With the rising identification of incidental pancreatic

cystic lesions, clinicians must be aware of the complexity

in their management. First, one must differentiate between

neoplastic mucinous and nonmucinous cysts which are

managed quite differently. Nonmucinous lesions may be

inf lammatory pseudocysts or neoplastic such as serous

cystadenomas, but if accurately characterized, most do not

require resection or long term follow-up. On the contrary,

mucinous neoplasms (comprised of mucinous cystic

neoplasms (MCN) and intraductal papillary mucinous

neoplasms (IPMN)) have a known premalignant potential,

and therefore are either resected or monitored in a

surveillance program.

The critical issue being faced in routine clinical practice

is accurate preoperative characterization of cystic lesions.

Histology remains the gold standard, but requires resection.

Since that is impractical for most low risk lesions, imaging

provides indirect evidence of morphology. Characterization

of cyst fluid has been touted as a more accurate means define

the nature of pancreatic cysts. Cyst fluid CEA obtained

at time of endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration

(EUS/FNA) remains the most accurate test to distinguish

mucinous from non-mucinous cysts, though its diagnostic

accuracy remains roughly 80% (

1). Unfortunately, the

performance of cytology is poor as well, due in part to

the lack of cellularity in aspirates (

2). The fact that 1 in 5

patients may be incorrectly characterized by state of the art evaluation remains an enormous challenge in daily patient

management leading experts to question the value of the

test for routine cyst characterization.

In 2006, International Consensus Guidelines were

developed by a team of experts to define management of

cystic mucinous neoplasms (

3). They emphasize that the

decision to undergo surgical resection versus surveillance

of a presumed neoplastic cyst should be tempered by the

patient’s wishes, comorbidities, life expectancy and the risk

of malignancy versus the risk of surgery. If the patient is an

appropriate surgical candidate, the guidelines recommend

resection of all MCNs, any IPMN which involve the

main duct or side-branch IPMN (SB-IPMN) which are

symptomatic, have a solid component, or are greater than

3cm in size (

3). Cysts without these worrisome features

should be monitored by imaging at 6-12 month intervals.

While these recommendations appear straightforward,

there remain unresolved challenges in their application

to patient management. According to the guidelines,

one should distinguish between MCN and IPMN, and

in particular focal SB-IPMN, since the former should be

resected whereas the latter can be monitored.

To date, imaging alone or combined with a battery of

tests (fluid analysis, serum markers) fail to adequately

addresses these challenges. Thus guidelines must rely on

a presumptive diagnosis based on imperfect tools, which

as expected, lead to imperfect selection of patients for

surgical intervention. Given the morbidity and mortality of

pancreatic surgery, it is not surprising efforts to better select

patients for resection are a source of active investigation.

Al-Rashdan et al. attempt to critically evaluate this

confusing maze of data and ask whether cyst fluid analysis

really addresses this unmet clinical quandary of how to

appropriately select patients with pancreatic cysts for

surgery (

4). They focus on the challenge to distinguish

between mucinous subtypes by evaluating cyst fluid CEA

and amylase. In the 10 year study period, they identified 134 patients with pancreatic cysts who underwent surgical

resection. Of these patients, 82 underwent a preoperative

EUS. Sixty-six of the 82 were mucinous cysts (14 MCN, 52

IPMN). Of these 66, 25 had preceding FNA and cyst fluid

analysis performed (9 MCN, 11 SB-IPMN and 5 main duct

IPMN). The median and mean CEA were not statistically

different between the 9 MCN and all 16 IPMN (p=0.19),

as well as, MCN and SB-IPMN (p=0.34). The median and

mean amylase were not statistically different between the

MCN and all IPMN (p=0.64) and MCN and SB-IPMN

(p=0.92). Of note, no data was provided regarding crosssectional

imaging or EUS findings.

Their data is similar to other studies that have found

limitations in the accuracy of cyst fluid CEA and amylase--

as well as its selective utilization in practice. In a cohort of

33 mucinous cystadenomas and 235 IPMN patients (

5),

Slozek et al. showed that neither CEA nor amylase was

unable to distinguish between mucinous cystadenomas

and IPMN (p=0.26 and 0.23 respectively). However, for

this study, how many of the pathologic diagnoses were

confirmed by surgical pathology or how the definition

of mucinous cystadenoma was made was not provided.

Curiously, cyst fluid CA19-9 was noted to distinguish

mucinous cystadenomas and IPMN (p=0.003) (

5).

The elevated CA19-9 raises the possibility of a different

biomarker to distinguish between types of mucinous cysts.

Another study of 14 MCN and 52 IPMN cases confirmed

by surgical pathology reported median CEA of 2844 ng/ml

(range 1-14,500) in MCN and 574 ng/ml (0-38,500) in

IPMN (

5). While statistical analysis of this difference was

not reported, the overlap between CEA concentrations is

readily apparent. Most recently, in a study of 126 patients,

Park et al. reported overlapping median values cyst f luid

CEA between MCN and IPMN (428ng/ml [interquartile

range IQR: 44-7870] and 414ng/ml [IQR 102-1223]), again

without statistical analysis (

7). Median values (and IQR)

for cyst f luid amylase overlapped as well for MCN and

IPMN (6800 IU/L [IQR 70-25,295] and 5090 IU/L [IQR

1119-38,290], respectively) (

7).

The data from Al-Rashdan et al. adds to the growing

body of evidence that cyst fluid analysis (CEA and amylase)

alone is disappointing in its ability to distinguish between

the mucinous lesions, MCN and IPMN. However, the

question is we would ever look at cyst fluid analysis alone to

make our clinical decisions? The answer is probably not.

