|

Original Article

Survival of metastatic gastric cancer: Significance of age, sex

and race/ethnicity

Dongyun Yang1*, Andrew Hendifar2*, Cosima Lenz1, Kayo Togawa1, Felicitas Lenz2, Georg Lurje2, Alexandra Pohl2, Thomas Winder2, Yan Ning2, Susan Groshen1, Heinz-Josef Lenz1,2

1Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California/Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA; 2Division of Medical Oncology, Sharon Carpenter Laboratory, University of Southern California/Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA

* Both authors contributed equally to this work.

This work was funded by the NIH grant P30 CA 14089, supported by the San Pedro Guild and the Dhont Foundation.

Corresponding to: Heinz-Josef Lenz, MD, FACP. Sharon A. Carpenter Laboratory, Division of Medical Oncology, University of Southern California, Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Keck School of Medicine, 1441 Eastlake Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90033. Tel: +1-323-865-3967, Fax: +1-323-865-0061. Email: lenz@usc.edu.

|

|

Abstract

Background: Despite the success of modern chemotherapy in the treatment of large bowel cancers, patients with metastatic gastric cancer continue to have a dismal outcome. Identifying predictive and prognostic markers is an important step to improving current treatment approaches and extending survival.

Methods: Extracting data from the US NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries, we compared overall survival for patients with metastatic gastric cancer by gender, age, and ethnicity using Cox proportional hazards models. 13,840 patients (≥ 18 years) were identified from 1988-2004. Males and females were categorized by age grouping and ethnicity.

Results: 19% of Hispanic patients were diagnosed < 45 years of age as compared to 5.5% of Caucasians. Caucasian patients and men were more likely to be diagnosed with tumors in the gastric cardia (P<0.001). In our survival analysis, we found that women had a lower risk of dying as compared to men (P<0.001). Overall survival diminished with age (P<0.001). The median overall survival was 6 months in patients of ≤ 44 years old as compared to 3 months in patients 75 years and older. Gender differences in overall survival significantly varied by race and tumor grade/differentiation (P for interaction = 0.003 and 0.005, respectively).

Conclusion: This is the largest study of metastatic gastric cancer patients from the SEER registry to show that age, gender, and tumor location are significant independent prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic gastric cancer.

Key words

gastric cancer, gender, age, ethnicity, survival

J Gastrointest Oncol 2011; 2: 77-84. DOI: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2010.025

|

|

Introduction

Although its incidence and mortality has declined over the last half-century, gastric cancer remains the fourth

most common cancer and the second most frequent cause

of cancer death in the world ( 1, 2). The American Cancer

Society estimates that in 2008, there were 21,500 new cases

of gastric cancer and 10,880 deaths in the United States

( 3). As gastric cancer incidence declines, the frequency

of prox imal gastric and gastroesophageal junctional

adenocarcinomas continues to rise and has become a

significant clinical challenge ( 4, 5). There is substantial

geographic variation in the incidence and mortality of

gastric cancer, with the highest rates in East Asia and the

lowest in North America ( 2). H. pylori infection, dietary

factors, and smoking patterns may contribute to these

disparities ( 6-9). The survival rates for gastric cancer are among the worst of any solid tumor. Despite the success of modern

chemotherapy in the treatment of large bowel cancers, the

5-year survival of patients with advanced gastric cancer is

3.1% ( 1, 4). The role of surgery is also limited as only 23%

of stage IV gastric cancer patients receiving a palliative

gastrectomy are alive one year after surgery ( 4). Progress

was recently made as treating Her-2-Neu (H2N) overexpressing

gastric cancers with Traztuzumab was found to

significantly improve survival ( 10). Identifying additional

predictive and prognostic markers is an important step to

improving current treatment approaches and extending

survival. Two distinct histologic types of gastric cancer, the

“intestinal type” and “diffuse type”, have been described

( 11). The diffuse type of gastric cancer is undifferentiated

and characterized by the loss of E-cadherin expression; an

adhesion protein that helps maintains cellular organization

( 12). The well differentiated intestinal type is sporadic

and highly associated with environmental exposures,

especially H. pylori infection ( 13). There are also biologic

differences between these subtypes of gastric cancer that

may guide treatment approaches. H2N is over expressed

more often in the intestinal vs the diffuse type, 30% vs 6%

in one study ( 14). The Beta-catenin/Wnt signaling pathway

is also recognized to play a large role in the molecular

carcinogenesis of the intestinal type cancer ( 15). Despite the genetic heterogeneity of gastric cancer,

