|

Original Article

Increasing disparity in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality among African Americans and whites: A state’s experience

Noelle K LoConte1,2, Amy Williamson1, Arlene Gayle2, Jennifer Weiss2, Ticiana Leal1,2, Jeremy Cetnar1,2, Tabraiz Mohammed2, Amye Tevaarwerk1,2, Nathan Jones1

1University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center, Madison, WI; 2University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI

Corresponding to: Noelle LoConte, MD. University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics 600 Highland Ave, CSC K4/548, Madison, WI 53792. Tel: 608-265-5883; Fax: 608-265-5883. Email: Ns3@medicine.wisc.edu.

|

|

Abstract

Objectives: To measure disparities between African Americans and whites in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality rates between 1995-2006 in Wisconsin.

Methods: Cancer incidence data were obtained from the Wisconsin Cancer Reporting System. Cancer mortality data were accessed from the SEER. Trends in incidence and mortality rates were calculated and changes in relative disparity were measured using rate ratios.

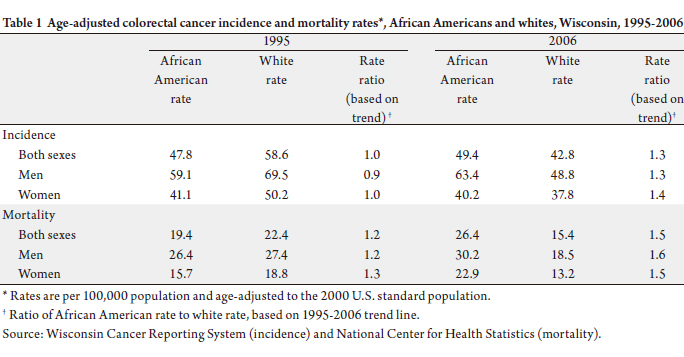

Results: The relative disparity in incidence grew from 1.0 in 1995 and 1.3 in 2006. The relative disparity in death rates for African Americans widened as well, from 1.2 to 1.5.

Conclusion: A persistent and widening colorectal cancer racial disparity exists.

Key words

colorectal cancer, epidemiology, disparities

J Gastrointest Oncol 2011; 2: 85-92. DOI: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2011.014

|

|

Introduction

Cancer health disparities, defined by the National Cancer

Institute (NCI) as “differences in the incidence, prevalence,

mortality, and burden of cancer and related adverse health

conditions that exist among specific population groups”

( 1), are an important and growing concern. Although

treatments for cancer are improving and cancer mortality

is decreasing, not all Americans benefit equally from these

successes ( 2). National organizations such as the NCI, US

Department of Health and Human Services, and American

Cancer Society have targeted the elimination of cancer

health disparities, as have many state comprehensive cancer

control plans ( 3). Disparities in colorectal cancer (CRC) are often highlighted as being a particular source of concern.

Nationwide CRC is the second leading cause of cancer

mortality and the fourth leading source of new cancer cases

( 4). African Americans experience higher CRC incidence

rates, leading some organizations to recommend screening

African Americans at age 45 ( 5). The most recent national

data from NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End

Results (SEER) program shows that from 2002 to 2006 the

CRC incidence rate among white males was 58.2 cases per

100,000, while among African American men, the rate was

68.4. There is a similar disparity in mortality nationally

(death rate among white men of 21.4 per 100,000, compared

to 31.4 per 100,000 among African American men) ( 6).

Although national incidence and mortality rates for CRC

have been decreasing in recent years, the decrease has not

been as pronounced among African Americans as it has

been in whites ( 7, 8). There is also evidence that African

Americans present with more advanced stage disease at

diagnosis, and at a younger age ( 7, 9-11). Other studies have

identified disproportionate survival differences by race,

despite equal treatment ( 10, 12-15). Some authors have

suggested that these differences may reflect variations in

tumor biology and genetics by race ( 7, 8, 16). Additional

causes of CRC disparities by race are thought to be multifactorial and include differences in socioeconomic status ( 8,

9), rates of obesity ( 17), screening rates ( 18), and health care

utilization ( 19), as well as a trend towards more right-sided

(proximal) tumors among African Americans ( 13, 20-24). The purpose of this study is to present trends in African

