Gender differences in health-related quality of life among patients with colorectal cancer

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the fourth leading cause of death related to cancer in the world (1,2). There is a geographical variation in the distribution of CRC worldwide; over two-thirds of incident cases of CRC and 60% of colorectal- related deaths occur in developed countries with western diet culture (1). Currently, the incidence of CRC has been increasing in many developing countries. Reports also indicated an increase in the incidence of CRC in Iran (3-6). Given, the widespread use of advanced screening techniques for the detection of CRC, the trend of cases diagnosed in the early stages, and therefore, the survival rate among CRC patients have increased (7-10). With the rapid advances in medical practices, the goal of health care providers is not only to increase survival time but also to improve the quality of life (QOL) of patients (11). CRC, as well as the consequence of its treatment, can be associated with adverse effects that may compromise the QOL of CRC survivors (12).

Several studies have demonstrated that CRC survivors, especially females and patients with a stoma, have a lower health-related quality of life (HRQOL) (13-15). Also, the rate of depression and suicidal thoughts are higher in females than in males (13). Moreover, some studies indicated that patients with CRC have more sexual problems, and female patients have more coping and adjustment problems than male patients (16). In addition, their physical activity and overall QOL are more affected than in men (17). Although the traditional outcomes such as tumour recurrence, complications and survival rates are of great importance, the assessment of HRQOL has become considered as an important outcome measure (17,18), and has also been used for establishing priorities for scarce health care resources (19,20). This study aimed to assess the gender-related differences in the QOL of CRC patients in Northwest of Iran.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Tabriz city, located in East Azerbaijan Province, Northwest of Iran.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria for sampling were as follows: (I) CRC patients regardless of cancer stage and treatment plans; (II) ages of 18 years and older; (III) residing in East Azerbaijan province; and (IV) patients referred to the referral hospitals of East Azerbaijan (i.e., Talegani, Emam Reza, Sina, Shahid Madani, and international hospitals) within the time frame of two years from 2014 to 2016. Exclusion criteria were having a history of other cancers and refusing to participate in the study. Participants were interviewed by two trained interviewers. In this study, the Persian version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30, version 3.0) questionnaires which had been validated before the study, was used. In the first part of the questionnaire, there were questions about demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, age, marital status, education, place of residence, occupation) as well as disease-related questions (i.e., stage of cancer, duration of having cancer after diagnosis, adjuvant therapy, co-morbidity).

Variable definition

Age was categorized into two categories of ≤50, and more than 50. Level of education was classified into illiterate and literate; occupation was categories into employed and unemployed (in-paid work or work less), and finally the place of residence categories as either urban or rural. Patients were also asked whether they experienced various co-morbid conditions like heart disease, hypertension, chronic low back pain, arthritis, stroke, osteoporosis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stomach, and intestinal pain.

Instrument

The EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3) is a 30-item instrument with a four-point scale, from “not at all” to “very much,” for items 1 to 28; and a seven-point scale for items 29 and 30 (21). The QLQ-C30 include five functional scales [physical (PF); emotional (EF); cognitive (CF); role (RF); and social functioning, (SF)], eight Symptom scales, a global health status/QoL scale, and the perceived financial impact (22-24). After estimating the mean scores of scales (i.e., raw score), scores were linearly transformed to a scale from 0 to 100; a high score for a functional scale and global health status/QOL indicates a high/healthy level of functioning and a high QOL. (Score 0–25: very weak; score 25–49: weak; score 50: moderate; score 51–75: moderate to good; score 75–100: very good). In contrast, a high score for a symptom scale indicates a high level of symptomatology/problems (23,25).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed for demographic and clinical features. To describe the QOL scores, we calculated the means and standard deviations. The comparison of the socio-demographic and clinical features between male and female was performed by Chi-squared test (χ2 test). To compare the mean scores of QOL scales between male and female, Student’s t-test was used. A multivariable analysis of gender differences for total and subdomains of QLQ-C30 mean scores, adjusting for demographic, socioeconomic and clinical variables, was performed using multiple linear regression models. A series of multiple linear regression models were used with the total score of HRQOL and its dimensions as the dependent variables, i.e., gender, socio-demographic information, clinical characteristics. The level of statistical significance was set to 0.05, and the statistical analysis was performed by SPSS version 18, software.