several biological determinants of risk and prognosis have

been identified. Genetic polymorphisms of cytokines

released with “oxidative stress” such as IL-Iβ, IL-10, and

TNF-A have been associated with increased gastric cancer

risk ( 16-18). Over expression of the oncogenes, tie-1, CMET

and AKT have been found to confer a poor prognosis in

both subtypes ( 19-21). Tumor expression of the isoenzyme

COX-2 is an independent prognostic factor for gastric

cancer survival ( 22). This benefit may be mediated by

a reduction in lymphangiogenesis, another correlate of

prognosis ( 22, 23). Recently Her-2/Neu over expression, an

important predictive and prognostic factor in breast cancer

has been independently associated with a poor prognosis in

gastric cancer ( 24, 25). The prognostic significance of age, gender, and ethnicity

in metastatic gastric cancer is unclear. The prevailing

belief that young patients with gastric cancer have a more

aggressive disease has been recently called into question

( 26, 27). Several prospective and population studies since

1996 have consistently shown that age is not a prognostic

factor for survival, despite the higher prevalence of “diffuse

type” cancer which typically has a worse outcome ( 28, 29).

However, according to a recent population-based study of

gastric cancer, a significant impact of age on survival was found in patients with stage IV disease ( 30). As compared to women, men are twice as likely to

develop and die from gastric cancer, in the US ( 1). Although

this may represent varying environmental exposures

between genders, studies demonstrate that menstrual

factors such as age of menopause and years of fertility are

associated with gastric cancer incidence ( 31). Interestingly,

woman may be more likely to have a “diffuse type histology”

( 32). There are also significant ethnic and racial differences

in gastric cancer incidence and survival. Asian patients

consistently have increased survival rates compared to

their western counterparts ( 33). Ethnic Asians living

in the US share this benefit which suggests that these

differences are not likely treatment related ( 34). Other

racial differences in the US are notable as the incidence

and mortality is 50% higher in African Americans than

Caucasians ( 35). Our study sought to evaluate the clinical correlates

of survival in metastatic gastric cancer. Specifically we

examined the inf luence of age, gender, ethnicity on

survival. We also explored the interactions between patient

characteristics and tumor histology, grade, size, and location

(cardia vs non-cardia).

|

|

Patients and methods

Data source

Adult patients with metastatic gastric cancer were identified

from the SEER registry 1988-2004 database, which collects

information on all new cases of cancer from 17 populationbased

registries covering approximately 26% of the US

population.

Study population

The disease was defined by the following International

Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O-2) codes:

C16.0-C16.9. We identified patients (n=15,360) who had

metastatic disease defined by SEER Extent of Disease code:

85. We restricted eligibility to adults (aged 18 years or

older) who were diagnosed with metastatic gastric cancer

(MGC) in 1988 and later (n=15,348); because the record of

extent of disease was not available for accurate staging prior

to 1988. We excluded cases (less than 10% of adult patients

with metastatic gastric cancer) who were diagnosed at death

certificate or autopsy, no follow-up records (survival time

code of 0 months), as well as lacking documentation on

race/ethnicity. A total of 13,840 MGC patients of 18 years

and older were included in the final sample for the current

analysis.

Variable definitions

Information on age at diagnosis, sex, race, and ethnicity,

marital status, treatment type, primary site, tumor grade

and differentiation, histology, tumor size, and lymph node

involvement, and overall survival were coded and available

in SEER database. The primary endpoint in this study was

overall survival that was defined as the months lapsing

from diagnosis to death. For the patients who were still

alive at last follow-up, overall survival was censored at the

date of last follow-up or December 31, 2004, whichever

came first.

Age. We chose the cut points for age groups based on the

previous studies (18-44, 45-54, 55-64, 65-74, and 75 and

older).

Ethnicity. Patients were divided into five ethnic groups,

“Caucasian” (Race/Ethnicity code, 1), “African American”

(Race/Ethnicity code, 2), “Asian” (Race/Ethnicity code,

4-97), “Hispanic” (Spanish/Hispanic Origin code, 1-8), and

Native American (Race/Ethnicity code, 3).

Primary site. According to the latest guidelines for

gastric cancer classificationa, the stomach is anatomically

delineated into the upper, middle, and lower thirds by

dividing the lesser and greater curvatures at two equidistant

points and joining these points. The sites were defined by

the following codes from ICD-O-2: Cardia, (C16.0), Body

(C16.1-2, C16.5-6), Lower (C16.3-4), and Overlapping

lesion of stomach (C16.8). For the ones that are not

specified, they were categorized together as Stomach, NOS

(C16.9).

