Can pancreaticoduodenectomy performed at a comprehensive

community cancer center have comparable results as major

tertiary center?

Appleton Medical Center, Fox Valley Surgical Associates, Appleton, Wisconsin, USA

|

Original Article

Can pancreaticoduodenectomy performed at a comprehensive

community cancer center have comparable results as major

tertiary center?

Appleton Medical Center, Fox Valley Surgical Associates, Appleton, Wisconsin, USA

|

|

Abstract

Background: Pancreatic resection is a definitive treatment modality for pancreatic neoplasm. Pancreaticoduodenectomy

(PD) is the primary procedure for tumor arising from head of pancreas. Prognosis is overwhelmingly poor despite

adequate resection. We maintained a prospective database covering years 2001 to 2010. Outcome data is analyzed and

compared with those from tertiary centers.

Methods: Sixty-two patients with various histology were included. Pylorus preserving pancreatico-duodenectomy

(PPPD), classic pancreaticoduodenectomy, and subtotal pancreatectomy were procedures performed. Three patients had

portal venorrhaphy performed to obtain clinically negative margin. Forty six patients had malignancy on final pathologic

analysis.

Results: The average age of patients was 63. Mean preoperative CA19-9 for exocrine pancreatic malignancies was

higher than for more benign lesions. There was a decrease in operative time during this period. Blood transfusion was

uncommon. There was very few pancreatic leak among the patients. Two bile leaks were identified, one controlled with

the drainage tube and the other one required repeat surgery. The primary reason for the prolonged hospitalization was

gastric ileus. For patients without a gastrostomy tube, nasogastric tube was kept in until gastric ileus resolved. 30 days

mortality rate was calculated at 4.8. Mean survival time during our follow up was 30.6 months. Comparing to published

literature, present series’ mortality, morbidity, and survival are similar. Five year survival was 39%.

Conclusion: Despite overall poor outcome for patients with pancreatic and biliary malignancies, we conclude that

surgery can be performed in community hospitals with special interest in treating pancreatic disorder, offering patients

equivalent survival and quality of life as those operated in tertiary centers.

Key words

Pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer; surgical outcome; community hospital

J Gastrointest Oncol 2011; 2: 143-150. DOI: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2011.035

|

|

Introduction

With about 44000 new cases and about 37600 cancer deaths

in 2011, pancreatic cancer ranks fourth among cancerrelated

deaths in the United States. It is the second leading cause of death due to gastrointestinal tract neoplasm. It is

one of the few cancers whose survival has not improved over

the past 40 years (1).

Pancreatic cancer affects more commonly elderly, and

less than 20% of patients present with localized, potentially

curable tumors (2). The average life expectancy after

diagnosis with metastatic disease is three to six months.

Average five year survival is 6%. Seventy-five percent of

patients die within first year of diagnosis. Pancreatic cancer

has the highest death rate of all major cancers (3).

Symptoms of pancreatic cancer depend on the location,

as well as on the stage of the disease. Significant number

of tumors develops in the head of the pancreas and

usually led to cholestasis, abdominal discomfort and

nausea. Obstruction of the pancreatic duct may lead to pancreatitis. Most patients have systemic manifestations of

the disease such as asthenia, anorexia, and weight loss. Less

common manifestations include venous thrombosis, liverdysfunction,

gastric obstruction, and depression (4-6).

Pancreaticoduodectomy (PD) is the most commonly

performed surgery in patients with pancreatic cancer as 75%

of tumors are located at head of pancreas. First successful

pancreatic head resection was described by Walter Kausch

in 1912, and later modified by Allen O Whipple in 1935 as

two stage procedure whereby diversion was followed by

definitive resection (7,8).

|

|

Method

In Appleton, Wisconsin, a community hospital cancer

center was established in 2001. Patients underwent PD

were followed from 2001 to 2010, 62 PD’s were performed

during this time interval by a surgical team with interest in

gastrointestinal oncology. The results were compared with

a large series of similar surgery performed elsewhere in the

United States (9). The retrospective analysis of the database

was approved by the local Institutional Review Board of

ThedaCare Hospitals.

SAS 9.2 statistical sof tware was used to perform

statistical analysis. Student t-test was used to test the mean

difference between two groups of patients. Fisher’s exact

test was used to examine the association between two

factors in a table. Kaplan Meier survival curves were used to

estimate survival.

