Survey results of US radiation oncology providers’ contextual engagement of watch-and-wait beliefs after a complete clinical response to chemoradiation in patients with local rectal cancer

Introduction

The standard treatment for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) is fluoropyrimidine-based neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy (CRT) followed by total mesorectal excision (TME) and post-operative chemotherapy (CT) (1). Over the past decade a novel approach of omitting TME in patients who achieve a complete response to neoadjuvant CRT has been tested in the institution of University of São Paulo Medical School (2). This approach—termed watchful waiting—assumes meticulous following of patients who achieved complete response with immediate salvage surgery in the 20–30% who develop a local recurrence (3). This approach was replicated in other institutions (4) and was further supported by the OnCoRe Project, a large prospective multi-institutional propensity-score matched cohort analysis study (5).

Given the relative novelty of this approach, the lack of evidence from randomized clinical trials, and the need for multi-disciplinary expertise and commitment to this program, many physicians may not feel comfortable with recommending watchful waiting to their patients. Physicians’ attitudes are likely to influence the adoption of this strategy in routine clinical practice. Current attitudes toward watchful waiting among US radiation oncologists (ROs) is unknown.

Methods

Survey instrument development and data collection

This study was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board. We designed an online survey using REDCap software licensed by the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (OCTRI). The survey consisted of 14 questions pertaining to respondents’ characteristics, non-surgical management of patients who achieved a complete clinical response (cCR) to neoadjuvant CRT and self-rated knowledge of the published OnCoRe Project. The online survey was sent anonymously by the REDCap data collecting software to 6,949 potential participants. Email invitations were sent in batches on November 16th and 17th of 2016 and a single reminder email was sent on November 30th, 2016.

Statistical analysis

Respondent characteristics (years in practice, practice setting, region of practice, number of rectal patients treated per year) were tested for associations with respondents’ self-assessed approach to watch-and-wait in patients with rectal cancer using Chi-squared or Fisher’s Exact test, as indicated. Respondents were classified as supporters of watch-and-wait approach if they marked any of the following 6 options: “Data support observation after clinical response to chemoRT, but it is not appropriate for me to start the discussion with the patient, as it should be done by a rectal surgeon”, “Data support observation after clinical response to chemoRT, but I still feel uncomfortable starting this discussion myself”, “Data support observation after clinical response to chemoRT, and I feel comfortable discussing this option with the patient”, “If the patient asks about not doing surgery, data support observation, but I will defer the discussion to a rectal surgeon”, “If the patient asks about not doing surgery, data support observation, but I feel uncomfortable having this discussion with the patient”, or “If the patient asks about not doing surgery, data support observation and I feel comfortable discussing this option with the patient”. Those classified as supporters of observation were further subclassified by their comfort level in leading the discussion of watch-and-wait. Respondents were identified as comfortable if they marked either of the following: “Data support observation after clinical response to chemoRT, and I feel comfortable discussing this option with the patient” or “If the patient asks about not doing surgery, data support observation and I feel comfortable discussing this option with the patient.” A P value of less than 0.05 was defined as statistically significant. R [version 3.3.3 (2017-03-06)] was used for all data analysis.

Results

Respondent characteristics

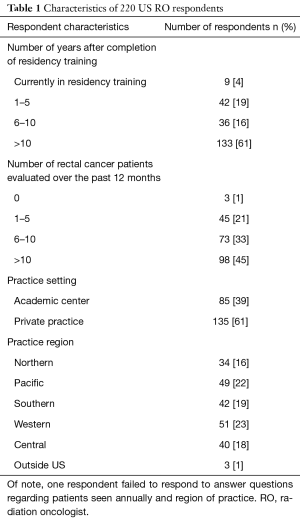

Many of the 6,949 email addresses in our database of potential participants were duplicates or belonged to the same physicians as these physicians are registered with both personal and institutional email accounts, making the determination of the response rate highly inaccurate. We received 337 failed/undelivered automatic responses, 7 non-applicable/ineligible responses and 220 completed responses. The characteristics of these 220 ROs are summarized in Table 1. Of the respondents, 61% practiced over 10 years since completion of residency training, 61% work in private practice, and 55% treat 10 or fewer patients with rectal cancer per year.

