Endoscopic and clinicopathological characteristics of gastrointestinal adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma

Introduction

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the most common extranodal site that is involved in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (1,2). Primary GI lymphomas are mainly composed of B-cells, and T/natural killer (NK)-cell neoplasia occurs rarely. In primary GI T-cell lymphomas, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) is considered to be a neoplasia of the T-intraepithelial lymphocytes (T-IELs), and it is divided into two groups based on the recent World Health Organization (WHO) classification (3,4). In Northern Europe and America, about 80% of patients had type I EATL, which is closely associated with celiac disease (5). Type II EATL, which is now called monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma (MEITL), is more prevalent in East Asia and has no correlation with celiac disease (6). Additionally, primary GI T/NK-cell lymphomas are reported to be mainly located in the small intestine and colon (7).

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) mainly consists of CD4+ T-cell neoplasms that are associated with long-standing human T-lymphotropic virus-1 (HTLV-1) infection (8). HTLV-1 is transmitted from mothers to infants through breastmilk (8,9). ATLL is characterized by a high tendency for leukemic changes and involves various organs, including the GI tract, liver, spleen, and skin (10). In a previous study, GI ATLL showed three typical endoscopic features: solitary or multiple tumor-forming-type lesions, superficial spreading-type lesions, and mucosal thickening-type lesions (11-13). We have previously demonstrated that GI ATLL as well as MEITL show high CD103 (αEβ7 integrin) homing receptor expression in T-IELs (31/56 patients, 55%) and ATLL had some characteristics that are similar to the histopathological features of MEITL (14). The current study reports differences in the clinical and endoscopic features of 61 GI tract lesions from 36 lymphoma- and 18 acute-type ATLL patients. Among these patients, we endoscopically demonstrated that gastropathy-, enteropathy-, and proctocolitis-like ATLL lesions were occasionally encountered characteristic features. Additionally, early clinical stages of Lugano’s classification, solitary tumor-forming lesions, and pleomorphic large tumor cells were better prognostic factors in GI ATLL patients. We discussed differences in endoscopic and clinicopathological findings among patients with GI ATLL and other types of primary GI lymphoma.

Methods

Patient selection and clinical findings

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the institutional review board at our hospital (Institutional review board approval number: 14-8-08). We retrospectively reviewed medical records and analyzed samples from ATLL patients at the Department of Pathology, Fukuoka University from 1990 to 2018. This study focused on 54 Japanese patients from whom 61 GI ATLL lesions were examined. We classified ATLL patients into clinical subgroups based on the Japanese Lymphoma Study Group classification (15). The clinical stage was classified based on the Lugano-modified Ann Arbor staging system (16). Histological classification was performed in accordance with the WHO classification that was proposed in 2017 (8).

Endoscopic examination

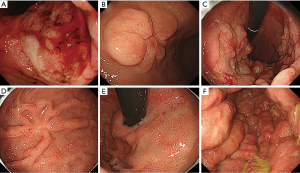

All 54 patients underwent endoscopic examination of the upper and/or lower GI tract. A video endoscope (Olympus Medical System, Tokyo, Japan) was used for all endoscopic examinations. The endoscopic images or records were reviewed retrospectively by two experienced endoscopists (H.I. and Y.K.). Biopsy specimens for histologic examination were taken from the stomach and/or small intestine and/or colon using standard biopsy forceps. Endoscopic findings for GI ATLL were classified into five types, based on a previous classification (13,14) with modifications, as follows: (I) solitary tumor-forming-type lesion (including solitary ulcerated and/or elevated tumor (Figure 1A,B), and submucosal tumor-like lesion); (II) multiple tumor-forming-type lesion (including multiple ulcerated and/or elevated tumors (Figure 1C) or multiple lymphomatous polypoid lesions); (III) superficial spreading-type lesion [including early gastric cancer-like lesion (Figure 1D)]; (IV) gastropathy-like (gastritis-like) lesion (Figure 1E) and enteropathy-like lesions (enteritis-like or proctocolitis-like lesions); and (V) mucosal thickening-type lesions (large thickening of folds; Figure 1F).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

