Outcomes of adjuvant radiotherapy and lymph node resection in elderly patients with pancreatic cancer treated with surgery and chemotherapy

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is a common disease in the United States with approximately 43,920 people diagnosed each year, and about 37,390 people will die from their disease (1). The median age at diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is 72, with approximately 43% of all patients being aged ≥75 in the United States (2). Outcomes continue to remain dismal with the only chance of cure being margin negative (R0) resection.

Chemotherapy remains a mainstay of treatment in the adjuvant setting however the addition of post-operative radiation therapy (PORT) continues to be a topic of controversy. Several studies have shown an overall survival (OS) benefit to PORT (3-5) compared to surgery alone while others have demonstrated no benefit and possible detriment (6-8). Some institutions recommend chemotherapy alone and others recommend the addition of PORT.

Age is not a contraindication to surgical resection and has been extensively researched (9-12). Some studies have shown an increased in operative time and post-operative complications in the elderly population however no differences in post-operative mortality thus validating surgical resection in this aging population. Very few studies have looked at PORT and chemotherapy in the elderly population (13,14). The Surveillance Epidemiology End Result (SEER) database is one of the largest repositories of patient outcomes from cancer. Data on age, gender, survival, surgery, radiation, sequence of radiation with surgery, and pathologic variables like grade, lymph node involvement, number of lymph nodes removed, and tumor stage are available. A factor not routinely made available is the use of chemotherapy unless SEER grants special requests to provide data as a yes/no question. We present the first, largest, and most modern analysis of the SEER database on surgically resected pancreatic cancer patients who are age 70 or greater, who all received chemotherapy, to address to role of PORT and lymph node resection (LNR) on survival in this population.

Methods

Patients

After being granted a request to access chemotherapy data from the SEER database, a unique SEER 17-registries 1973–2008 dataset where a chemotherapy variable (yes/no) was now included was queried to identify patients ≥18 years old diagnosed from 2004–2008 with pancreatic adenocarcinoma who underwent curative resection (n=5,373). Included patients were 70 years or older, underwent Whipple, distal pancreatectomy, or total pancreatectomy for AJCC (6th ed) stage I–III cancer, received chemotherapy and either received PORT or no PORT (n=961). Patients were excluded from the analysis if they were 70 years old or younger (n=2,005), no chemotherapy was given (n=1,757), the type of surgery was local excision or unknown (n=129), no or unknown lymph node dissection (n=179), or had less than 3 months survival (n=342). Data not included in SEER include patient co-morbidities, nutritional status, performance status, surgical margin status, radiation dose and field design.

Statistical analysis

Survival was evaluated on the basis of time from date of diagnosis to date of death or censoring. Unadjusted survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method comparing survival curves with the log-rank test. Multivariate analysis (MVA) of prognostic factors related to survival was performed by the Cox Proportional Hazard Regression modeling. Data were analyzed using STATA IC (Stata Statistical Software, Release 10.0; Strata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided and α (type I) error <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

We identified 961 patients who met inclusion criteria (555 PORT, 406 No RT). Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. The only statistically significant difference between the groups was age. Patients receiving PORT had a median age of 75 (range 70–88) vs. 76 (range 70–91) years in patients not treated with PORT (P=0.007). The majority of patients were moderately differentiated, node positive (N1) tumors of the pancreatic head.

Full table

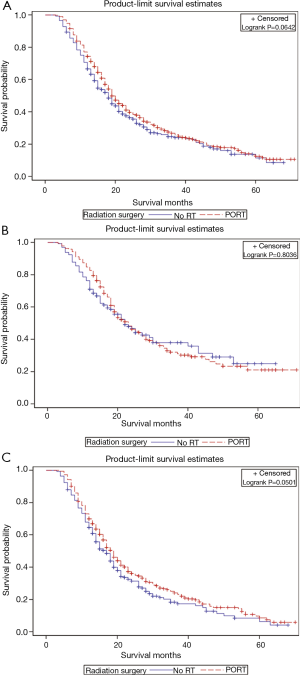

Figure 1 illustrates the OS curves for all patients and according to nodal status stratified by PORT vs. no PORT. Median OS for all patients with PORT was 19 vs. 18 months without PORT (P=0.0642). There was no difference in survival in node negative (N0) patients receiving PORT (P=0.8036), however there was a trend towards improved survival favoring PORT in N1 patients (P=0.0501).

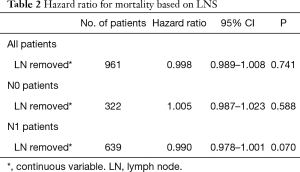

We performed univariate analyses to determine the optimal number of lymph nodes resected both categorically and as a continuous variable (Table 2). In all, N0, and N1 patients there was no associated survival benefit for increasing number of lymph nodes removed.