Results

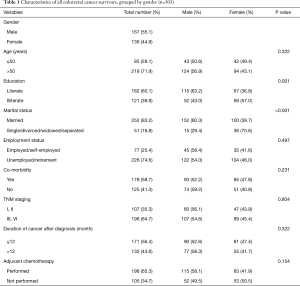

Overall 303 CRC survivors were included in this study. Of the 303 participants, 167 (55.1%) were male, and 136 (44.9%) were female. The mean age of participants was 58.16±13.58 years. The total characteristics of the study population and Gender differences in Clinic-epidemiological characteristics have been presented in Table 1.

Full table

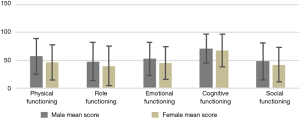

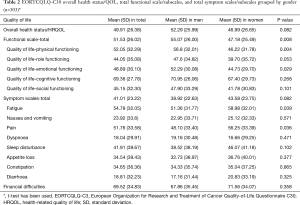

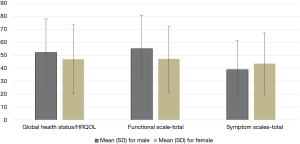

Table 2 shows the mean [standard deviation (SD)] score for the overall HRQOL score and its different dimensions which were grouped by gender. The mean score of overall HRQOL, functional and symptom scales in our population were 49.91, 51.53 and 41.01, respectively. The mean score of overall health status/HRQOL scale was higher in female than in male, but the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.082). Also, the mean score of the total functional scale was higher in females than in males, and the difference was statistically significant (P=0.008). The mean score of physical and emotional functioning subscales was statistically significant between females and males (P<0.05). Women had higher mean scores in all symptom’s subscales except dyspnoea, which means women with CRC have a high level of symptomatology or problems. Figure 1 shows the gender differences in the mean value of an overall HRQOL score, total functional scale, and total symptom scale. The functional subscale has been presented in Figure 2.

Full table

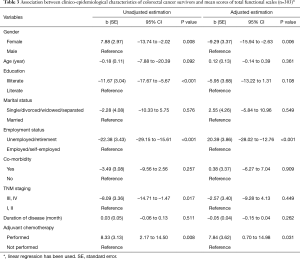

There was a statistically significant difference between men and women in the mean score of total Functional scale. Therefore, a univariate and multivariate linear regression modelling was also performed to assess the association between the clinical-epidemiological characteristics of patients and the score of the total functioning scale. Our findings demonstrated that there was a statistically significant association between the score of the total functioning scale, and gender, occupation, and adjuvant therapy. Among women and unemployed/retirement patients, the mean score of the total functioning scale was lower than in men and employed/self-employed patients (P<0.05). Patients who were receiving the adjuvant therapy had a higher mean score of total functioning scale (Table 3).

Full table

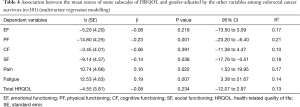

According to the results of multivariate linear regression, the physical (b=−14.80, P=0.001) and social functioning (b=−9.14, P=0.038) mean scores of women with CRC negatively more affected than men with CRC. In addition, women had a higher mean score in pain (b=10.74, P=0.022) and fatigue (b=12.53, P=0.007) symptom subscales in comparison to men (Table 4).

Full table

Discussion

In recent years, much attention has been focused on the impact of chronic diseases on the quality of life of patients. In addition to biochemical measures, taking into account the psychological, emotional, social, and financial issues in the evaluation of treatment, can play a significant role in achieving a positive patient outcome from both a physician’s and patient’s perspective (26). There are various questionnaires designed specifically for the measurement of quality life. The EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire is one of these questionnaires designed to evaluate the QOL of cancer patients (22,24). This study aimed to assess the HRQOL of 303 patients with CRC by using the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire as well as gender differences in the quality of life (GOL) of CRC survivors. According to our results, the mean scores of the overall QOL, total functional scale, and symptom scale were 49.91, 51.53 and 41.01, respectively; which were lower than the EORTC reference values (27). These lower scores for the QOL scales of our population may be partly explained by the advanced stage of the majority of our patients (65%); which require more complicated treatment processes and is also accompanied by more clinical symptoms. According to the results of the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), cancer survivors were significantly more likely to report poor HRQOL than adults without cancer (i.e., 24.5% vs. 10.2% for poor physical HRQOL and 10.1% vs. 5.9% for poor mental HRQOL) (28). CRC survivors in Akhondi-Meybodi et al. study (Yazd, Iran), had a higher mean score of HRQOL in comparison to our study population, and in contrast to our results, there was no significant relationship between gender and QOL (10). Although the demographic and clinical characteristics of both studies were similar, the reason for such a discrepancy is not clear. In the other studies the mean score of GOL of their patients has also been reported higher than our study population (20,29,30). In our study, role and social functioning of our patients were more negatively affected by CRC, and the cognitive function of patients was less affected by CRC.