American/white disparities in CRC incidence and mortality

in Wisconsin. Monitoring trends in cancer incidence and

mortality is an important part of any coordinated state

plan to reduce disparities, providing critical information

to cancer prevention programs, clinicians, and policy

makers who seek to reduce the burden of cancer. While

there is evidence of trends in African American/white CRC

disparities at the national level, there are no such trend

data for Wisconsin, as previously published reports ( 25-28)

have combined several years of data in order to present data

for multiple ethnic groups. By filling these gaps, the paper

provides an example of state-level surveillance required for

CRC control.

|

|

Methods

Data sources

We obtained incidence data from the Wisconsin Cancer

Reporting System (WCRS) for the period 1995 to 2006,

the most recent year for which data were available. As

required by state law, cancer cases are reported to WCRS

by Wisconsin hospitals, clinics, and physician offices. All

invasive and noninvasive malignant tumors, except basal

and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin and in situ cancers

of the cervix uteri, are reportable to WCRS. Incidence rates

were age-adjusted using the 2000 US standard population

and calculated using NCI’s SEER*Stat software.

Mortality data used in this study reflect Wisconsin

resident death records from the Vital Records Section,

Wisconsin Department of Health Services. We accessed

mortality data from the National Center for Health

Statistics (NCHS) public use data file of Wisconsin deaths

covering the period 1995 to 2006. Population data used in

calculating cancer rates are obtained periodically by NCHS

from the Census Bureau; those used in this study were ageadjusted

to the 2000 US standard population. We used

SEER*Stat software to calculate mortality rates. We also

applied race categories used by NCHS (“White” and “Black

or African American”) ( 29). Stage of diagnosis was obtained from WCRS, which

codes cases based on SEER staging guidelines. Precise

American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging ( 30) is

not currently available from WCRS; cancers are described

as “localized” (invasive tumor that is confined to the organ

of origin), “regional” (tumor spread beyond the organ of

origin to adjacent organs or tissue by direct extension, or through the regional lymph nodes, or both, but appears

to have spread no further) or “distant” (tumor has spread

to parts of the body remove from the primary organ, or a

systemic malignancy) ( 28). Some cases are unstaged, due

to insufficient information. The stage data are not ageadjusted.

Analysis

The observed annual incidence and mortality rates were

plotted over the period 1995 to 2006 for all Wisconsin

residents, by race and gender. (Due to data variability

resulting from small populations, averages over three

years are presented in the figures below.) Using slopes and

intercepts derived from ordinary least squares regressions,

trend lines of the incidence and mortality data were then

plotted. The ratio of the African American rate to the

white rate (rate ratio) in 1995 and 2006, based on the

1995-2006 trend line, was calculated. This ratio constitutes

the measure of relative disparity ( 31), and was compared

between the beginning and the end of the period. Due to limited number of African American cases

in some years, we combined stage data in three-year

increments: 1995-1997, 1998-2000, 2001-2003, and

2004-2006. Due to the small number of distant cases among

African Americans (fewer than 30 per year in the state),

only localized and regional disease were analyzed.