Marital status. Subjects were categorized into “Not

married” (including never married, separated, divorced,

widowed, and unknowns) and “Married” (including

common law).

Treatment type. SEER variables, RX Summ-radiation

and RX summ-surg prim site were used to define treatment

types: “Surgery” for patients who had surgery (local

tumor destruction and excision, and gastrectomy) and/no

radiation, “Radiation therapy only” for patients who only

had radiation therapy, “Untreated” for patients who did

not have surgery nor radiation therapy, and “Unknown”.

Information on chemotherapy was not available in SEER.

Grade. Grade was defined by the following ICD-O-2

codes; well/moderately differentiated (Code 1-2), poorly

differentiated/undifferentiated (Code 3-4), and others

(Code 5-9).

Histological type. Histological types were defined by the

following ICD-O-3 codes: 8140- for adenocarcinoma, 8490

for Signet ring cell carcinoma, and the rest of the types were

categorized as ‘Others’.

The size of the primary tumor and the presence of

lymph node involvement were not of interest in the current analysis. Our cohort consisted entirely of patients with

metastatic disease.

Statistical analysis

Subjects were grouped by age to 18-44, 45-54, 55-64, 65-74,

and 75 and older. We stratified them by sex, race, marital

status, treatment type, grade, histological type, and primary

site. Descriptive statistics were calculated for categorical

variables using frequencies and proportions. Sex, race,

tumor grade, marital status, primary site, histological type,

and treatment type were independent variables. Differences

among age groups in each subgroup were evaluated using

the chi-square test.

We constructed Cox proportional hazards models to

examine the association between age and survival in men

and female separately. We compared survival across age

groups adjusting for potential confounders including

geographic region and year of diagnosis. By conducting

this ana lysis separately by gender, we were able to

determine pattern differences between genders. The Cox

proportional hazards model included year of diagnosis and

participating SEER registry site as stratification variables.

Marital status, treatment, primary site, histology, tumor

grade and differentiation, size of primary tumor, and lymph

node involvement were used as covariates. Hazard Ratios

(HRs) and 95% confidence intervals were generated, with

hazard ratios less than 1.0 indicating survival benefit (or

reduced mortality). Pairwise interactions (age and sex, age

and race, and sex and race) were checked using stratified

models and were tested by comparing corresponding

likelihood ratio statistics between the baseline and

nested Cox proportional hazards models that included

the multiplicative product terms ( 36). Departure of the

proportional hazard assumption of Cox models will be

examined graphically such as log-log survival curves or

smoothed plots of weighted Schoenfeld residuals ( 37) and

by including a time-dependent component individually for

each predictor. All analyses were conducted using P<0.05 as the

significance level and statistical analyses were performed

with the use of SAS software (version 9.1; SAS Institute,

Cary, NC).

|

|

Results

Patient baseline characteristics

The final cohort for analysis consisted of 13,840 patients,

8710 men (63%), and 5130 women (37%). Their age

distribution is as follows: 1,207 (9%) aged 18−44; 1,698

(12%) aged 45−54; 2,701 (20%) aged 55−64; 3,901 (28%)

aged 65−74; and 4,333 (31%) aged 75 years and older. The median age was 68 years (range: 18−104). 60% of the MGC