Full table

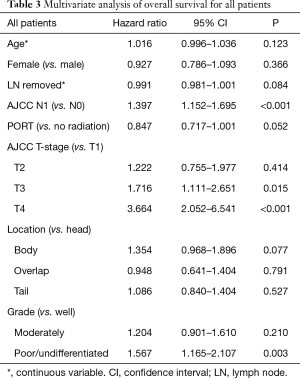

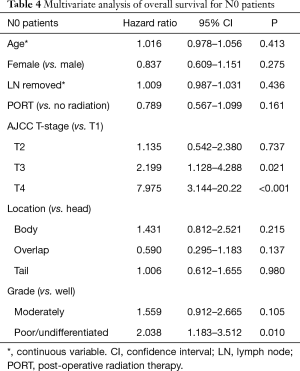

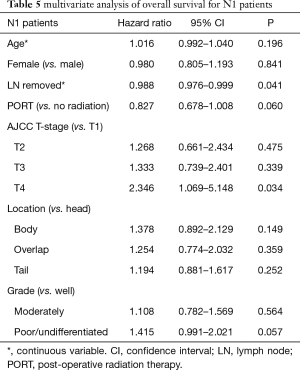

MVA for OS is presented in Tables 3-5. MVA for all patients is presented in Table 3 and revealed that increasing T stage, tumor grade, and N1 status were prognostic for increased mortality, while there was a trend for decreased mortality in the patients receiving PORT (P=0.052). Age, number of lymph nodes removed, tumor location, and gender demonstrated no prognostic significance. MVA for N0 patients showed that increasing T stage and grade were associated with increased mortality (Table 4). Age, gender, tumor location, PORT, and number of lymph nodes removed were not prognostic in N0 patients. MVA for N1 patients indicated that increasing T stage was prognostic for increased mortality and number of lymph nodes removed was prognostic for decreased mortality (Table 5). PORT showed a trend towards decreased mortality (P=0.060) and poorly differentiated tumors showed a trend towards increased mortality (P=0.057). Age, gender, and tumor location, were not prognostic in N1 patients.

Full table

Full table

Full table

Discussion

SEER database analyses are usually criticized for the lack of chemotherapy data. However, we were able to obtain data on chemotherapy from SEER. This is the first, largest, and most modern SEER database analysis on elderly pancreatic cancer patients treated with surgical resection and chemotherapy analyzing the relationship between PORT and LND. We found no statistically significant benefit to the addition of PORT. There was also no difference in OS based on number of lymph nodes removed. MVA for all patients revealed that increasing tumor stage, N1 patients, and higher grade tumors were prognostic for increased mortality. While PORT showed a trend towards decreased mortality, it wasn’t statistically significant. In N0 patients, increasing tumor stage and grade were prognostic for increased mortality, while PORT and number of lymph nodes removed showed no significant prognostic importance. In N1 patients, higher tumor stage and grade were prognostic for worse OS, while increasing number of lymph nodes removed was associated with increased OS. While PORT showed a trend to increased OS in N1 patients, it wasn’t statistically significant.

There continues to be a controversy on the role of PORT in the adjuvant setting in resected pancreatic cancer patients over all ages. There have been several prospective trials which have shown a benefit to the addition of PORT with chemotherapy; which included the elderly patient population. In GITSG 9173 (n=43), patients were randomized to observation or CRT with 40 Gy split-course and concurrent 5-FU after R0 resection (3). Although this study had poor accrual it was closed early when interim analysis showed improvement in median survival in the trimodality group compared to observation (20 vs. 11 months, P=0.035). The EORTC-40891 (n=218) phase III study randomized resected pancreatic cancer or periampullary cancer patients to observation vs. 5-FU based chemoradiotherapy similar to the GITSG trial (15,16). There was no difference in survival in pancreatic cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. The EORTC-40013/FFCD-9203/GERCOR phase II study randomized pancreatic cancer patients after R0 resection to gemcitabine alone vs. gemcitabine followed by CRT (50.4 Gy with weekly gemcitabine) (8). Median OS was 24 months in both groups; however CRT reduced the likelihood of first local recurrence (11% vs. 24%) and was well tolerated. The analysis of the ESPAC-1 trial reported that there was no benefit to adjuvant CRT with possible detriment (7). Despite the criticisms of a complicated trial design and poorer outcomes of chemoradiation patients compared to other trials, adjuvant chemotherapy was adopted as the standard of care in Europe.

Lymphadenectomy in pancreatic cancer is also a controversial topic, however several randomized trials have shown no benefit to extended lymphadenectomy compared to standard lymphadenectomy (17). However, a recent report from RTOG 9704 (18) concluded that removing >12 and >15 lymph nodes was associated with increased survival in node positive patients but not node negative patients on univariate and MVA. In RTOG 9704, all patients were treated with adjuvant chemoradiation therapy. In our analysis, only 58% received adjuvant radiation therapy, however, our findings in regards to lymphadenectomy are similar to RTOG 9704, where we find the benefit of lymphadenectomy is restricted to node positive patients.