|

|

Results

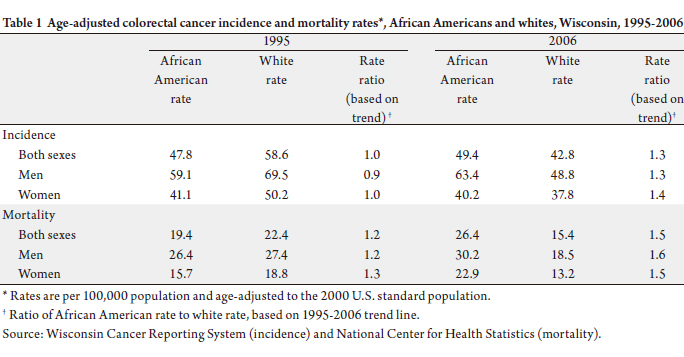

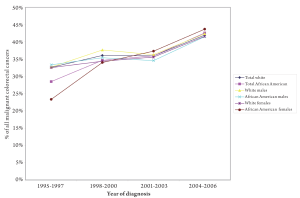

Stage at diagnosis

Among white and African American men and women of

both races, the percentage of malignant CRC cases which

were localized at diagnosis increased over the period

1995-2006, with the percentage for all groups reaching

nearly 40% in 2004-2006 (Figure 1). In contrast, the

percentage of cases which involved regional tumors at

diagnosis decreased for all groups, falling to approximately

30% of all cases in 2004-2006 (Figure 2). There were 20

or fewer cases of distant disease annually among African

Americans in Wisconsin (45 in 1995-1997, 52 in 1998-2000,

61 in 2001-2003, and 81 in 2004-2006). Due to the small

number of distant cases over these periods, it is difficult to

draw conclusions about the trends in these advanced cases

relative to earlier staged CRC among African Americans,

however, the number of distant cases increased over time.

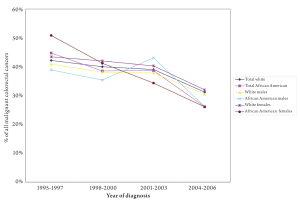

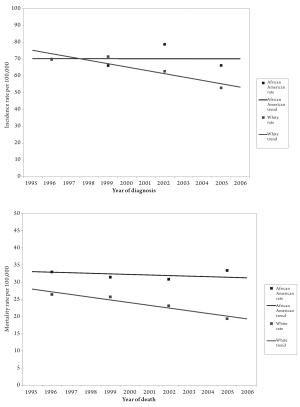

Mortality and incidence, both sexes combined

Incidence: During 1995-2006, CRC was diagnosed in

36,877 Wisconsin residents, including 35,108 whites and

1,192 African Americans. Age-adjusted CRC incidence

decreased 26% from 59 per 100,000 in 1995 to 44 per 100,000 in 2006. Incidence decreased quite dramatically

for whites over the period, but not for African Americans.

Moreover, an absolute disparity in rates persisted, with

African American rates higher than white rates over

virtually the entire period (Figure 3). Relative disparity,

measured using the rat io of the Af r ican Amer ican

incidence rate to the white incidence rate based on the

1995-2006 trend line, grew from 1.0 in 1995 and 1.3 in

2006 (Table 1).

Mortality: From 1995-2006, there were 13,207 deaths

due to CRC among Wisconsin residents, including 12,645

whites and 450 African Americans. Age-adjusted CRC

mortality declined 29% from 22 per 100,000 in 1995 to 16

per 100,000 in 2006. Mortality decreased markedly over the period among whites, but not for African Americans,

and an absolute disparity in rates persisted over the period

(Figure 3). The relative disparity in death rates grew over

the period, with the rate ratio increasing from 1.2 in 1995 to

1.5 in 2006 (Table 1).

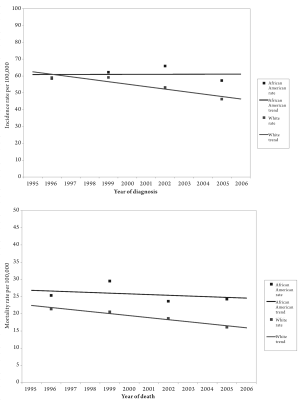

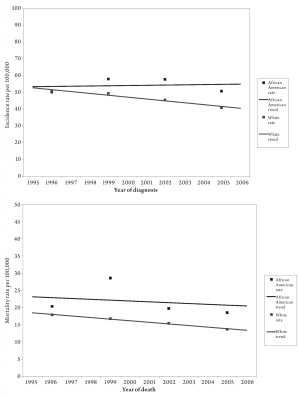

Mortality and incidence, males

Incidence: During 1995-2006, CRC was diagnosed in

18,645 Wisconsin men (including 17,746 whites and 585

African Americans). Over this period, age-adjusted CRC

incidence among men decreased 29% from 70 per 100,000

in 1995 to 50 per 100,000 in 2006. Incidence among

African Americans was higher than that of whites over most

of the period. In addition, while white rates fell, rates for African Americans remained stable (Figure 4). The relative

disparity in male incidence rates grew from a rate ratio of 0.9

in 1995 to 1.3 in 2006 (Table 1).