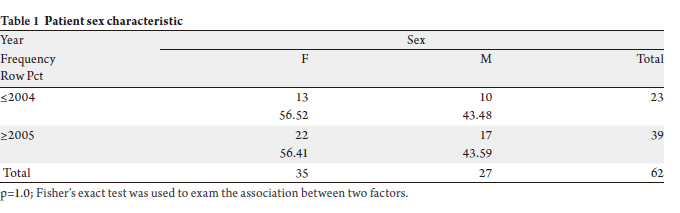

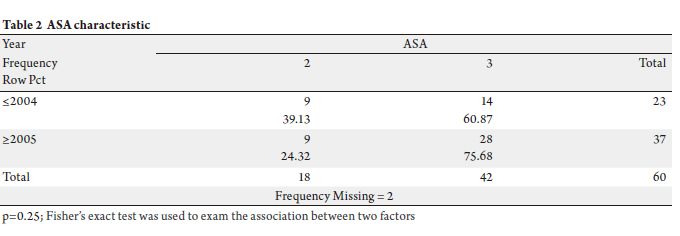

A total of 62 patients (female 35, male 27) with histologyproven

pancreatic cancer, ampullary carcinoma and other

histological types, including benign histological entities,

were included in the study (Tables 1 & 2). To query on the

difference in outcome between the early and later time

interval, we arbitrarily analyzed patients operated before

and after year 2005.

Pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy

(PPPD) was performed in forty one patients; twenty

patients had traditional PD and one patient with subtotal

pancreatectomy. Clinical pathway was adapted and utilized

uniformly in the later period. Three patients had portal

venorrhaphy due to tumor adherence to the portal vein.

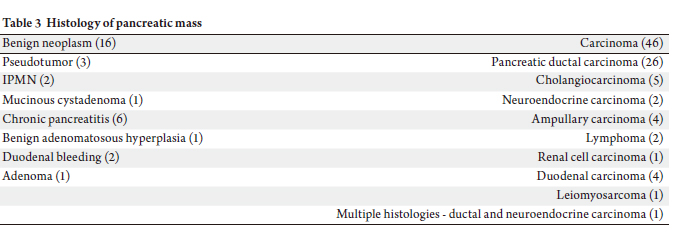

Forty six patients had malignant diagnoses, whereas sixteen

patients had benign histology. One case had dual histology

(ductal carcinoma and neuroendocrine tumor).

Final pathology showed pancreatic adenocarcinoma,

cholangiocarcinoma, adenoma, lymphoma, ampullary

carcinoma, duodenum carcinoma, leiomyosarcom, isolated

metastatic carcinoma to pancreas, and neuroendocrine

tumor. Benign histological diagnoses included,

pancreatitis, IPMN, pseudotumor, and adenomatous hyperplasia (Table 3).

Majority of patients presented with jaundice, weight

loss and abdominal pain. All of the patients had computed

tomography scan done as part of their evaluation.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

was performed for patients with symptoms related to bile

duct obstruction. Preoperative biliary stents were placed

at the discretion of the endoscopist, with relief of jaundice

being the primary intent.

Mean age of patients was 63 years, with ages ranging

from 39 to 78 years. Ethnicity among the patients included

34 Caucasians, 3 Asians, 5 Hispanics, and 13 patients of

unknown origin.