For symptom subscales, our study population, both men and women, assigned the highest score to financial problems (mean score =69.52±34.83), and then to fatigue, pain, sleep, disturbance, constipation, loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, diarrhoea, and dyspnea, respectively. Our results close to the Mrabti et al. study (31). Our financial score is very high in comparison to the EORTC reference values for CRC patients (69.52±34.8 vs. 13.6±26.3) (27). Also, in the Abu-Health et al. study in Amman, the mean score for financial difficulties was lower (20.7%) than our score (32). Some reasons such as the high cost of cancer treatments, not having free health insurance for cancer treatment, loss of jobs due to health problems, and low socioeconomic status have been mentioned for financial difficulties (31,32). Women in our study reported lower HRQOL than men. Women also had a statistically significant lower score for the total functional scale, especially for its physical and emotional functioning subscales.

Based on the results of the multivariate linear regression analysis, women, workless patients or retirees, and those who have undergone adjuvant chemotherapy have a significantly worse functional score. These three factors, i.e., gender, occupation, and adjuvant therapy can be considered as the independent and robust predictive factors of GOL regarding the functional scale in our study population. In Abu-Helalah et al. study, cancer recurrence, resection and anastomosis surgery, radiation therapy, and stoma use have been reported as predictors of physical functioning (32). In Baider et al. study, male patients reported a better mental health status than female patients (33). The results of some other studies are consistent with those of the current study (34-36). Women may have a less tolerance threshold against physical and psychological stressors due to physiological reasons (33). Therefore, after the diagnosis of diseases, especially cancer, their morale will be more fragile than men. The other strong predictor of QOL in our study was occupation. Unemployment reduced the mean score of functional scale by 22, which is a high figure. Given the fact that patients with a full-time job or well- paid jobs are usually covered by insurance, after getting a disease, they experience less stress in comparison to those who are unemployed or who have part-time jobs. Studies have shown that people with lower income are more likely to have a lower QOL than people with higher income. Ramsey et al. in their study have shown that low income is significantly associated with poor outcomes in terms of physical, social and emotional dimensions of QOL scale (37).

Although the current study highlighted the gender differences of HRQOL in the northwest of Iran where the data on CRC outcomes is minimal, this study has some limitations. First, the generalizability of the study is questioned because the study population were patients presented at tertiary referral hospitals and therefore did not include patients in private hospitals or other hospitals. Secondly, it is possible that the stage of disease in our study population would be more advanced than other studies because the study population for the current study were selected from the referral hospitals which provide more professional clinical procedures and higher levels of care than other hospitals. The stage at presentation is a predictor of the HRQOL among cancer patients.

Conclusions

The results of the current study did support gender-specific differences in HRQOL among CRC survivors. The results showed that women had poorer performance in physical and social functioning and they reported more fatigue and pain than men. Therefore, it might be advisable to consider strategies to improve the HRQOL in women.

Acknowledgements

This study has been supported by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: This study received Ethics approval from the ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. All patients completed an informed consent form before the interview session.

References

- Arnold M, Sierra MS, Laversanne M, et al. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut 2017;66:683-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haggar FA, Boushey RP. Colorectal Cancer Epidemiology: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Risk Factors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2009;22:191-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marley AR, Nan H. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet 2016;7:105-14. [PubMed]

- Dolatkhah R, Somi MH, Bonyadi MJ, et al. Colorectal cancer in Iran: molecular epidemiology and screening strategies. J Cancer Epidemiol 2015;2015:643020. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amirkhah R, Naderi-Meshkin H, Mirahmadi M, et al. Cancer statistics in Iran: Towards finding priority for prevention and treatment. Cancer Press 2017;3:27-38. [Crossref]

- Hessami Arani S, Kerachian MA. Rising rates of colorectal cancer among younger Iranians: is diet to blame? Curr Oncol 2017;24:e131-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2016;315:2576-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Ali MU, Warren R, et al. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2016;15:298-313. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lieberman DA. Clinical practice. Screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1179-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akhondi-Meybodi M, Akhondi-Meybodi S, Vakili M, et al. Quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer in Iran. Arab J Gastroenterol 2016;17:127-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ai Zh P, Gao XL, Li JF, et al. Changing trends and influencing factors of the quality of life of chemotherapy patients with breast cancer. Chinese Nursing Research 2017;4:18-23. [Crossref]

