Systemic therapy for unresectable, mixed hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: treatment of a rare malignancy

Introduction

Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (HCC-CC) represents a small percentage (0.4–4.7%) of primary hepatic malignancies (1-3). Given the rarity of this disease, there are no clear treatment guidelines for advanced HCC-CC. The World Health Organization defines this malignancy as a tumor unequivocally admixed with both hepatocellular and CC (3). Surgical resection is the mainstay curative option; however, higher recurrence rates and shorter disease-free survival in HCC-CC have been reported compared to each separate malignancy (2,4-6). Liver transplantation appears to have poorer survival for combined HCC-CC in relation to HCC alone, although results are conflicting (2,7,8). Systemic therapy experience is limited to small case reports with regimens including sorafenib, doxorubicin + cisplatin, gemcitabine + cisplatin, fluorouracil monotherapy, and fluorouracil + oxaliplatin (9,10). With our case series, we aim to add to the existing knowledge with our institutional experience.

Methods

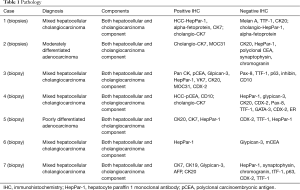

Our hepatobiliary database was reviewed during a 5-year time frame [2009–2014] for patients treated as mixed HCC-CC based on patient presentation, radiologic review, and multidisciplinary discussion. Of the 27 patients initially identified, seven were found to be independently confirmed by radiographic review as mixed HCC-CC and pathologically confirmed independently as either having a mixed HCC-CC diagnosis or having adenocarcinoma with both HCC and CC features. Pathologic features of these seven cases are listed in detail in Table 1. Similar to other reports, immunohistochemical (IHC) features identified for HCC were hepatocyte paraffin 1 monoclonal antibody (HepPar-1), polyclonal carcinoembryonic antigen (pCEA), and CD10 with CC features of cytokeratin 7 (CK7), cytokeratin 19 (CK19), MOC31 (1,2).

Full table

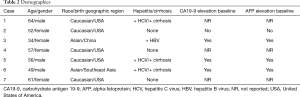

Data collection points included baseline demographics (age, gender, race, birth geographic region), relevant medical history such as hepatitis B or C (HBV or HCV) or cirrhosis, diagnosis date, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) at baseline; alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) at baseline; first-line therapy, localized therapy if utilized, second-line therapy, progression date, and death date or last follow-up. Outcomes reported were disease control rate first scan result on first-line or second-line treatment, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). Response was determined at first radiographic reimaging and was classified as disease-control (complete response + partial response + stable disease) or progression. Progression included patients who discontinued therapy due to toxicity. PFS was defined from the start of therapy to radiographic progression/toxicity withdraw or last follow-up, and OS was defined from the diagnosis date to date of death or last follow-up. Descriptive statistics were used with continuous variables described using median or mean, and range with categorical data summarized using frequencies and percentages.

Results

Individual patient details and outcomes are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Mean age was 53-year-old (range, 34–64 years) with most (57%) patients being female. A total of 57% had HBV or HCV with 42% having cirrhosis. When reported, CA19-9 and AFP were elevated at baseline in most cases. Regimens used in first-line were sorafenib (3 patients), gemcitabine + bevacizumab (2 patients), gemcitabine alone (1 patient), and gemcitabine plus cisplatin (1 patient). Seventy-one percent had progressive disease at first reimaging. Disease control was seen in two patients; one patient received gemcitabine plus platinum and one patient received gemcitabine + bevacizumab. All first-line sorafenib patients progressed at first radiographic evaluation. Front-line treatment only showed a median PFS of 3.4 months (range, 2.3–7 months).