cohort were White, 13% African American, 13% Asian, 14 %

Hispanic, and 1% Native American. Tumor characteristics

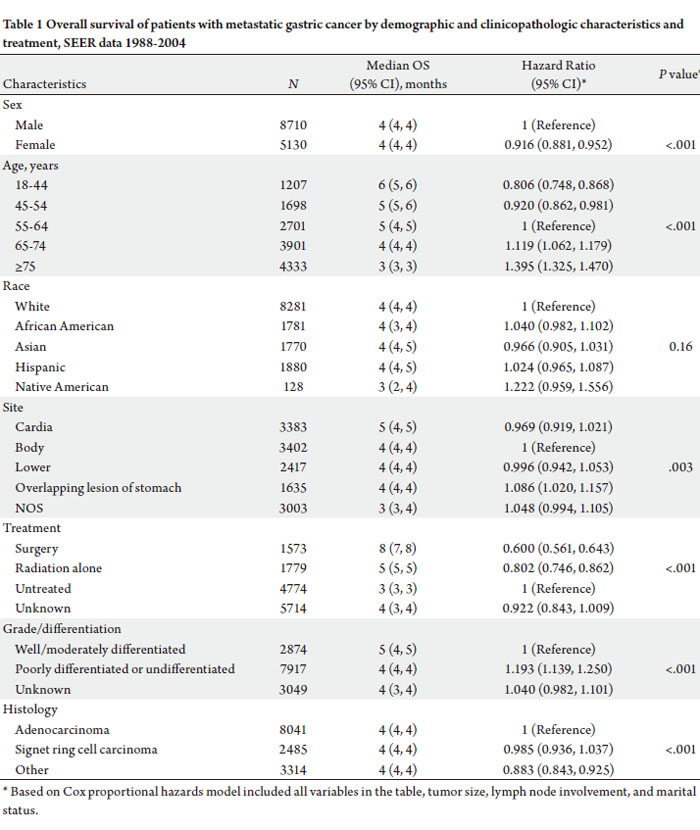

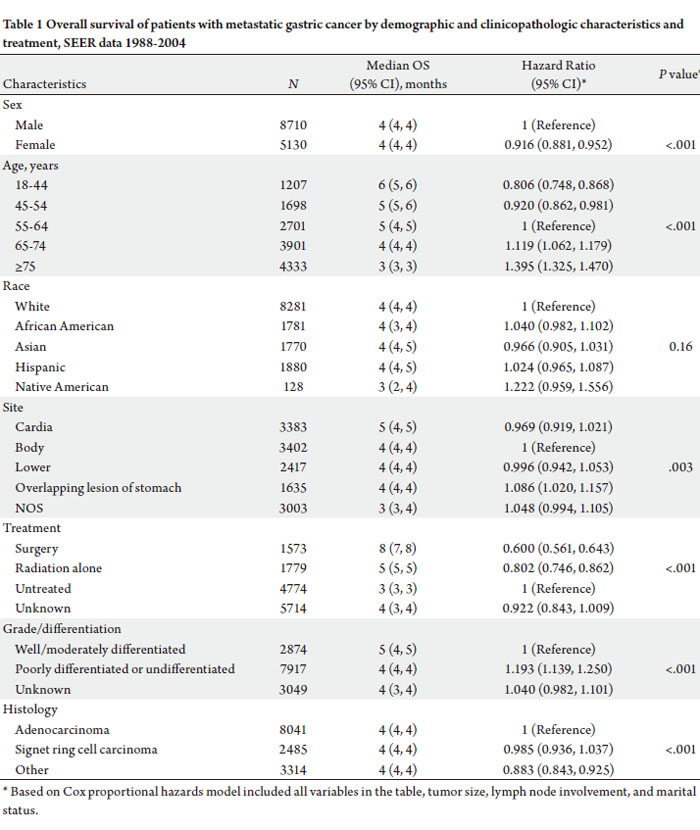

and treatment received are shown in Table 1.

Age and ethnicity in MGC

5.5 % of Whites with MGC were between 18-44 years of

ages as compared to 10% of African Americans, 11% of

Asians, and 19% of Hispanic patients. 36% of White gastric

cancer patients were diagnosed over 75 years of age; 29% of Asian, 27% of AA, and 20% of Hispanic.

Tumor location: cardia vs non-cardia

The incidence of cardia and non-cardia tumors varied

significantly depending on gender and ethnic background.

30% of men and 14% of women had gastric ca arising

from the cardia. The incidence of cardia cancers also

varied significantly across ethnicities. 32% of Whites had

cardia primaries, 13% of AA’s, 11% of Asians, and 14% of

Hispanics.

Survival analysis

The median overall survival (OS) in patients with MGC

was only 4 months. The prognostic significance of several

clinical and tumor characteristics were limited as the

median OS varied little when stratified by sex, race, tumor

site, grade/ differentiation, and histology (Table 1).

However, age, use of local treatment, tumor differentiation,

and tumor site were found to have a clinically significant

effect. The youngest group of patients had an improved OS

when compared to their older counterparts (Table 1), as the

median OS for patients 44 years or younger was 6 months

compared to 3 months in patients 75 years or older. Survival

was significantly worse in every successive age decile.

Patients who had received any treatment had significantly

improved survival. Gastrectomy or local surgery had a

median OS of 8 months compared to a median OS of 3

months in patients who were not treated with surgery or

radiation [HR = 0.600 (0.561, 0.643)] (Table 1). Similarly,

patients receiving radiation treatment had a survival benefit

[HR = 0.802 (0.746, 0.862)].

Tumor characteristics had a significant impact on

survival. As expected, patients with poorly differentiated

tumors had a worse survival than those with moderately

or well differentiated tumors [HR 1.19, P

In multivariate analysis, sex, age, treatment, and tumor

characteristics were significantly associated with overall

survival. Females had lower risk of dying compared to males

(HR=0.916, 95%CI: 0.881−0.952) and mortality increased

with age at diagnosis (P<0.001, Table 1). There was no

significant difference in OS across race/ethnicity groups

(P=0.16, Table 1).