- Bours MJ, van der Linden BW, Winkels RM, et al. Candidate Predictors of Health-Related Quality of Life of Colorectal Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. Oncologist 2016;21:433-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krouse R, Grant M, Ferrell B, et al. Quality of life outcomes in 599 cancer and non-cancer patients with colostomies. J Surg Res 2007;138:79-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tuinstra J, Hagedoorn M, Van Sonderen E, et al. Psychological distress in couples dealing with colorectal cancer: Gender and role differences and intracouple correspondence. Br J Health Psychol 2004;9:465-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nugent KP, Daniels P, Stewart B, et al. Quality of life in stoma patients. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:1569-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grant M, McMullen CK, Altschuler A, et al. Gender Differences in Quality of Life Among Long-Term Colorectal Cancer Survivors With Ostomies. Oncol Nurs Forum 2011;38:587-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmidt CE, Bestmann B, Küchler T, et al. Gender Differences in Quality of Life of Patients with Rectal Cancer. A Five-Year Prospective Study. World J Surg 2005;29:1630-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marventano S, Forjaz MJ, Grosso G, et al. Health related quality of life in colorectal cancer patients: state of the art. BMC Surgery 2013;13:S15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gordis L. Epidemiology, 5th ed. Chapter 4: The Occurrence of Disease: II. Mortality and Other Measures of Disease Impact. Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc., 2014:81-2.

- Näsvall P, Dahlstrand U, Löwenmark T, et al. Quality of life in patients with a permanent stoma after rectal cancer surgery. Qual Life Res 2017;26:55-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30:A Quality-of-Life Instrument for Use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology. J Nat Cancer Inst 1993;85:365-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Michelson H, Bolund C, Nilsson B, et al. Health-related Quality of Life Measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30. Acta Oncologica 2000;39:477-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kyriaki M, Eleni T, Efi P, et al. The EORTC core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30, version 3.0) in terminally ill cancer patients under palliative care: validity and reliability in a Hellenic sample. Int J Cancer 2001;94:135-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arraras JI, Vega FA, Tejedor M, et al. The EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3) Quality of Life Questionnaire:Validation study for Spain with head and neck cancer patients. Psychooncology 2002;11:249-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pastorino A, Di Bartolomeo M, Maiello E, et al. Aflibercept Plus FOLFIRI in the Real-life Setting: Safety and Quality of Life Data From the Italian Patient Cohort of the Aflibercept Safety and Quality-of-Life Program Study. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2018;17:e457-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Theofilou P. Quality of Life: Definition and Measurement. Eur J Psychol 2013;9:150-62. [Crossref]

- Scott NW, Fayers P, Aaronson NK, et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 Reference Values Manual. 2nd Edition. Brussels, Belgium: EORTC Quality of Life Group, 2008.

- Weaver KE, Forsythe LP, Reeve BB, et al. Mental and physical health-related quality of life among U.S. cancer survivors: population estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012;21:2108-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li X, Song X, Chen Z, et al. Quality of life in rectal cancer patients after radical surgery: a survey of Chinese patients. World J Surg Oncol 2014;12:161. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Engel J, Kerr J, Schlesinger-Raab A, et al. Quality of Life in Rectal Cancer Patients A Four-Year Prospective Study. Ann Surg 2003;238:203-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mrabti H, Amziren M, ElGhissassi I, et al. Quality of life of early stage colorectal cancer patients in Morocco. BMC Gastroenterology 2016;16:131. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abu-Helalah MA, Alshraideh HA, Al-Hanaqta MM, et al. Quality of Life and Psychological Well-Being of Colorectal Cancer Survivors in Jordan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:7653-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baider L, Bengel J. Cancer and the spouse: gender-related differences in dealing with health care and illness. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2001;40:115-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pucciarelli S, Del Bianco P, Toppan P, et al. Health-related quality of life outcomes in disease-free survivors of mid-low rectal cancer after curative surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:1846-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gray NM, Hall SJ, Browne S, et al. Campbell NC Modifiable and fixed factors predicting quality of life in people with colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2011;104:1697-703. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Momeni M, Ghanbari A, Joukar F, et al. Predictive Factors of Quality of Life in Patients with Colorectal cancer. Indian J Cancer 2014;51:550-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramsey SD, Andersen MR, Etzioni R, et al. Quality of life in survivors of colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 2000;88:1294-303. [Crossref] [PubMed]