The ability to distinguish clinically between the two

mucinous types requires a broader perspective whereby

imaging and patient factors play a well-documented

role. Crippa et al. highlight the clinical and demographic

differences between 168 patients with MCN and 159

with branch-duct IPMN (

8). Patients with MCN were significantly younger (median 44.5 v. 66 yo, p=0.001) and

almost exclusively women (95% v 57%, p=0.01) (

8). MCN

were most likely to be distal (97% v 25%, p =0.001) and

were more likely to present with abdominal pain (62% v

45%, p=0.004) (

8). IPMNs were also more likely to have a

family history of pancreatic cancer (11% v 3.5%, p=0.01)

and a history of other neoplasms (20 v 9%, p=0.006) (

8).

Moreover, MCN are thought to be separate from the main

pancreatic duct whereas side-branch IPMNs are connected

to the main duct. Of course, distinguishing MCN from

SB-IPMN is not always so straightforward as MCN are

reported to be connected to the main duct in up to 20% of

cases (

9).

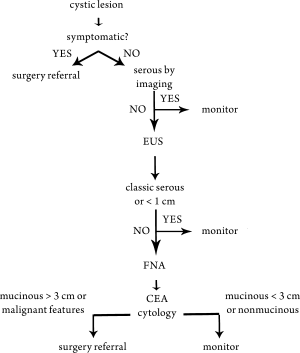

At the University of Michigan, as well as other expert

centers, multidisciplinary care involving gastroenterologists,

radiologists, and surgeons and oncologists have become

a valuable addition to the care of patients with pancreatic

cysts. Careful review of the patient’s history in the context

of cross-sectional imaging, surgical risks, and an estimate

of malignancy risk are taken into account with regard to

clinical decisions. EUS and FNA also play an important

role but are used selectively—it may serve as a confirmatory

role (fluid analysis supporting mucinous etiology or benign

nonmucinous etiology) and for high resolution imaging to

rule out any solid component (See

Fig 1).

What the Al-Rashdan study fails to explore is the clinical

context in which the cyst fluid analysis was drawn. We do

not know demographic information, imaging findings, or

symptoms of the patient. This kind of information is likely

to have played a stronger role than cyst fluid analysis in

distinguishing the two etiologies and in driving the decision

for resection. For example, multifocal cystic disease or an

isolated lesion in the tail in a male is almost certainly IPMN

and may not need resection. The critical question is whether

any type cyst fluid analysis can add incremental value for

such patients—such as prediction of malignancy risk. This

is particularly important in clinically equivocal cases, such

as a woman with a solitary lesion in the body or tail whose

lesion is not clearly distinct from the main duct. In its

current state, CEA and amylase are clearly inadequate and

better biomarkers clearly needed.

There are a number of recent investigations to

evaluate other cyst fluid biomarkers that may aid in the

differentiation of mucinous cyst types. Prostaglandin (

2)

has been shown to have increased expression in pancreatic

cancer tissue over normal pancreatic tissue (

10) and may

also distinguish between types of mucinous cysts. One

study demonstrated that cyst fluid PGE (

2) concentrations

were greater in IPMNs versus MCNs (2.2 ± 0.6 v. 0.2 ±

0.1 pg/mol, p<0.05) (

11). However, there was noted to be an

overlap in PGE (

2) concentrations in benign MCNs and SCAs, thus limiting the utility of this biomarker in the clinical

setting. These findings have not been validated in a larger

study and will require further investigation before it is ready

for clinical application.

Proteomic analysis of cyst fluid in a study of 8 patients

who underwent surgical resection for symptomatic

pancreatic neoplasms identified 92 proteins unique to

MCNs and 29 unique to IPMNs (

12). Analysis identified

several proteins identified in the mucinous lesions (MCN

and IPMN) that were previously reported to be upregulated

pancreatic cancer-associated proteins. The

findings were confirmed by immunohistochemistry for two

of the identified proteins, olfactomedin-4 (OLFM4) and

the cell surface glycoprotein MUC18 (

12). These are very

promising preliminary data which will need to be validated

in future studies.

Using a novel antibody-lectin sandwich array that targets

glycan moieties on proteins (

13), Haab et al. measured

protein expression and glycosylation of MUC1, MUC5AC,

MUC16, CEA, and other proteins associated with

pancreatic cancer in 53 cyst fluid samples (

14). Wheat germ

agglutination of MUC5AC was markedly elevated in MCN

and IPMN but not serous cystadenomas or pseudocysts.

CA19-9 could distinguish between MCN and IPMN with

a sensitivity and specificity of 82% and 93%, respectively.

While these three aforementioned studies of biomarkers are not yet ready for “prime time”, they show potential of

molecular techniques to identify biomarkers that may prove

more useful than CEA or amylase. Much larger sample sizes

will be needed in future validation studies.

This JGO paper reemphasizes that the decision to send

a patient with a pancreatic cyst for resection is complex,

and requires a lot more than just EUS/ FNA with cyst

fluid characterization. Their series confirms the results of

others that amylase levels are of such limited value they

likely should be abandoned. EUS/FNA does have small but

measureable risks of bleeding, infection and pancreatitis;

therefore, we agree with our Indiana University colleagues

and suggest EUS-FNA with CEA levels should be used only

when the results change management. We eagerly await the

identification and development of future biomarkers which

will make “the juice really worth the squeeze.”