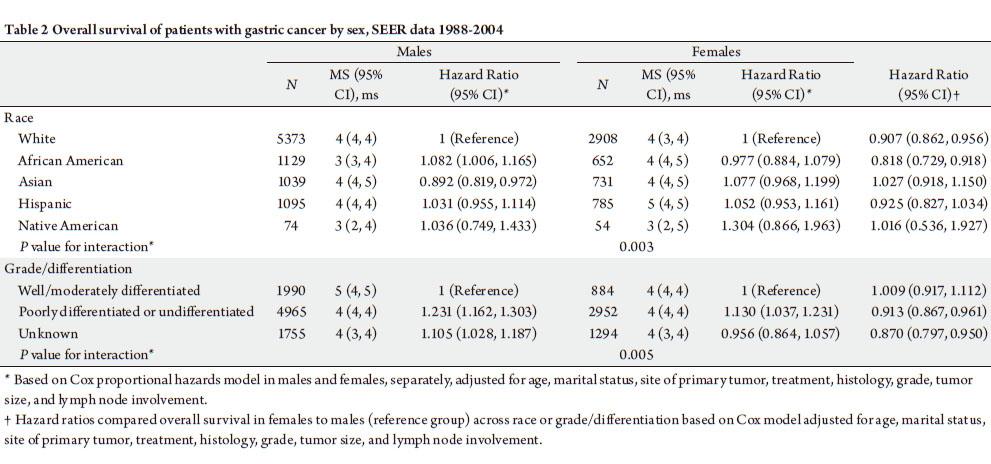

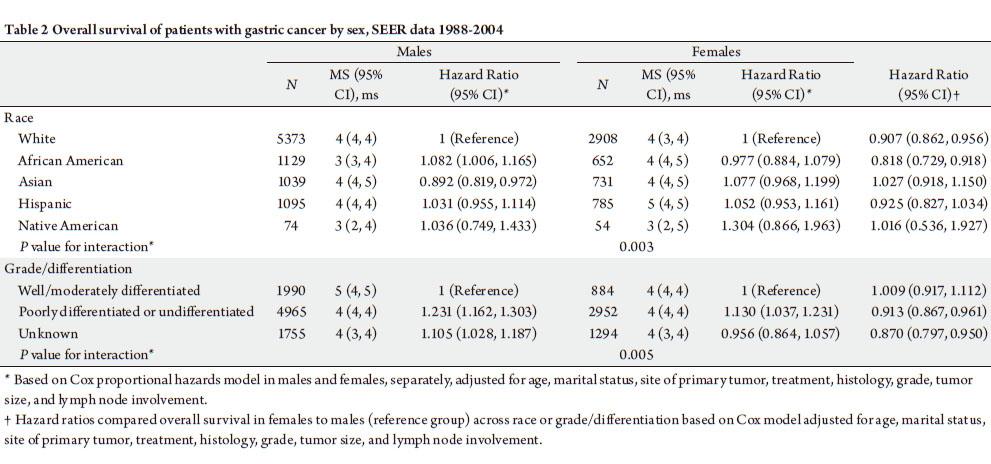

Sex, race, grade/differentiation and MGC

The effect of sex on OS was signif icantly varied by

race and tumor differentiation in patients with MGC

(Pfor interaction=0.003 and 0.005, respectively, Table 2).

White and African American woman had significantly lower risk of dying compared to their male counterparts. In

Asian, Hispanic, and Native American populations, men

and women had equivalent survival (Table 2.) Women also

had a significantly lower risk of dying compared to males

in patients whose tumors were poorly differentiated or

undifferentiated or had unknown tumor grade (Table 2).

|

|

Discussion

This cohort of metastatic gastric cancer patients from the

SEER database represents a wide cross-section of patients

with variable socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds. Our

analysis also included a robust variety of pathology and is

likely a more generalizable representation than can be found

in clinical trials or case series.

As expected, we found tumor characteristics such as

grade, differentiation, and histology were associated with

survival in advanced gastric cancer. Notably, there was a

survival advantage attributable to gastric cardia lesions

when compared to non-cardia lesions. This sur vival

advantage persisted after controlling for the increased

prevalence of cardia lesions in Caucasians and men.