Surgery has been shown to be well tolerated in the elderly (9-12). However, there have been few studies addressing the tolerability and outcomes of adjuvant chemoradiation. A study from Harvard analyzed 42 pancreatic cancer patients age 75 years and older treated with chemoradiation therapy either as definitive therapy (n=24) in the locally advanced setting or as adjuvant therapy (n=18) (14). Median OS in the patients that received surgery and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy was 20.6 and 8.6 months in the patients treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy. While outcomes were similar to historical controls, there was substantial treatment-related toxicity necessitating a treatment break and hospitalizations. A study conducted at Johns Hopkins Hospital analyzed the outcomes of patients >75 years with pancreatic cancer who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (13). They identified 166 patients treated between 1993 and 2005 of which 49 (29.5%) received adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. For elderly patients, N1 disease (P=0.008), poorly differentiated tumors (P=0.012), and undergoing a total pancreatectomy (P=0.010) predicted poor survival. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy was associated with a 2-year survival benefit compared with surgery alone (49.0% vs. 31.6%, P=0.013); however, this benefit was lost at 5 years (11.7% vs. 19.8%, respectively, P=0.310). Our analysis of patients age 70 years or older addressing the role of adjuvant radiation in chemotherapy treated patients shows similar results with a median survival of 19 months in radiated patients with no apparent survival benefit on univariate and MVA.

There are several limitations to the use of the SEER retrospective database, most importantly lack of chemotherapy data. Fortunately, chemotherapy data was made available for this analysis after special requests were made. Other information that is missing includes no data on nutritional status and performance status which play an important role in the elderly. However, given that we restricted our analysis to patients who underwent radical resection (Whipple, distal pancreatectomy, and total pancreatectomy), lived at least 3 months, and all were treated with chemotherapy, we feel that this dataset represents a very healthy population that would be able to tolerate surgery and chemotherapy.

Conclusions

This is the first, largest, and most modern analysis of the SEER database which demonstrates in radically resected pancreatic cancer patients, age ≥70 years, who received chemotherapy, that there is marginal survival benefit for the addition of adjuvant radiation therapy or aggressive lymph node dissection. The survival benefit of LNR is limited to node positive patients on MVA, consistent with data from RTOG 9704.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: Presented at American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress in October 2016, Washington DC.

Ethical Statement: The study was IRB approved at Moffitt Cancer Center (NO. #105286Z). The study was IRB approved for waiver of informed consent.

References

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2012;62:10-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2005. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2005/

- Kalser MH, Ellenberg SS. Pancreatic cancer. Adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection. Arch Surg 1985;120:899-903. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herman JM, Swartz MJ, Hsu CC, et al. Analysis of fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: results of a large, prospectively collected database at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3503-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corsini MM, Miller RC, Haddock MG, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy for pancreatic carcinoma: the Mayo Clinic experience (1975-2005). J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3511-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neoptolemos JP, Dunn JA, Stocken DD, et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy in resectable pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2001;358:1576-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, et al. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1200-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Van Laethem JL, Hammel P, Mornex F, et al. Adjuvant gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine-based chemoradiotherapy after curative resection for pancreatic cancer: a randomized EORTC-40013-22012/FFCD-9203/GERCOR phase II study. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4450-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brozzetti S, Mazzoni G, Miccini M, et al. Surgical treatment of pancreatic head carcinoma in elderly patients. Arch Surg 2006;141:137-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Makary MA, Winter JM, Cameron JL, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy in the very elderly. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:347-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brennan MF, Kattan MW, Klimstra D, et al. Prognostic nomogram for patients undergoing resection for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Ann Surg 2004;240:293-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al. Should pancreaticoduodenectomy be performed in octogenarians? J Gastrointest Surg 1998;2:207-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horowitz DP, Hsu CC, Wang J, et al. Adjuvant chemoradiation therapy after pancreaticoduodenectomy in elderly patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011;80:1391-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto DT, Mamon HJ, Ryan DP, et al. Outcomes and tolerability of chemoradiation therapy for pancreatic cancer patients aged 75 years or older. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;77:1171-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J, Sahmoud T, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann Surg 1999;230:776-82; discussion 782-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smeenk HG, van Eijck CH, Hop WC, et al. Long-term survival and metastatic pattern of pancreatic and periampullary cancer after adjuvant chemoradiation or observation: long-term results of EORTC trial 40891. Ann Surg 2007;246:734-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shrikhande SV, Barreto SG. Extended pancreatic resections and lymphadenectomy: An appraisal of the current evidence. World J Gastrointest Surg 2010;2:39-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Showalter TN, Winter KA, Berger AC, et al. The influence of total nodes examined, number of positive nodes, and lymph node ratio on survival after surgical resection and adjuvant chemoradiation for pancreatic cancer: a secondary analysis of RTOG 9704. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011;81:1328-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]