Full table

Attitudes toward watch-and-wait approach

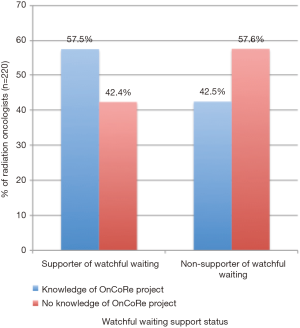

Of the 220 responses, 48% of respondents (n=106) support the watch-and-wait approach. Forty percent claimed familiarity with the OnCoRe Project publication. Respondents supporting observation were more likely to be familiar with the OnCoRe Project (Figure 1, P=0.029).

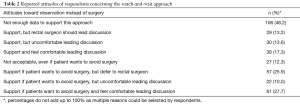

Respondents were able to select multiple responses in the survey. As such, percentages do not add up to 100%. In total 48.2% of the respondents believe there is not enough data to support observation of patients who achieved a cCR in response to CRT and 12.3% are not willing to accept this approach even per patient’s request (Table 2).

Full table

Comfort level in leading discussion

Percentages do not add up to 100% as multiple reasons could be selected by respondents as listed in the previous section. Among supporters of observation, 59% (n=62) felt comfortable discussing the watch-and-wait approach and 41% preferred the conversation be initiated by other specialists. If patients are requesting to avoid surgery, 25.9% of respondents would support them, but would defer to a rectal surgeon, and 17.3% of respondents would feel comfortable leading the discussion themselves (Table 2).

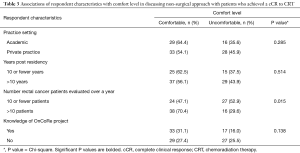

A third of respondents who are familiar with OnCoRe Project report feeling comfortable discussing watch-and-wait with patients. However, there is no association between knowledge of the trial and level of comfort (Table 3).

Full table

ROs treating more than 10 LARC patients annually felt more comfortable leading this discussion (Table 3, P=0.015) compared to ROs seeing fewer patients.

Discussion

In 2006, Habr-Gama and colleagues, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, engineered the watch-and-wait policy after noting 26% to 38% of patients from several institutional-level series achieved a cCR after CRT (2,6). In the largest series (7), 99 out of 122 patients managed under watchful waiting sustained a cCR for at least 1 year. Of the 99 patients, 13.1% had recurrences, with 5% classified as endorectal; all endorectal recurrences were salvaged. The mean recurrence interval was 52 months for local failure. Overall and disease-free 5-year survivals were 93% and 85% (7).

Additional investigators studied watch-and-wait approach. Sanghera et al. from Birmingham, UK, found neoadjuvant CRT can lead to a cCR in up to 42% of patients in 2008 (8). In 2015, Appelt and colleagues studied watchful waiting in 55 patients with T2 or T3N0N1 rectal cancer treated at a Danish tertiary cancer center with high dose CRT for 6 weeks (60 Gy in 30 fractions). They reported 73% of patients achieved a cCR and 15% of patients had regrowth at one year (9).

Despite such findings, there are no randomized control trials investigating watch-and-wait to date probably due to logistical obstacles. This makes the OnCoRe Project all the more relevant. The OnCoRe Project is the largest propensity-score matched cohort analysis study with 259 patients either meticulously observed or operatively managed after CRT (5). This analysis found no differences in 3-year overall survival or 3-year non-regrowth disease-free survival between watch-and-wait versus surgical resection. Patients managed under watch-and-wait had better 3-year colostomy-free survival than did those who had surgery (74% vs. 47%).

Our analysis revealed a dramatic polarization among US ROs regarding their views on watchful waiting. Just under half of the respondents support watchful waiting for patients with LARC who achieve a cCR after neoadjuvant CRT. Lack of adoption can at least be partially explained by almost half of our respondents citing insufficient clinical evidence for watch-and-wait. It is difficult to imagine a randomized trial in the United States for patients who achieve a cCR after neoadjuvant CT, as many patients may not choose to be randomized to immediate TME when they find out about the alternative option. Yet many organ-sparing treatments are done in the absence of randomized clinical evidence—such as treatment of anal cancer with the Nigro protocol (10) and bladder cancer with the tri-modality approach (11). In addition, there is a lack of a single reliable tool for assessing cCR (12), and a careful follow-up of these patients is essential to ascertain that a local regrowth could be promptly salvaged with TME so as to not jeopardize patient’s chance of cure.