We performed a histologic examination of biopsy specimens from 43 ATLL patients, surgical specimens from ten patients with GI tract involvement, and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) from one patient. We examined three main histologic findings because ATLL has similar features as EATL (14). In non-neoplastic mucosal layers, >30 small IELs per 100 epithelial cells was considered to be a significant increase. Scattered small IELs without irregular nuclei were considered to be reactive, and medium-sized or large atypical lymphocytes with irregular swollen nuclei were defined as neoplastic IELs. For immunohistology, monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies were applied to formalin-fixed tumor samples using a Leica BondMax automated stainer (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). Immunostaining of CD3 (PS1; Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK), CD4 (4B12, Leica Biosystems), CD8 (C81/44B, Leica Biosystems), CD25 (4C9; Leica Biosystems), CD30 (BerH2, DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark), CD103 (EPR41662, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and CD194 [chemokine receptor (CCR) 4, 1G1, BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA] was performed after antigen retrieval. Samples in which more than 30% of the tumor cells were labeled with a particular antibody marker were classified as positive. Histological findings were reviewed by two pathologists (M.T. and S.N.).

Statistical analysis

Clinicopathological data were analyzed using the Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. A value of P<0.05 was considered significant. Overall survival (OS) curves for all patients were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method and analyzed using the log-rank test.

Results

Patient characteristics

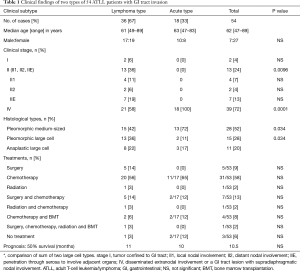

The clinical features of 54 ATLL patients with GI tract invasion are summarized in Table 1. Thirty-six patients (67%) were classified as having lymphoma-type and 18 patients (33%) were classified as having acute-type lesions. The median patient age at diagnosis was 62 years (range, 47–89 years), and 2 patients (4%) were stage I, 13 (24%) were stage II, and 39 (72%) were stage IV. The 15 patients (28%) at stage I or II all had lymphoma-type lesions. Among them, 6 patients (11%) at stages I and II1 showed primary GI ATLL (stomach, 4; small intestine, 2). Twenty-one patients with lymphoma-type lesions (58%) and 18 patients with acute-type lesions (100%) were classified as stage IV, which was significantly different between the two groups (P=0.0001). Gastrectomy, jejunectomy, and ileotomy were performed to remove the main tumor in 5 patients (9%), while 31 patients (57%) received chemotherapy and 5 (10%) underwent bone marrow transplantation (BMT) after surgery and chemotherapy. Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (CHOP) therapy was administered to 25 patients, and mogamulizumab therapy was administered to three patients. All six primary GI ATLL patients were treated by gastrectomy or jejunectomy with subsequent combination chemotherapy or BMT.

Full table

Histological and immunohistochemical findings

For tumor cell features, 28 patients (52%) had pleomorphic medium-sized lymphoma, 15 patients (28%) had pleomorphic large cell lymphoma, and 11 patients (20%) had CD30-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Three (two in lymphoma-type and one in acute type) of the examined 22 ATLL patients (14%) showed an increase in reactive IELs in the overlying epithelium and epithelial glands outside the tumors. Nineteen (12 in lymphoma-type and 7 in acute type) of the examined 46 patients (41%) showed small nests of tumorous IELs in the epithelial glands and covering the superficial epithelium. Lymphoma cells in all 54 patients (100%) were CD3+, 40 (74%) were CD4+, and nine (17%) were CD8+; 44 patients (100%) were CD25+, 13 of 41 patients (32%) were CD30+, and 24 of 31 patients (77%) were CD194 (CCR4+). Among the 54 ATLL patients with GI tract involvement, 26 (48%) were CD103+. Seventeen of 36 lymphoma-type patients (47%) and nine of 18 acute-type patients (50%) were CD103+.