|

|

Clinical data

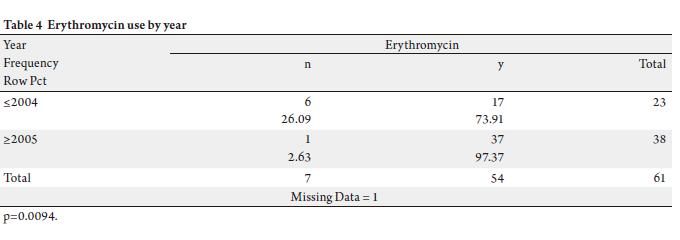

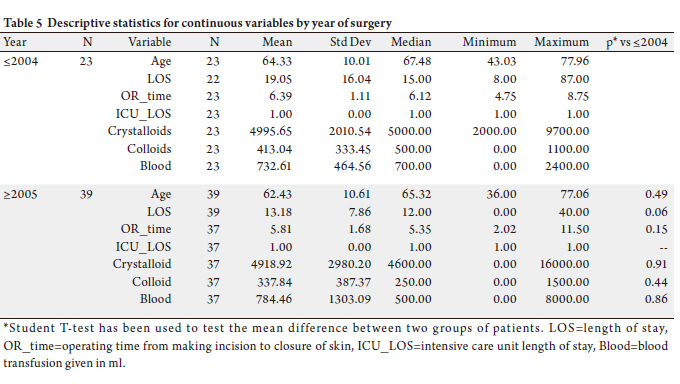

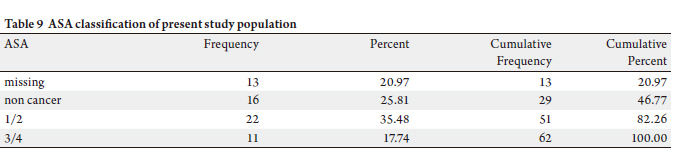

Average operative time was 385 minutes for surgeries

performed before 2005 and 348 minutes for surgeries

performed after 2005. Comparing procedures performed

pre-and post-2005, length of hospital stay was shorter

(nearly reaching statistical significance) adjusted for

gender, age, and ASA (p=0.06). Average length of stay for

all patients was 16.1 days (range 0-87 days), mean ICU

stay was 3 days (range 1-63 days). Among the covariates

examined, only erythromycin use (as motility agent)

changed significantly: there was a substantial increase

in its usage (p=0.009). Erythromycin was ordered for 17

(73.91%) patients out of 23 surgeries performed before

2005 and 97.4% of patients received Erythromycin after the

surgery (Table 4).

Blood transfusion was given to 15 patients requiring

blood product. Mean preoperative CA19-9 for exocrine

pancreatic malignancies was 638, whereas for benign lesions

and endocrine tumors it was 122 (Table 5).

There were three perioperative deaths due to ischemic

bowel and severe acidosis, equivalent to thirty day mortality

rate of 4.8%. Major causes of 30 day postoperative death in

our study were small bowel necrosis (ii) and disseminated

intravascular coagulopathy (i). There was one pancreatic

leak in our patient population. Two bile leaks were

identified, one controlled with the drainage tube and one

required laparotomy to repair the leak. Average length

of stay was 15 days. The primary reason for prolonged

hospitalization was gastric ileus. For patients without a

gastrostomy tube, nasogastric tube was kept in until gastric

ileus resolved.

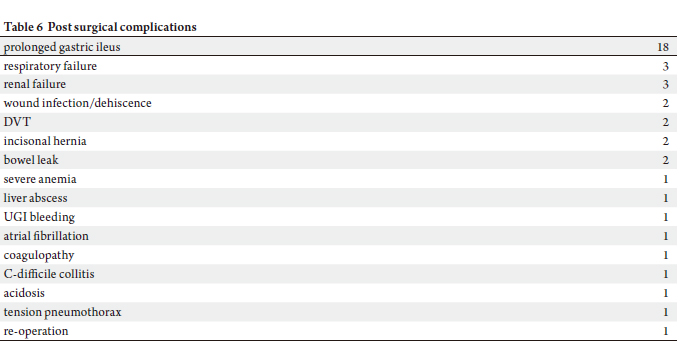

Respiratory failure and renal failure occurred in 4.8% of

patients. Wound infection, DVT, and incisional hernia each

comprises 3.2% of our patient population (Table 6).

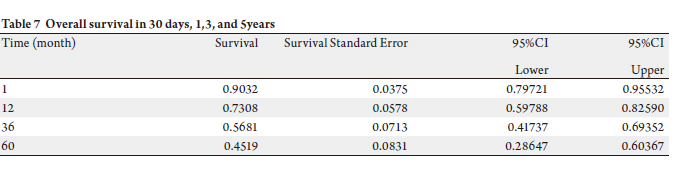

To date, 45% of our patients (N=28) have died, with

two patients from causes unrelated to carcinoma. Mean survival during our study period was 30.6 months for all 62

individuals (Tables 7 & 8). Three year survival for patients

with pancreatic cancer and carcinoma of non pancreas

origin were 39% and 66%, respectively.

In our series of patients, 47.9% had metastatic disease

in regional lymph nodes. 14.2% had positive margins.