Survival differences between cardia and non-cardia

lesions may reflect differences in pathogenesis and tumor

biology. H. pylori infection is recognized as a unique risk

factor for non-cardia lesions while gastroesophageal reflux

disease plays a role in the development of proximal lesions

( 38, 39). Interestingly, there is growing evidence that H2N

expression is variably expressed in proximal and distal

gastric cancer lesions ( 40). The proto-oncogene Her-2/neu

(H2N) is located on chromosome 17q21 and encodes a

transmembrane tyrosine kinase growth factor receptor

featuring substantial homology with the EGFR ( 41, 42).

Over-expression of the H2N protein has been identified

in from 10 to 34% of breast cancers and is associated with

a poor prognosis ( 43). Over-expression of H2N has been

reported in gastric and gastro-esophageal tumors ( 24).

Additionally, there are studies describing H2N as a poor

prognostic factor in gastric cancer ( 40). Further studies are

needed to investigate its role in the development of proximal

and distal gastric lesions. In addition to tumor characteristics, patient features,

such as age and sex, also had significant prognostic impact.

Ethnicity – often described in gastric cancer literature

as having a prominent prognostic role – had no effect

on survival. We could not confirm previous reports that

Asian and Hispanic patients with gastric cancer have an

improved outcome. We did find that a higher percentage

of Hispanic patients present at a younger age. 36% of our

Hispanic patients presented at ages less than 54 yo vs 16%

of white patients. These findings are consistent with a single institution study, which found that

Hispanics present at a younger age when

compared to other ethnicities ( 44). After adjusting for sex, race, marital

status , treatment type, primary site,

histology, the year of diagnosis and SEER

site, we found significant increased cancerspecific

mortality among men and older age

groups. The survival for our youngest age

group was 2 fold higher than the oldest age

group. Our findings do not confirm previous

reports that younger patients with metastatic

gastric cancer have poorer survival. Outside

of treatment with surgery, young age was

the best prognostic marker. We could not

address the role of systemic chemotherapy

on overall survival in the current study due

to lack of information in SEER. This likely

ref lects the higher rate of treatment we

found in the younger patients and unlikely

represents differences in tumor biology or

kinetics.

Consistent with previous reports, we

found that women with MGC lived longer

than men. We did not find any association

between gender disparities and age.

Women of every age group, pre-and postmenopausal,

had an equivalent survival

advantage. When examined more closely,

we found that this difference was limited to

African American and White patients. There

were no gender differences in the Hispanic

and Asian patients. These differences were

not attributable to the presence of cardia

or non-cardia lesions. Although there have

been no reports of variable expression of

H2N by gender, there are gender differences

in expression of estrogen receptor (ER)

and ER messenger RNA in gastric cancer

( 45). A possible explanation for the survival

advantages in women may be found in a

recent study addressing the interactions

between the estrogen receptor and her-

2neu receptor pathways in breast cancer

development and treatment response.

Hurtado and colleagues found her-2-neu up

regulation following the silencing of PAX-2

in cell lines treated with tamoxifen, which

suggests that tamoxifen-estrogen receptor

and estradiol-estrogen receptor complexes

inhibits transcription of Her-2-Neu via Pax-2 ( 46). Despite the clinical and genetic variability of advanced

gastric cancer, we were able to identify clinical correlates

for improved outcomes, which included gender and age. We

did not find an association between ethnicity and survival.

This is thought provoking as there are clear differences

in the age of presentation and the prevalence of cardiac

tumors. Hispanic patients were twice as likely to develop

gastric cancer at < 45 years old than Caucasians. Conversely

Caucasians were twice as likely to develop gastric cardia

lesions vs non-proximal cancers. Further research into

biological basis for these differences is warranted.

|

|

References

- Brenner H, Rothenbacher D, Arndt V. Epidemiology of stomach cancer.

Methods Mol Biol 2009;472:467-77.[LinkOut]

- Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence,

mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to

reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J

Clin Oncol 2006;24:2137-50.[LinkOut]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, et al. Cancer statistics,

2008. CA Cancer J Clin 2008;58:71-96.[LinkOut]

- Karpeh M, Kelsen D, Tepper J. Cancer of the stomach. In: DeVita

V, Hellman S, Rosenberg S, editors. Cancer Principles & Practice of

Oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincot, Williams & Wilkins; 2001. p.

1092-126.

- Devesa SS, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF Jr. Changing patterns in the incidence

of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer

1998;83:2049-53.[LinkOut]

- Kamangar F, Qiao Y, Blaser MJ, Sun XD, Katki H, Fan JH, et al.