We have limited our survey to practicing US ROs. The majority of watch-and-wait supporters felt comfortable discussing the watch-and-wait approach, with a significant portion preferring the conversation be initiated by other specialists. The fact that this conversation focuses on either omitting, deferring or undergoing surgery could explain why ROs avoid the topic. ROs who do not work in multidisciplinary teams with surgeons and medical oncologists may not feel comfortable initiating the conversation themselves. Respondents with a higher LARC patient load (more than 10 patients evaluated annually) were more likely to feel confident in initiating a conversation concerning wait-and-watch. The high-volume clinics may imply an established multidisciplinary team with a common treatment strategy.

Lack of confidence to initiate the discussion of watchful waiting after chemoradiation is not specific to ROs. Surgeons in Australasia are not confident in a conservative approach to cCR as there is a lack of reliable pathological criteria for pathologic complete response (pCR). When given a pathological interpretation of a resected specimen suggesting pCR, only 16.7% of Australasian surgeons felt comfortable equating the interpretation to no residual tumor cells in the specimen (12). Ongoing research is investigating the role of MRI and 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) preoperatively to define cCR, which could help inform the decision-making process at the outset of LARC management in the future (13).

Limitations

Low response rate is our study’s greatest limitation. It is likely that response bias could have influenced our results. Our survey was intended to be short and, therefore, did not capture granular information about knowledge of other trials or participation in multi-disciplinary clinics with rectal surgeons and medical oncologists.

Conclusions

This is the first analysis of contemporary views of practicing US ROs regarding a watchful waiting strategy for patients who a achieve cCR after neoadjuvant CRT. Our results suggest a dramatic polarization in practitioners’ attitudes, and amongst those who support this treatment paradigm, there was much division in the levels of comfort leading this discussion.

These results suggest a general equipoise toward watchful waiting on the level of practicing US ROs and are important for the design of future prospective clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

We thank the respondents who have taken the time to participate and complete our survey.

Funding: This work was support by OHSU REDCap (1 UL1 RR024140 01).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by institutional review board of Oregon Health and Science University (IRB protocol 11149), and the requirement to obtain informed consent from survey respondents was waived.

References

- Lynn PB, Strombom P, Garcia-Aguilar J. Organ-Preserving Strategies for the Management of Near-Complete Responses in Rectal Cancer after Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2017;30:395-403. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Nadalin W, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for stage 0 distal rectal cancer following chemoradiation therapy: long-term results. Ann Surg 2004;240:711-7; discussion 717-8. [PubMed]

- Yang TJ, Goodman KA. Predicting complete response: is there a role for non-operative management of rectal cancer? J Gastrointest Oncol 2015;6:241-6. [PubMed]

- Smith JJ, Chow OS, Gollub MJ, et al. Organ Preservation in Rectal Adenocarcinoma: a phase II randomized controlled trial evaluating 3-year disease-free survival in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated with chemoradiation plus induction or consolidation chemotherapy, and total mesorectal excision or nonoperative management. BMC Cancer 2015;15:767. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Renehan AG, Malcomson L, Emsley R, et al. Watch-and-wait approach versus surgical resection after chemoradiotherapy for patients with rectal cancer (the OnCoRe project): a propensity-score matched cohort analysis. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:174-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Habr-Gama A, Sabbaga J, Gama-Rodrigues J, et al. Watch and wait approach following extended neoadjuvant chemoradiation for distal rectal cancer: are we getting closer to anal cancer management? Dis Colon Rectum 2013;56:1109-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Proscurshim I, et al. Patterns of failure and survival for nonoperative treatment of stage c0 distal rectal cancer following neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:1319-28; discussion 1328-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanghera P, Wong DW, McConkey CC, et al. Chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer: an updated analysis of factors affecting pathological response. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2008;20:176-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Appelt AL, Pløen J, Harling H, et al. High-dose chemoradiotherapy and watchful waiting for distal rectal cancer: a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:919-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leichman L, Nigro N, Vaitkevicius VK, et al. Cancer of the anal canal. Model for preoperative adjuvant combined modality therapy. Am J Med 1985;78:211-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitin T. Radical Cystectomy is the best choice for most patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer? Opinion: No. Int Braz J Urol 2017;43:188-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Behrenbruch C, Ryan J, Lynch C, et al. Complete clinical response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer: an Australasian perspective. ANZ J Surg 2015;85:103-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fischkoff KN, Ruby JA, Guillem JG. Nonoperative approach to locally advanced rectal cancer after neoadjuvant combined modality therapy: challenges and opportunities from a surgical perspective. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2011;10:291-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]