Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are rare neoplasms with wide spectrum of clinical presentations that are

classified according to differentiation, grade, and stage.

Differentiation refers to the degree in which the neoplastic

cells resemble their non-neoplastic equivalent (

1). The

term well-differentiated refers to neoplastic cells that

closely resemble their non-neoplastic counter equivalent

having organoid and nesting appearances; while poorlydifferentiated

is reserved for neoplasms that bear less

resemblance to their cells of origin, and have diffuse

architecture and irregular nuclei (

1). Histologic grade refers

to the aggressiveness of the neoplasm with high-grade

having a more aggressive and less predictive course; poorlydifferentiated

NETs are traditionally considered high grade

(

1). Tumor stage refers to the extend of tumor spread.

Majority of NETs are carcinoid tumors, which are welldifferentiated

and have a better prognosis than the usual

adenocarcinoma. Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma

(LCNEC) is a rare subtype of NETs with an aggressive

nature and a poor prognosis due to its tendency for early

metastasis (

2). While NETs can arise in different organs,

colonic NETs are exceptionally rare (

2,

3). A study by

Bernick et al showed that 0.6% of patients with colorectal

cancer had neuroendocrine carcinoma and only 0.2% of

those were large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas (

4,

5).

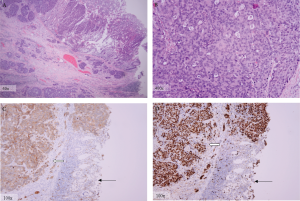

While the colonic LCNET are rare tumors, they share

histological features with the more well described large cell

neuroendocrine carcinomas of the lung. The histological

classification of LCNETs of the lung was initially proposed

by Travis et al (

6) and subsequently adopted by the World

Health Organization. These tumors are characterized by

(i) neuroendocrine appearance under light microscopy

(including an organoid, nesting, trabecular, rosette, and

palisading pattern) (

7), (ii) large cells with a polygonal

shape, ample cytoplasm, coarse chromatin and frequent

nucleoli, (iii) very high mitotic rate (greater than 10/10 highpower

fields) along with frequent necrosis, and evidence

of neuroendocrine features by immunohistochemistry or

electron microscopy (

4,

6).

The tumor in this case met the morphological criteria

proposed by Travis et al (

6), and had neuroendocrine

immunohistochemical features including diffuse

cytoplasmic staining for synaptophysin . Unlike

adenocarcinomas, most poorly differentiated LCNETs, like

the one in this case, are negative for CK-20 (a tumor marker

traditionally confined to the intestinal epithelial, urothelial,

and Merkel cells) (

8). Nonetheless, several case reports of

CK-20 positive LCNEC have been reported in the literature,

suggesting a potentially common precursor for these tumors

and the conventional colonic adenocarcinomas (

2,

3,

9).

Ki-67 antige is a surrogate marker for cell proliferation

and is detected in the nucleus of actively cycling cells. Since Ki-67 is strictly related to cell replication and not to

DNA repair, it can serve as an excellent marker for tumor

growth (

10). In the case presented, 90% of the tumor cell

nuclei stained positive for Ki-67, demonstrating its highly

aggressive nature with rapid metastases to the liver. While

tumor aggressiveness of the tumor has been associated

to the extent of Ki-67 expression in some studies (

11,

12),

others have argued that the prognostic value of Ki-67

is dependent on the tissue type and that it may not be

generalized to all tumors (

13). Similarly, prognostic value

of Ki-67 in LCNECs is unclear at this time.

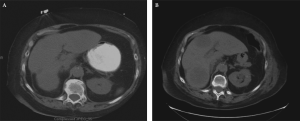

Similar to the adenocarcinomas of the colon, liver is the

most common site of metastasis for the NETs of the colon

(

14). Given the aggressive nature of colonic NET, patients

most often present with metastatic disease at time of initial

diagnosis (

4). The aggressive nature of colonic large cell

neuroendocrine tumors is evident in this case by the rapid

progression of the tumor and near replacement of the liver

by tumor in a period spanning approximately 10 days

from the time of initial presentation to the time of second

operative exploration.

In conclusion, colonic large-cell neuroendocrine

carcinomas are rare and aggressive tumors. Most are located

in the cecum or the rectum, are metastatic at presentation,

and have a poor prognosis with median overall survival

reported to be 10.4 months (range of 0 to 263.7 months)

(

4). While surgical resection is the primary treatment

modality, the benefit of chemo- or radiation therapy, as used

for conventional colorectal adenocarcinomas, has not been

established for colonic LCNET (

3,

4,

15,

16). Interestingly a

recent case report indicated clinical benefit to post-operative

chemoradiation in a patient with LCNET (17). Thus further

studies are needed to determine the molecular genetics of

these rare tumors and define the optimal systemic and local

therapies.