Full table

Full table

Three patients went on to receive second-line therapy after progression and showed a median PFS of 6.5 months (range, 3.5–8.5 months). Regimens given second-line were gemcitabine + oxaliplatin (1 patient), gemcitabine + oxaliplatin + bevacizumab (1 patient), and fluorouracil + leucovorin + irinotecan (FOLFIRI) (1 patient). The two patients who receive gemcitabine + oxaliplatin with or without bevacizumab had disease control on first-scan. The patient that received FOLFIRI in the second-line had progression on first-scan. Of note, all patients who received a platinum (cisplatin or oxaliplatin) in combination with gemcitabine during their disease showed disease control with this regimen regardless of timing of therapy. These three patients had an impressive median OS of 17.5 months. The median OS of the entire cohort was 8.3 months (range, 3.3–32.8 months). Of note, our patient that had a prolonged survival (32.8 months) received localized intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) after first-line disease control with gemcitabine + cisplatin.

Discussion

Our case review confirms the rarity of combined HCC-CC and the issues that surround its diagnosis with only 7 out of 27 patients having both radiographic and pathologically confirmation after initial multidisciplinary review. Baseline clinical characteristics for combined HCC-CC have been conflicting and appear dependent on the geographic location (1,2). Our case series showed overlapping characteristics for both individual malignancies: elevation in CA19-9, AFP, cirrhosis, and hepatitis history; however our limited size and diverse patient geographic distribution makes it difficult to determine which are more prominent for this mixed tumor type.

Similar to the poor outcomes seen in HCC-CC with surgical resection and transplantation, systemic therapy appears to only minimally impact survival (1,2,5-8). Our case series demonstrates a median PFS of 3.4 months with front-line therapy and a median OS of 8.3 months. Sorafenib, FDA approved for front-line treatment of advanced HCC, has a median PFS and OS of 5.5 and 10.7 months, respectively (11). Additionally, in CC, gemcitabine plus cisplatin in the front-line setting has a median PFS of 8 months and median OS of 11.7 months based on the phase III ABC-02 study (12). Our case series indicated poorer outcomes when HCC-CC was treated similarly to these two separate malignancies.

Rare malignancies such as HCC-CC often rely on case reports, anecdotal experience, and extrapolating from more common malignancies in order to provide a guide for rational treatment decision-making. Although our case series carries limitations, gemcitabine + platinum (GP) with or without bevacizumab showed disease control in all patients (3 patients) that received this treatment in the first or second-line setting. Patients with advanced combined HCC-CC disease that are deemed unresectable need viable treatment options. Our small case series suggests a regimen that may have efficacy in this difficult disease and warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by Institutional Review Board of U.T. M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (PA11-1209) and a waiver of consent was granted due to patients lost to follow-up, no longer at the institution, or expired.

References

- Maximin S, Ganeshan DM, Shanbhogue AK, et al. Current update on combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. Eur J Radiol Open 2014;1:40-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Connor K, Walsh JC, Schaeffer DF. Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (cHCC-CC): a distinct entity. Ann Hepatol 2014;13:317-22. [PubMed]

- Theise ND, Nakashima O, Park YN, et al. Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. In: Bosman FT, World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer. World Health Organization classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press, 2010.

- Yano Y, Yamamoto J, Kosuge T, et al. Combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 26 resected cases. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2003;33:283-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee SD, Park SJ, Han SS, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma after surgery. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2014;13:594-601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim SH, Park YN, Lim JH, et al. Characteristics of combined hepatocelluar-cholangiocarcinoma and comparison with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2014;40:976-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vilchez V, Shah MB, Daily MF, et al. Long-term outcome of patients undergoing liver transplantation for mixed hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma: an analysis of the UNOS database. HPB (Oxford) 2016;18:29-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park YH, Hwang S, Ahn CS, et al. Long-term outcome of liver transplantation for combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Transplant Proc 2013;45:3038-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim GM, Jeung HC, Kim D, et al. A case of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma with favorable response to systemic chemotherapy. Cancer Res Treat 2010;42:235-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chi M, Mikhitarian K, Shi C, et al. Management of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: a case report and literature review. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2012;5:199-202. [PubMed]

- Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008;359:378-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1273-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]