Mortality: Between 1995 and 2006, there were 6,594

deaths due to CRC among Wisconsin men (including 6,309

whites and 224 African Americans). Over this period, ageadjusted

male CRC mortality decreased 31% from 27.4

per 100,000 in 1995 to 19.0 per 100,000 in 2006. CRC

mortality among African American men was consistently

higher than that among white men. Over the period,

the disparity in CRC mortality rates between African

Americans and white men increased due to the sharper

decline in white rates compared to African American rates

(Figure 4). The ratio between African American and white

CRC mortality rates increased from 1.2 in 1995 to 1.6 in

2006 (Table 1).

Mortality and incidence, females

Incidence: From 1995-2006, CRC was diagnosed in

18,232 Wisconsin women (including 17,362 whites and

607 African Americans). During this period, age-adjusted

CRC incidence among women decreased 24% from 51 per

100,000 in 1995 to 38 per 100,000 in 2006. Over this time

frame, the incidence among African American women was

more than that of white women in nearly every year (Figure

5). The relative disparity in female CRC incidence also

increased as African American rates increased and white

rates decreased. The ratio between African American and

white rates was 1.0 in 1995 and 1.4 in 2006 (Table 1).

Mortality: Between 1995 and 2006, there were 6,613

deaths due to CRC among Wisconsin women (including

6,336 whites and 226 African Americans). During this

period, age-adjusted CRC mortality decreased 28% from 19

per 100,000 in 1995 to 14 per 100,000 in 2006. In this time frame, the disparity in female CRC mortality rates between

African Americans and whites persisted (Figure 5), and the

ratio between African American and white CRC mortality

rates increased from 1.3 in 1995 to 1.5 in 2006 (Table 1).

|

|

Discussion

The results indicate that disparities in CRC incidence

and mortality between African Americans and whites in

Wisconsin are large and have increased over the last decade.

These results are similar in trajectory to those observed at

the national level over the same period, although the scale

of change in Wisconsin was much larger. For the U.S. as

a whole, CRC mortality rates decreased for both whites

and African Americans from 1999 to 2006, but the rate

ratio increased from 1.4 to 1.5. National CRC incidence

rates have also decreased, but the relative disparity has remained stable at 1.2 ( 32). The state-level data are critical

to understanding where Wisconsin is in its effort to

reduce the burden of CRC, and to informing research and

interventions for CRC prevention and control. The reasons for the alarming increase in disparities in

CRC mortality and incidence between African Americans

and whites in Wisconsin are unknown, but may be due to

changes in risk factors in these two populations, such as

obesity. Results from the Wisconsin Behavioral Risk Factor

Survey reveal that between 2000 and 2009, overweight/obesity rates among African Americans increased 26%

(from 64% to 86%). Overweight/obesity rates also

increased among whites, but the increase was much smaller

(11%, from 58% to 65%) ( 33). Low socioeconomic status has been shown to be

associated with an increase in the incidence of and poorer

survival from CRC ( 34, 35). The fact that in Wisconsin,

African Americans are more likely to live in poverty and

less likely to have graduated from high school than whites

( 36) may explain some of the observed CRC disparities.

Cancer disparities have also been explained by differential

access to screening, diagnosis, and treatment ( 2). African

American residents of Wisconsin are twice as likely to be

uninsured as whites ( 36). It is thus possible that African

Americans are less likely to receive appropriate CRC

screening ( 18, 19), appropriate, timely treatment for CRC

( 15, 37-40), or services known to prevent CRC ( 41, 42). The

staging distribution presented here shows that there have

been increasing numbers of limited stage CRC diagnosed

amongst African Americans, suggesting a possible screening

effect. Finally, health care access has also improved for

African Americans. In 1996-2000, the uninsurance rate

among African Americans was 17% ( 47), compared to 13%

in 2001-2005 ( 46). A number of limitations should be considered when

interpreting the results of this study. First, the scope is

limited to differences in CRC incidence and mortality

rates between African American and whites. The decision

to focus on these two groups was determined by the

demographic composition of Wisconsin and the rarity of

cancer events. Wisconsin has relatively small non-white

populations, making the comparisons in the present study

difficult to replicate between other racial or ethnic groups

in the state. Cancer incidence and mortality rates among

many minority populations vary widely from year to year.