Helicobacter pylori and oesophageal and gastric cancers in a prospective

study in China. Br J Cancer 2007;96:172-6.[LinkOut]

- Bertuccio P, Praud D, Chatenoud L, Lucenteforte E, Bosetti C, Pelucchi

C, et al. Dietary glycemic load and gastric cancer risk in Italy. Br J

Cancer 2009;100:558-61.[LinkOut]

- Abnet CC, Freedman ND, Kamangar F, Leitzmann M, Hollenbeck AR,

Schatzkin A. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of gastric

and oesophageal adenocarcinomas: results from a cohort study and a

meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2009;100:551-7.[LinkOut]

- Shikata K, Doi Y, Yonemoto K, Arima H, Ninomiya T, Kubo M, et

al. Population-based prospective study of the combined inf luence of

cigarette smoking and Helicobacter pylori infection on gastric cancer

incidence: the Hisayama Study. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168:1409-15.[LinkOut]

- Van Custem E, Kang Y, Chung H, Shen L, Sawaki A, Lordick F, et al.

Efficacy results from the ToGA trial: A phase III study of trastuzumab

added to standard chemotherapy (CT) in first-line human epidermal

growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive advanced gastric cancer

(GC) [abstract]. J Clin Oncol 2009;s27:LBA4509.

- Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse

and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1965;64:31-49.[LinkOut]

- Guilford P, Hopkins J, Harraway J, McLeod M, McLeod N, Harawira P,

et al. E-cadherin germline mutations in familial gastric cancer. Nature

1998;392:402-5.[LinkOut]

- Takenaka R, Okada H, Kato J, Makidono C, Hori S, Kawahara Y, et

al. Helicobacter pylori eradication reduced the incidence of gastric

cancer, especially of the intestinal type. Aliment Pharmacol Ther

2007;25:805-12.[LinkOut]

- Vergara R, Torrazza I, Castillo Fernandez O. Her-2/Neu overexpression

in gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;s27:e15679.

- Clements W, Wang J, Sarnaik A, Kim OJ, MacDonald J, Fenoglio-

Preiser C, et al. beta-Catenin mutation is a frequent cause of Wnt

pathway activation in gastric cancer. Cancer Res 2002;62:3503-6.[LinkOut]

- El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH, McColl KE, Bream JH, Young

HA, et al. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk

of gastric cancer. Nature 2000;404:398-402.[LinkOut]

- El-Omar EM, Rabkin CS, Gammon MD, Vaughan TL, Risch HA,

Schoenberg JB, et al. Increased risk of noncardia gastric cancer

associated with proinf lammatory cytokine gene polymorphisms.

Gastroenterology 2003;124:1193-201.[LinkOut]

- Gorouhi F, Islami F, Bahrami H, Kamangar F. Tumour-necrosis

factor-A polymorphisms and gastric cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Br J

Cancer 2008;98:1443-51.[LinkOut]

- Amemiya H, Kono K, Itakura J, Tang RF, Takahashi A, An FQ, et al.

c-Met expression in gastric cancer with liver metastasis. Oncology

2002;63:286-96.[LinkOut]

- Cinti C, Vindigni C, Zamparelli A, La Sala D, Epistolato MC, Marrelli

D, et al. Activated Akt as an indicator of prognosis in gastric cancer.

Virchows Arch 2008;453:449-55.[LinkOut]

- Lin WC, Li AF, Chi CW, Chung WW, Huang CL, Lui WY, et al. tie-1

protein tyrosine kinase: a novel independent prognostic marker for

gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res 1999;5:1745-51.[LinkOut]

- Mrena J, Wiksten JP, Thiel A, Kokkola A, Pohjola L, Lundin J, et al.

Cyclooxygenase-2 is an independent prognostic factor in gastric cancer

and its expression is regulated by the messenger RNA stability factor

HuR. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11:7362-8.[LinkOut]

- Iwata C, Kano MR, Komuro A, Oka M, Kiyono K, Johansson E, et al.

Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 suppresses lymph node metastasis via

reduction of lymphangiogenesis. Cancer Res 2007;67:10181-9.[LinkOut]

- Tanner M, Hollmén M, Junttila T, Kapanen A, Tommola S, Soini Y,

et al. Amplification of HER-2 in gastric carcinoma: association with

Topoisomerase IIalpha gene amplification, intestinal type, poor

prognosis and sensitivity to trastuzumab. Ann Oncol 2005;16:273-8.[LinkOut]

- Park DI, Yun JW, Park JH, Oh SJ, Kim HJ, Cho YK, et al. HER-2/neu

amplification is an independent prognostic factor in gastric cancer. Dig

Dis Sci 2006;51:1371-9.[LinkOut]