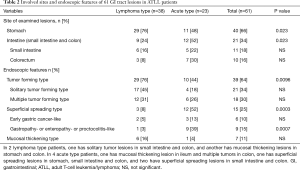

Lesions and endoscopic features

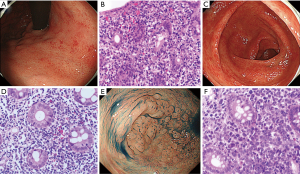

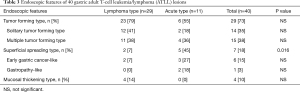

The sites involved and endoscopic features of 61 GI ATLL lesions in acute and lymphoma-type ATLL patients are summarized in Table 2. Gastric ATLL lesions were present in 40 lesions (66%) and intestinal lesions were present in 21 lesions (34%). Among these, small intestinal ATLL lesions were present in 11 lesions (18%) and colorectal lesions were present in 10 lesions (16%). Significantly more gastric ATLL lesions were found in 29 of 38 lymphoma-type lesions (76%) compared with 11 of 23 acute-type lesions (48%; P=0.023). Small intestinal and colorectal ATLL lesions were significantly more frequent in 12 of 23 acute-type lesions (52%) compared with 9 of 38 lymphoma-type lesions (24%; P=0.023). The tumor-forming type (solitary and multiple tumor-forming types) was significantly more frequent in 29 of 38 lymphoma-type ATLL lesions (76%) compared with ten of 23 acute-type lesions (44%; P=0.0096). The superficial spreading type was significantly more frequent in 12 of 23 acute-type ATLL lesions (52%) compared with three of 38 lymphoma-type lesions (8%; P=0.0003). In the superficial spreading type, gastropathy-, enteropathy-, or proctocolitis-like lesions showing reddish and mildly edematous mucosa were significantly more frequent in acute-type lesions (9 of 23, 39%) compared with lymphoma-type lesions (1 of 38, 3%; P=0.0007). The endoscopic and pathological features of gastropathy- and proctocolitis-like lesions in acute-type ATLL are shown in Figure 2.

Full table

The endoscopic features of 40 gastric lesions are summarized in Table 3. The tumor-forming type was found in 23 of 29 lymphoma-type ATLL lesions (79%) and 6 of 11 acute-type lesions (55%). Even in gastric lesions, the superficial spreading-type ATLL was significantly more frequent in 5 of 11 acute-type ATLL lesions (45%) compared with 2 of 29 lymphoma-type lesions (7%; P=0.016). Gastropathy, including gastritis- and gastric erosion-like lesions, were present in 2 of 11 lesions (18%) in gastric acute-type ATLL. The endoscopic features of 21 intestinal lesions are summarized in Table 4. The tumor-forming type was present in 6 of 9 lymphoma-type ATLL lesions (67%) and in 4 of 12 acute-type lesions (33%). The superficial spreading-type lesion was present in 7 of 12 acute-type lesions (58%) and in 1 of 9 lymphoma-type lesions (11%). All three enteropathy-like lesions were present in the superficial spreading-type of acute-type ATLL. Proctocolitis-like lesions were present in four superficial spreading lesions of the acute-type and one of the lymphoma-type lesions.

Full table

Full table

Relationship between endoscopic features and tumor cell size

Tumor-forming-type tumors were composed of predominantly pleomorphic or anaplastic large cell lymphoma in 23 of 39 lesions (59%), which was significantly more frequent compared with that of the superficial spreading-type lesions (2 of 15, 13%; P=0.007). The superficial spreading-type tumors were mainly composed of pleomorphic medium-sized cell lymphoma in 13 of 15 lesions (87%), which was significantly more frequent compared with 16 of 39 tumor-forming-type tumors (41%; P=0.007). Mucosal thickening-type tumors were mainly composed of pleomorphic medium-sized cell lymphoma in six of seven lesions (86%).

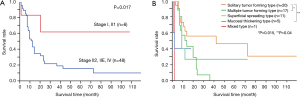

Analysis of patient prognosis

Lymphoma and acute-type ATLL patients showed a progressive clinical course, and 50% OS was observed at 11 and 10 months, respectively. The 50% OS of six patients with primary GI ATLL in the early stages (I and II1) was over 110 months, and these patients showed a significantly better prognosis than that of 48 advanced patients at other stages (P=0.017; Figure 3A). Twenty patients having solitary tumor-forming-type ATLL lesions showed significantly better OS compared with 17 multiple tumor-forming-type (P=0.015) and five mucosal-thickening-type lesions (P=0.04), but not 11 superficial spreading-type lesions (P=0.38; Figure 3B). Sites involved in the GI tract showed no prognostic factors in any of the ATLL patients. Histologically, 26 patients with pleomorphic or anaplastic large cell ATLL showed a significantly better prognosis compared with 28 patients with pleomorphic medium-sized ATLL (P=0.034).