However, this variation is likely due to the small size of

the population groups rather than real changes in disease

burden. The African American population in Wisconsin

has been stable in numbers for some time in Wisconsin, and

is concentrated in larger urban areas, chiefly Milwaukee.

This is in contrast to southern United States where African Americans are distributed in rural and urban areas and not

heavily concentrated. Thus, in Wisconsin migration is not

a large issue for the African American population in such a

way to make raise concern about selection bias.

Second, WCRS, as a central state cancer registry

participating in the National Program of Cancer Registries,

maintains a passive system of data collection and therefore,

the various reporting facilities are largely responsible for the

quality and timeliness of the data submissions to WCRS.

Reporting variability may impact the relatively small annual

numbers reported in this analysis. WCRS has made data

collection improvements and suggestions in determining

the race and ethnicity of cancer cases (the numerator for

incidence rates). However, it is likely that an unknown

degree of misclassification or under-reporting of race still

exists. There are no national standards for collecting race

data, and facilities vary in the methods used for collecting

racial and ethnic data. Especially when the number of

cases is relatively small, the quality of data collection and

reporting can greatly impact annual incidence numbers

and rates. Cancer registry stage is also reported in a format

different from the American Joint Commission on Cancer

TNM staging that clinicians use in practice, so one cannot

compare the two directly. The WCRS does not report data

on geographic location, age distribution or socioeconomic

status. Additionally, the treatment data collected in the

WCRS is not reliably validated and so is not reported.

In summary, disparities in CRC incidence and mortality

between African Americans and whites in Wisconsin are

large and have worsened over the period 1995 to 2006.

Statewide action to reduce CRC disparities must start with

this evidence. First, African Americans may fall into a

higher risk group warranting earlier initiation of colorectal

screening than the currently recommended starting age

for all average risk adults. There is also promise in efforts

to reduce exposure to risk factors and improve access

to appropriate screening, treatment, and prevention ( 2)

among all Wisconsin residents, and in particular among

African Americans. Patient navigation is one such tool

( 43-45). Care must be taken that any plan carefully balance

resources and set appropriate priorities to target inequities

in CRC burden.

|

|

Conflict of interest/study support

Guarantor of the article: Noelle LoConte, MD.

Specific author contributions: All authors participated

in the design and analysis of the study and in the writing of

the paper. Nathan Jones and Amy Williamson conducted

the data analyses.

Financial support: This project was supported by grant P30 CA014520 from the National Cancer Institute and

by grant T32HS000083 from the Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality National Research Award (J.W.).

Potential competing interests: None.

|

|

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Mary Foote of the

Wisconsin Cancer Registry for assisting with data access

and interpretation.

|

|

References

- National Cancer Institute [Internet]. Center to Reduce Cancer Health

Disparities. Health disparities defined [updated 2010 Aug 25; cited

2010 Jun 16]. Available from: http://crchd.cancer.gov/disparities/defined.html.[LinkOut]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2010. Atlanta:

American Cancer Society; 2010.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention[Internet]. National

Comprehensive Cancer Control Program.[updated 2011 March 16;

cited 2010 June 7] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/ncccp/.[LinkOut]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer Statistics,

2009. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:225-49.[LinkOut]

- Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA,

Inadomi JM, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines

for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected]. Am J Gastroenterol

2009;104:739-50.[LinkOut]

- Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, Eheman C, Zauber AG, Anderson RN,

et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2006,

featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk

factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer

2010;116:544-73.[LinkOut]

- Polite BN, Dignam JJ, Olopade OI. Colorectal cancer and race:

understanding the differences in outcomes between African Americans

and whites. Med Clin N Am 2005;89:771-93.[LinkOut]

- Polite BN, Dignam JJ, Olopade OI. Colorectal cancer model of

health disparities: understanding mortality differences in minority

populations. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2179-87.[LinkOut]

- Marcella S, Miller JE. Racial differences in colorectal cancer mortality.

The importance of stage and socioeconomic status. J Clin Epidemiol

2001;54:359-66.[LinkOut]

- Mayberry RM, Coates RJ, Hill HA, Click LA, Chen VW, Austin DF, et

al. Determinants of black/white differences in colon cancer survival. J

Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87:1686-93.[LinkOut]

- Jessup JM, McGinnis LS, Steele GD Jr, Menck HR, Winchester DP.