- Holburt E, Freedman SI. Gastric carcinoma in patients younger than

age 36 years. Cancer 1987;60:1395-9.[LinkOut]

- Wang JY, Hsieh JS, Huang CJ, Huang YS, Huang TJ. Clinicopathologic

study of advanced gastric cancer without serosal invasion in young and

old patients. J Surg Oncol 1996;63:36-40.[LinkOut]

- Lee JH, Ryu KW, Lee JS, Lee JR, Kim CG, Choi IJ, et al. Decisions for

extent of gastric surgery in gastric cancer patients: younger patients

require more attention than the elderly. J Surg Oncol 2007;95:485-90.[LinkOut]

- Tso PL, Bringaze WL 3rd, Dauterive AH, Correa P, Cohn I Jr. Gastric

carcinoma in the young. Cancer 1987;59:1362-5.[LinkOut]

- Al-Refaie WB, Pisters PW, Chang GJ. Gastric adenocarcinoma in

young patients: A population-based appraisal [abstract]. J Clin Oncol

2007;s25:4547.

- Freedman ND, Chow WH, Gao YT, Shu XO, Ji BT, Yang G, et al.

Menstrual and reproductive factors and gastric cancer risk in a large

prospective study of women. Gut 2007;56:1671-7.[LinkOut]

- Dicken BJ, Bigam DL, Cass C, Mackey JR, Joy AA, Hamilton SM.

Gastric adenocarcinoma: rev iew and considerations for future

directions. Ann Surg 2005;241:27-39.[LinkOut]

- Bollschweiler E, Boettcher K, Hoelscher AH, Sasako M, Kinoshita T,

Maruyama K, et al. Is the prognosis for Japanese and German patients

with gastric cancer really different? Cancer 1993;71:2918-25.[LinkOut]

- Theuer CP, Kurosaki T, Ziogas A, Butler J, Anton-Culver H. Asian

patients with gastric carcinoma in the United States exhibit unique

clinical features and superior overall and cancer specific survival rates.

Cancer 2000;89:1883-92.[LinkOut]

- Ries LA, Wingo PA, Miller DS, Howe HL, Weir HK, Rosenberg HM, et

al. The annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973-1997,

with a special section on colorectal cancer. Cancer 2000;88:2398-424.[LinkOut]

- Rothman K. Modern epidemiologyed. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-

Raven; 1998.

- Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Propor tiona l hazards tests and

diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 1994;81:512-26.[LinkOut]

- Lagergren J, Bergström R, Lindgren A, Ny rén O. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma.

N Engl J Med 1999;340:825-31.[LinkOut]

- Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and

Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies

nested within prospective cohorts. Gut 2001;49:347-53.[LinkOut]

- Ross JS, McKenna BJ. The HER-2/neu oncogene in tumors of the

gastrointestinal tract. Cancer Invest 2001;19:554-68.[LinkOut]

- Akiyama T, Sudo C, Ogawara H, Toyoshima K, Yamamoto T. The

product of the human c-erbB-2 gene: a 185-kilodalton glycoprotein

with tyrosine kinase activity. Science 1986;232:1644-6.[LinkOut]

- Coussens L, Yang-Feng TL, Liao YC, Chen E, Gray A, McGrath

J, et al. Tyrosine kinase receptor with extensive homology to EGF

receptor shares chromosomal location with neu oncogene. Science

1985;230:1132-9.[LinkOut]

- Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire

WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with

amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science 1987;235:177-82.[LinkOut]

- Yao JC, Tseng JF, Worah S, Hess KR, Mansfield PF, Crane CH, et al.

Clinicopathologic behavior of gastric adenocarcinoma in Hispanic

patients: analysis of a single institution's experience over 15 years. J Clin

Oncol 2005;23:3094-103.[LinkOut]

- Zhao XH, Gu SZ, Liu SX, Pan BR. Expression of estrogen receptor and

estrogen receptor messenger RNA in gastric carcinoma tissues. World J

Gastroenterol 2003;9:665-9.[LinkOut]

- Hurtado A, Holmes KA, Geistlinger TR, Hutcheson IR, Nicholson

RI, Brown M,et al. Regulation of ERBB2 by oestrogen receptor-PAX2

determines response to tamoxifen. Nature 2008;456:663-6.[LinkOut]

Cite this article as:

Yang D, Hendifar A, Lenz C, Togawa K, Lenz F, Lurje G, Pohl A, Winder T, Ning Y, Groshen S, Lenz H. Survival of metastatic gastric cancer: Significance of age, sex

and race/ethnicity. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;2(2):77-84. DOI:10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2010.025

|