For patients without lymph node metastasis and negative

margin, survival was 75%, 47%, and 47% at 12, 36 and

60 months post surger y, respectively. Patients with lymph node metastasis had 5 years survival rate of 39%

whereas those without lymph node involvement had

5 year survival of 48%. Majority of the patients were

of fered adjuvant chemoradiation therapy based on

tumor size greater than 2 cm or if lymph node metastasis

was present. Overall five year survival in this patient

population was 39% (Fig 1). Stage of cancer does not

appear to have an impact on survival. Stages I/II had

5 year survival of 36%, and stages III/IV patients had survival of 34% (Fig 2).

|

|

Discussion

Our results were produced in a comprehensive community

cancer center accredited by the American College of

Surgeons Commission on Cancer. Multidisciplinary

discussions were held during regularly scheduled tumor

conferences. Many of the services providing diagnostic and

therapeutic work up are readily available within the medical

complex. Specialists with interest in gastrointestinal

oncology participate in discussion forums to formulate

treatment plans for each patient. Treatment progress notes

are made available shortly after each encounter with the

patient with an electronic medical record system.

There are numerous publications demonstrating an

improvement of outcome after PD in high volume medical

centers (10-13). Surgeon volume alone also significantly

decreases mortality for complex procedures (14). An

analysis of high volume centers has shown that there is

a significant variability in mortality (0.7% to 7.7%) and,

with other variables analyzed, demonstrates that the variability cannot be explained by hospital volume alone

(15). Surgeon experience is an important determinant of

overall morbidity. In the same study, it was concluded that

experienced surgeons (those who have performed more

than fifty PD) have equivalent results whether they are high

volume surgeons (some performing more than 20 PD per

year) or low volume surgeons (16).

In the literature, five year survival for pancreatic cancer

patients treated with PD ranged from 3% in the early series

to 20% in more recent publications (16-18). In our series,

five year overall survival for patients treated for carcinoma

was 39% .

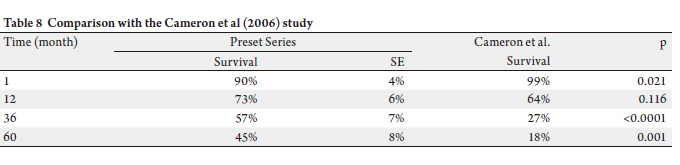

We have chosen a single institution series from Johns

Hopkins with one thousand consecutive PD to compare the

results between the two institutions. Mortality, morbidity,

and survivals are similar (19,20).

The learning curve in pancreatic surgery suggested that

after 60 PD’s, there are improved outcomes of estimated

blood loss, operative time, length of stay, and margin status

— factors which have been associated with overall outcome

(21). The results presented in this study are consistent with

the conclusions presented by published literature.

The benefits of regionalization of complex surgery were

demonstrated in a number of studies. Benefits of a high

volume center include a decrease in mortality and cost and

the ability to perform prospective randomized trials and to

provide surgical training (22,23).

One of the goals of this study is to determine if we

can provide excellent care to patients diagnosed with

periampullary tumors. The closest medical center with

pancreaticobiliary service to our center is approximately

90 miles. Given the choice for location of service, an

overwhelming majority of patients preferred not to travel

long distances. Having a pancreaticobiliary service in our

encatchment area serves to facilitate treatment as well as to

allow patient’s family members easier access to the treating

medical center.

There has been a dramatic improvement of surgical care

in treating periampullary tumors over the last two decades.

Anesthetic and perioperative care during the duration of

our study have made the greatest contribution to decreasing

perioperative mortality. The development of clinical

pathways also has contributed to optimizing the outcome

(24).

There are limitations to a single institutional series such

as ours. Patient population is not large. Because of the

small number of patients, meaningful statistical analysis

is difficult to derive. Morbidity, mortality, and long term

outcomes (cancer specific survival, overall survival)

nevertheless have utility in assessing a cancer program.

The data presented here gives support to continuing the

pancreaticobiliary program at our institution.

Our results ref lect the dedication of specialists with

interest in treating pancreaticobiliary disorders. We assert

that hospital volume alone cannot be the sole determinant

of outcome. It is our belief that surgeon volume combined

with a multidisciplinary approach and excellent ancillary

support provide an excellent prediction of survival as

demonstrated in this study of patients with pancreatic and

biliary malignancies.

The factors contributing to improved survival for patients

diagnosed with periampullary tumors are numerous.

Improved perioperative critical care and improved surgical

care decrease operating time. Advances in adjunctive

therapies contribute to improved survival. It is through

these novel therapies that we will see further improvement

in survival rates (25).

|

|

References

Cite this article as:

Cheng C, Duppler D, Jaremko B. Can pancreaticoduodenectomy performed at a comprehensive

community cancer center have comparable results as major

tertiary center? J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;2(3):143-150. DOI:10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2011.035

|