The National Cancer Data Base. Report on colon cancer. Cancer

1996;78:918-26.[LinkOut]

- Alexander D, Jhala N, Chatla C, Steinhauer J, Funkhouser E, Coffey

CS, et al. High-grade tumor differentiation is an indicator of poor

prognosis in African Americans with colonic adenocarcinomas. Cancer 2005;103:2163-70.[LinkOut]

- Alexander D, Chatla C, Funkhouser E, Meleth S, Grizzle WE, Manne

U. Postsurgical disparity in survival between African Americans and

Caucasians with colonic adenocarcinoma. Cancer 2004;101:66-76.[LinkOut]

- Dayal H, Polissar L, Yang CY, Dahlberg S. Race, socioeconomic status,

and other prognostic factors for survival from colo-rectal cancer. J

Chronic Dis 1987;40:857-64.[LinkOut]

- Potosky AL, Harlan LC, Kaplan RS, Johnson KA, Lynch CF. Age,

sex, and racial differences in the use of standard adjuvant therapy for

colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:1192-202.[LinkOut]

- Katkoori VR, Jia X, Shanmugam C, Wan W, Meleth S, Bumpers H, et al.

Prognostic significance of p53 codon 72 polymorphism differs with race

in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:2406-16.[LinkOut]

- Dignam JJ, Polite BN, Yothers G, Raich P, Colangelo L, O’Connell MJ,

et al. Body mass index and outcomes in patients who receive adjuvant

chemotherapy for colon cancer. JNCI 2006;98:1647-54.[LinkOut]

- Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, Rimer BK, Lee NC. Progress in cancer

screening practices in the United States: results from the 2000 National

Health Interview Survey. Cancer 2003;97:1528-40.[LinkOut]

- Laiyemo AO, Doubeni C, Pinsky PF, Doria-Rose VP, Bresalier R,

Lamerato LE, et al. Race and colorectal cancer disparities: healthcare

utilization vs different cancer susceptibilities. J Natl Cancer Inst

2010;102:538-46.[LinkOut]

- Cheng X, Chen VW, Steele B, Ruiz B, Fulton J, Liu L, et al. Subsitespecific

incidence rate and stage of disease in colorectal cancer by

race, gender, and age group in the United States, 1992-1997. Cancer

2001;92:2547-54.[LinkOut]

- Rabeneck L, Davila JA, El-Serag HB. Is there a true “shift” to the

right colon in the incidence of colorectal cancer? Am J Gastroenterol

2003;98:1400-9.[LinkOut]

- Dominitz JA, Samsa GP, Landsman P, Provenzale D. Race, treatment,

and survival among colorectal carcinoma patients in an equal-access

medical system. Cancer 1998;82:2312-20.[LinkOut]

- Dignam JJ, Colangelo L, Tian W, Jones J, Smith R, Wickerham DL, et al.

Outcomes among African-Americans and Caucasians in colon cancer

adjuvant therapy trials: findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant

Breast and Bowel Project. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:1933-40.[LinkOut]

- Nelson RL, Persky V, Turyk M. Determination of factors responsible

for the declining incidence of colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum

1999;42:741-52.[LinkOut]

- American Cancer Society. Wisconsin Cancer Facts & Figures 2007.

Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2007.

- Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services. The Health

of Racial and Ethnic Populations in Wisconsin. In:Minority Health

Program.The Health of Racial and Ethnic Populations in Wisconsin

1996–2000. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Department of Health

and Family Services, Division of Public Health; 2004. 22-6.

- Wisconsin Department of Health Ser vices[Internet]. Wisconsin

Minority Health Program. Updated tables for the Wisconsin Minority

Health Report (January 2007)[updated 2010 July 12;cited 2010 June

30. Available from: http://dhs.wisconsin.gov/wcrs/pubs.htm.[LinkOut]

- Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services. Wisconsin

Cancer Incidence and Mortality. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin

Department of Health and Family Services, Division of Public Health,

Bureau of Health Information and Policy; 2007.

- Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program, National

Cancer Institute[Internet]. Race recode changes[cited 2010 June

30]. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/variables/seer/yr1973_2005/race_ethnicity/.[LinkOut]

- O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Ko CY. Colon cancer survival rates with

the new American Joint Committee on Cancer sixth edition staging. J

Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:1420-5.[LinkOut]

- Carter-Pokras O, Baquet C. What is a “health disparity”? Public Health

Rep 2002;117:426-34.[LinkOut]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health

Statistics[Internet]. Compressed Mortality File 1999-2007[cited 2010

June 25]. Available from: http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd10.html.[LinkOut]

- Office of Health Informatics[Internet]. Wisconsin Interactive Statistics

on Health (WISH) data query system, BRFS Module[updated 2011

March 9;cited 2011 March 8]. Available from: http://dhs.wisconsin.gov/wish/.[LinkOut]

- Siegel RL, Jemal A, Thun MJ, Hao Y, Ward EM. Trends in the incidence

of colorectal cancer in relation to county-level poverty among blacks

and whites. J Natl Med Assoc 2008;100:1441-4.[LinkOut]

- Kinsey T, Jemal A, Liff J, Ward E, Thun M. Secular trends in mortality

from common cancers in the United States by educational attainment,

1993-2001. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:1003-12.[LinkOut]

- Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services. Wisconsin

Minority Health Report, 2001-2005. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin

Department of Health and Family Services, Division of Public Health,

Bureau of Health Information and Policy; 2008.

- Schrag D, Rifas-Shiman S, Saltz L, Bach PB, Begg CB. Adjuvant

chemotherapy use for Medicare beneficiaries with stage II colon cancer.

J Clin Oncol 2002;20:3999- 4005.[LinkOut]

- Demissie K, Oluwole OO, Balasubramanian BA, Osinubi OO, August

D, Rhoads GG. Racial differences in the treatment of colorectal cancer:

a comparison of surgical and radiation therapy between Whites and

Blacks. Ann Epidemiol 2004;14:215-21.[LinkOut]

- Baldwin LM, Dobie SA, Billingsley K, Cai Y, Wright GE, Dominitz JA,

et al. Explaining black-white differences in receipt of recommended

colon cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:1211-20.[LinkOut]

- Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Fuchs CS, Guadagnoli E, Creech CM,

Cress RD, et al. Use of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy

for colorectal cancer in a population-based cohort. J Clin Oncol

2003;21:1293-300.[LinkOut]

- Chlebowski RT, Wactawski-Wende J, Ritenbaugh C, Hubbell FA,

Ascensao J, Rodabough RJ, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and colorectal

cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 2004;350:991-1004.[LinkOut]

- Robertson DJ, Greenberg ER, Beach M, Sandler RS, Ahnen D, Haile

RW, et al. Colorectal cancer in patients under close colonoscopic

surveillance. Gastroenterology 2005;129:34-41.[LinkOut]

- Myers RE, Hyslop T, Sifri R, Bittner-Fagan H, Katurakes NC, Cocroft J, et al. Tailored navigation in colorectal cancer screening. Med Care

2008;46:S123-31.[LinkOut]

- Christie J, Itzkowitz S, Lihau-Nkanza I, Castillo A, Redd W, Jandorf

L. A randomized controlled trial using patient navigation to increase

colonoscopy screening among low-income minorities. J Natl Med Assoc

2008;100:278-84.[LinkOut]

- Chen LA, Santos S, Jandorf L, Christie J, Castillo A, Winkel G, et al. A

program to enhance completion of screening colonoscopy among urban

minorities. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;6:443-50.[LinkOut]

- Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services. The Health of Racial and Ethnic Populations in Wisconsin. In:Minority Health

Program.The Health of Racial and Ethnic Populations in Wisconsin

1996–2000. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Department of Health

and Family Services, Division of Public Health; 2004. 22-6.

- Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services. Wisconsin

Minority Health Report, 2001-2005. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin

Department of Health and Family Services, Division of Public Health,

Bureau of Health Information and Policy; 2008.

Cite this article as:

LoConte N, Williamson A, Gayle A, Weiss J, Leal T, Cetnar J, Mohammed T, Tevaarwerk A, Jones N. Increasing disparity in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality among African Americans and whites: A state’s experience. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;2(2):85-92. DOI:10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2011.014

|