumor location (15). We found no significant difference in RFS rates of D2 and D3 LND groups stratified by colonic or rectal location (P=0.110 and P=0.645, respectively). However, there was a significant difference in terms of OS (P=0.011 and P=0.05, respectively) (dates not shown).

D3 LND is more extensive, and if it can more effectively remove tumor cells and potentially metastatic lymph nodes and other tissues during D3 LND, it may reduce the risk of death due to tumor residue or metastasis, thereby prolonging OS.

Another interesting discovery was the identification of intraoperative bleeding as an independent risk factor for postoperative recurrence. Typically, vascular root ligation during D3 LND enables complete mesenteric resection and reduces associated bleeding (8,16). In D2 LND group, the mesenteric excision was not performed at the root of blood vessels, so it was easy to damage the vascular branches and cause bleeding. This could also explain why the D2 LND group had more bleeding. On the other hand, bleeding may obscure levels of surgical dissection, and intraoperative mesenteric incisions may cause spread or leave residual tumor behind, creating a high risk of postoperative recurrence.

Certain limitations of our study must be acknowledged. First, this was a single-center retrospective study, subject to selection bias. Another issue is the unreliability of clinically determined preoperative tumor and lymph node status. Presently, there is a need for prospective, randomized, and controlled clinical studies to evaluate the prognostic impact of D3 LND on patients with cT2N0 CRC.

Conclusions

Compared with D2 LND procedures, D3 LND improves perioperative outcomes and OS in patients with cT2N0 CRC. Accurate preoperative imaging diagnostics are critical for proper surgical management for cT2N0 CRC.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-2024-980/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-2024-980/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-2024-980/prf

Funding: This study was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-2024-980/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The institution’s Ethics Committee of Saitama Medical University International Medical Center approved our study (Ethics Board Registration No. 19-006). All subjects granted written informed consent preoperatively.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, et al. Colon Cancer, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021;19:329-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hashiguchi Y, Muro K, Saito Y, et al. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2019 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2020;25:1-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Song B, Chen Y, et al. D3 lymph node dissection improves the survival outcome in patients with pT2 colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 2023;38:30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Komono A, Shida D, Iinuma G, et al. Preoperative T staging of colon cancer using CT colonography with multiplanar reconstruction: new diagnostic criteria based on "bordering vessels". Int J Colorectal Dis 2019;34:641-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang LM, Hirano YM, Ishii TM, et al. The role of apical lymph node metastasis in right colon cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 2020;35:1887-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Japanese Classification of Colorectal, Appendiceal, and Anal Carcinoma: the 3d English Edition Secondary Publication. J Anus Rectum Colon 2019;3:175-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Søndenaa K, Quirke P, Hohenberger W, et al. The rationale behind complete mesocolic excision (CME) and a central vascular ligation for colon cancer in open and laparoscopic surgery: proceedings of a consensus conference. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014;29:419-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi H, West NP, Takahashi K, et al. Quality of surgery for stage III colon cancer: comparison between England, Germany, and Japan. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:S398-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kotake K, Kobayashi H, Asano M, et al. Influence of extent of lymph node dissection on survival for patients with pT2 colon cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 2015;30:813-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sjövall A, Blomqvist L, Egenvall M, et al. Accuracy of preoperative T and N staging in colon cancer--a national population-based study. Colorectal Dis 2016;18:73-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kojima T, Hino H, Shiomi A, et al. Long-term outcomes of D2 vs. D3 lymph node dissection for cT2N0M0 colorectal cancer: a multi institutional retrospective analysis. Int J Clin Oncol 2022;27:1717-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu L, Su X, He Z, et al. Short-term outcomes of complete mesocolic excision versus D2 dissection in patients undergoing laparoscopic colectomy for right colon cancer (RELARC): a randomised, controlled, phase 3, superiority trial. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:391-401. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Kondo H, Hirano Y, et al. Persistent Descending Mesocolon as a Key Risk Factor in Laparoscopic Colorectal Cancer Surgery. In Vivo 2020;34:807-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Catinean A, Balan GG, Mezei A, et al. Endoscopic Ultrasound Elastography in the Assessment of Rectal Tumors: How Well Does It Work in Clinical Practice? Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:1180. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Hirano Y, Ishii T, et al. Left colon as a novel high-risk factor for postoperative recurrence of stage II colon cancer. World J Surg Oncol 2020;18:54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hohenberger W, Weber K, Matzel K, et al. Standardized surgery for colonic cancer: complete mesocolic excision and central ligation--technical notes and outcome. Colorectal Dis 2009;11:354-64; discussion 364-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]