Discussion

The incidence of ATLL invasion in the stomach and intestine was 29% and 25%, respectively, in an autopsy study (17). In the current study, ATLL invasion of the stomach, small intestine, and colon was found in 66%, 18%, and 16% of patients, respectively. Gastric invasion by ATLL was significantly higher than those of other types of primary GI T-cell lymphoma and CD56+ and EBV+ NK/T-cell lymphoma, which mainly involved the small intestine and colon (7,18). Additionally, gastric ATLL lesions were significantly more frequent in lymphoma-type lesions (29 of 38 lesions, 76%) compared with acute-type lesions (11 of 23, 48%; P=0.023). Small intestinal and colonic ATLL lesions were significantly greater in acute-type lesions (12 of 23 lesions, 52%) compared with lymphoma-type lesions (9 of 38, 24%; P=0.023). We demonstrated that ATLL significantly involved the stomach and leukemic behavior had a large influence on the GI sites that were involved.

Iwashita et al. reported 40 GI tract lesions from 27 ATLL patients, which were endoscopically classified into the solitary tumor-forming type (2 lesions, 5%), multiple elevated type (15, 37.5%), superficial spreading type (9, 22.5%), mucosal thickening type (4, 10%), and mixed type (10, 25%) (13). Among these, multiple elevated-type lesions were mostly seen in lymphoma-type patients (9 of 19 lesions, 47%). Additionally, superficial spreading-type lesions were frequently found in acute-type ATLL patients (7 of 21 lesions, 33%). Utsunomiya et al. also reported an endoscopic study of five acute-type ATLL patients showing diffusely spreading gastric and colonic mucosal lesions with erosion, multiple small nodules, and mucosal thickening (11). In the current study, the tumor-forming type was mainly present in lymphoma-type ATLL lesions (29 of 38 lesions, 76%) and the superficial spreading type was mainly found in acute-type lesions (12 of 23, 52%), both of which were statistically significant (P=0.0096, P=0.0003). Additionally, 23 of 39 tumor-forming type-lesions (59%) were composed of pleomorphic or anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and 13 of 15 superficial spreading-type lesions (87%) were composed of pleomorphic medium-sized cells (P=0.007). In 20 patients with HTLV-1 negative primary gastric T-cell lymphoma, Kamamoto et al. demonstrated that 13 large cell lymphoma patients (65%) mainly showed tumor formation by lymphoma cells with frequent CD30 expression, and two of the remaining seven medium-sized lymphomas showed a superficial spreading tumor with enteropathy-like features (19). This suggested that endoscopic types of the GI ATLL were largely influenced by leukemic behavior and the ATLL tumor cell size.

Over 80% of MEITL patients showed the intramucosal spreading of lymphoma cells with preserved glands and neoplastic CD103+ and CD8+ IELs in and beside the main tumors (20). CD103 is also expressed on subsets of CD4+ regulatory T-cells in the peripheral blood and dendritic cells of the GI tract (21). The frequent expression of CD103 and histological features of GI ATLL suggested that ATLL had the characteristics of T-IELs or mucosal T-cells or their neoplasias (14). The endoscopic features of MEITL were reported as edematous mucosa with mosaic and diffuse thickening patterns and shallow ulceration as well as ulcerative tumors in the small intestine (22). Additionally, EATL also shows mucosal flattening, thickening, and ulcerating lesions as well as multiple tumor formations (23). In the current study, superficial spreading lesions were significantly more frequent in 12 of 23 acute-type ATLL lesions (52%) compared with three of 38 lymphoma-type lesions (8%; P=0.0003). We found distinct features of gastropathy-like lesions in two of 11 gastric acute-type ATLL (18%) and enteropathy-like lesions in three of 12 intestinal acute-type lesions (25%), which had similar endoscopic and histological features as those of MEITL and EATL; these are rarely reported in ATLL (24). Additionally, we identified features of proctocolitis-like lesions in four of 12 intestinal acute-type ATLL lesions (33%), which were rarely seen even in MEITL patients (25). Endoscopically, it is necessary to recognize gastropathy-, enteropathy-, and proctocolitis-like lesions in GI ATLL.

The current study reported six lymphoma-type patients (11%) who were thought to have primary GI ATLL. Tanaka et al. summarized 15 previously reported patients with primary gastric ATLL in clinical stages I and II1 (26). Among these patients, eight showed an aggressive clinical course and three showed long-term remission from 50 to 132 months. In the current study, six patients with primary GI ATLL showed a significantly better prognosis compared with those of 48 patients in more advanced stages of the disease (P=0.017). Further study is necessary to clarify the clinicopathological findings and appropriate treatments for patients with primary GI ATLL.

Endoscopically, ATLL patients with solitary tumor-forming-type lesions showed a significantly better OS compared with those with multiple tumor-forming- and mucosal thickening-types (P=0.015, P=0.04). Sakata et al. only demonstrated that five acute-type ATLL patients with gastric lesions had a significantly worse prognosis compared with 15 acute-type ATLL patients without gastric involvement (P<0.05) (12). In 73 primary gastric DLBCL patients, lesions that were more than 30 mm in diameter and more than 11 mm deep, as assessed endoscopically, were significantly worse prognostic factors (P=0.01 and 0.039, respectively), as were patients diagnosed at clinical stages greater than IIE and those with multiple gastric lesions (P<0.01 and 0.034, respectively) (27). Endoscopic tumor growth patterns indicated no prognostic factors even in patients with primary GI T/NK-cell lymphoma and DLBCL (7,18,27). We demonstrated that solitary tumor-forming-type lesions were mainly found in lymphoma-type ATLL patients and patients with this type of lesion had a better prognosis compared with the other endoscopic lesion types.

Self-limited and indolent T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) of the GI tract are rarely reported. Matnani et al. summarized that indolent CD4-positive, CD8-positive and both negative T-cell LPDs of the GI tract showed various endoscopic features including nodules, polypoid lesions, fissures, superficial ulcers, erosions, and normal mucosa (28). Superficial spreading-type lesions including gastroenteropathy-like lesions often found in the indolent T/NK-cell LPDs patients were also characteristic in GI ATLL. We found increased reactive T-IELs in three of 22 non-neoplastic ATLL lesions (14%), which are frequently found in celiac disease and non-neoplastic mucosa of EATL (3). To detect the prodromal and early ATLL lesions, it is necessary to examine how persistent HTLV-1 infection influences T-IELs and mucosal lymphocytes in the GI tract.

Conclusions

GI T/NK-cell lymphoma frequently involves the small intestine and colon. ATLL predominantly involves the stomach. Leukemic behavior of ATLL had a large influence on tumor location and endoscopic features of GI tract lesions. Gastroenteropathy- and proctocolitis-like lesions were additional characteristic features of the GI ATLL lesions. Patients with primary GI ATLL in the early clinical stages were occasionally found and showed a rather prolonged clinical course. Additionally, solitary tumor-forming-type lesions and large tumor cells were better prognostic factors. It is important to recognize the patient’s clinical stage and endoscopic features of GI ATLL.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Tomoko Fukushige and Tomomi Okabe for their excellent technical assistance. We thank Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding: Supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research © (No.17K08732) from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: This study was approved by institutional review board of Fukuoka University Hospital (No. 14-8-08) and all consent requirement was met based on the institutional policy for retrospective study.

References

- Groves FD, Linet MS, Travis LB, et al. Cancer surveillance series: non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma incidence by histologic subtype in the United States from 1978 through 1995. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1240-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shi Z, Ding H, Shen QW, et al. The clinical manifestation, survival outcome and predictive prognostic factors of 137 patients with primary gastrointestinal lymphoma (PGIL). Medicine 2018;97:e9583. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhagat G, Jaffe ES, Chott A, et al. Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. WHO classification of tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. Lyon: LARC Press, 2017:372-7.

- Jaffe ES, Chott A, Ott G, et al. Monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma. WHO classification of tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. Lyon: LARC Press, 2017:377-8.

- Deleeuw RJ, Zettl A, Klinker E, et al. Whole-genome analysis and HLA genotyping of enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma reveals 2 distinct lymphoma subtypes. Gastroenterology 2007;132:1902-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takeshita M, Nakamura S, Kikuma K, et al. Pathological and immunohistological findings and genetic aberrations of intestinal enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma in Japan. Histopathology 2011;58:395-407. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim DH, Lee D, Kim JW, et al. Endoscopic and clinical analysis of primary T-cell lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract according to pathological subtype. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:934-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohshima K, Jaffe ES, Yoshino T, Siebert R. Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. WHO classification of tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, 4th ed. Lyon: LARC Press, 2017:363-7.

- Hino S, Sugiyama H, Doi H, et al. Breaking the cycle of HTLV-1 transmission via carrier mother’s milk. Lancet 1987;2:158-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Uchiyama T, Ishikawa T, Imura A. Adhesion properties of adult T cell leukemia cells. Leuk Lymphoma 1995;16:407-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Utsunomiya A, Hanada S, Terada A, et al. Adult T-cell leukemia with leukemia cell infiltration into the gastrointestinal tract. Cancer 1988;61:824-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sakata H, Fujimoto K, Iwakiri R, et al. Gastric lesions in 76 patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Cancer 1996;78:396-402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iwashita I, Uike N, Nishiyama K, et al. Characteristics of gastrointestinal tract lesions in a representative immunodeficiency state – ATLL. Stomach and Intestine 2005;40:1151-71. (English summary).

- Ishibashi H, Nimura S, Ishitsuka K, et al. High expression of intestinal homing receptor CD103 in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, similar to 2 other CD8+ T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:462-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shimoyama M. Diagnostic criteria and classification of clinical subtypes of adult T-cell leukaemia-lymphoma. A report from the Lymphoma Study Group (1984-87). Br J Haematol 1991;79:428-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rohatiner A, d’Amore F, Coiffier B, et al. Report on a workshop convened to discuss the pathological and standing classification of gastrointestinal tract lymphoma. Ann Oncol 1994;5:397-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sato E, Hasui K, Tokunaga M. Autopsy findings of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Gann Mono Cancer Res 1982;28:51-64.

- Jiang M, Chen X, Yi Z, et al. Prognostic characteristics of gastrointestinal tract NK/T-cell lymphoma. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:e74-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kawamoto K, Nakamura S, Iwashita A, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of primary gastric T-cell lymphoma. Histopathology 2009;55:641-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tse E, Gill H, Kim SJ, et al. Type II enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: a multicenter analysis from the Asia Lymphoma Study Group. Am J Hematol 2012;87:663-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gunnlaugsdottir B, Maggadottir SM, Skaftadottir I, et al. The ex vivo induction of human CD103+ CD25hi Foxp3+ CD4+ and CD8+ Tregs is IL-2 and TGF-β1 dependent. Scand J Immunol 2013;77:125-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hong YS, Woo YS, Park G, et al. Endoscopic Findings of Enteropathy-Associated T-Cell Lymphoma Type II: A Case Series. Gut Liver 2016;10:147-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van de Water JM, Cillessen SA, Visser OJ, et al. Enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma and its precursor lesions. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2010;24:43-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Isomoto H, Furusu M, Onizuka Y, et al. Colonic involvement by adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma mimicking ulcerative colitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;58:805-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ishibashi H, Nimura S, Kayashima Y, et al. Multiple lesions gastrointestinal tract invasion by monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma, accompanied by duodenal and intestinal enteropathy-like lesions and microscopic lymphocytic proctocolitis: a case series. Diagn Pathol 2016;11:66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tanaka K, Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, et al. Long-term remission of primary gastric T cell lymphoma associated with human T lymphotropic virus type 1: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Intern Med 2007;46:1783-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu YZ, Xue K, Wang BS, et al. The size and depth of lesions measured by endoscopic ultrasonography are novel prognostic factors of primary gastric diffuse large B-cell Lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2019;60:934-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matnani R, Ganapathi KA, Lewis SK, et al. Indolent T- and NK-cell lymphoproliferative disorders of the gastrointestinal tract: a review and update. Hematol Oncol 2017;35:3-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]