Addressing sexual dysfunction in colorectal cancer survivorship care

Introduction

Sexual dysfunction is one of the most common long-term effects of colorectal cancer treatment, yet studies consistently show that this issue is rarely discussed among patients and their providers (1). Colorectal cancer survivorship has increased significantly in recent years due to advances in surgical techniques and adjuvant therapy, and the majority of colorectal patients will become long-term cancer survivors (2). Increasing survival rates in colorectal cancer have shifted the focus of patient health care needs from treating malignancies to addressing survivors’ long-term quality of life, which includes sexual functioning (1). When sexual issues are not addressed, it can have a significant negative impact on the quality of life of survivors (3). To improve the quality of survivorship care in colorectal cancer, the sexual health needs of patients require assessment and treatment at all stages of care (4-6).

Sexuality is an important component of quality of life, given that the majority of colorectal cancer survivors will remain sexually active following treatment (7). Changes in sexual functioning in colorectal cancer survivors can affect not only patients, but their partners as well (1). Although colorectal cancer survivors often report that their overall quality of life (QOL) is good, both men and women report significant problems with sexual functioning following treatment (6,8-11).

Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in colorectal cancer survivors

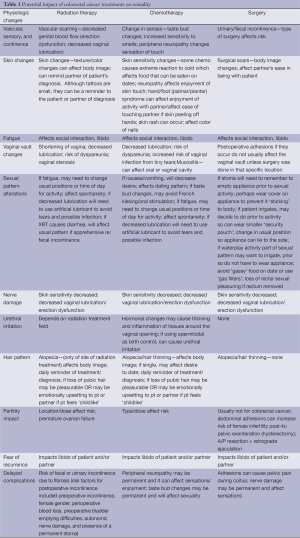

Forty-one percent of all cancer survivors experience a decrease in sexual functioning and 52% experience changes in body image (12). In patients with colorectal cancer, the rates of sexual dysfunction can be even higher given the physiological changes that can result from surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy (Table 1). For example, patients who have undergone surgery for rectal cancer are significantly less likely to be sexually active than prior to surgery, and their sexual problems can be complex and multi-factorial (4). The type of surgery can impact sexual function as well. For example, one study found that women who had abdominoperineal excision (n=73) for rectal cancer were less sexually active, had less frequent coitus, and were less likely to achieve arousal or orgasm than women who had anterior resection (n=222) (13). In males, one study found that total mesorectal surgery (n=49) affected erection (80%) and ejaculation (82%), while another study by Sartori and colleagues found less impact on erection and ejaculation (n=35) (14,15). Other studies have found that stoma creation does not always negatively impact on sexual function. For example, the meta-analysis by Ho, Lee, Stein and Temple found mixed results in terms of the relationship between stomas and sexual dysfunction. Despite the lack of conclusive evidence, the authors recommended that patients be informed that surgery might affect sexual functioning (6).

Full table

Sexual dysfunction in colorectal cancer survivors can also be related to medications (e.g., hormonal treatment or psychotropic medications) or changes in body weight during the course of treatment (16-19) (Table 1). Prior sexual history, age, partner status, socioeconomic status, cultural beliefs surrounding sexuality, global quality of life and comorbid medical conditions can all have an impact on sexual functioning in survivors (20). Any symptoms of sexual dysfunction can also be exacerbated by symptoms of anxiety, depression, and fatigue which are common among survivors of cancer (21).

Although there is evidence to suggest that high rates of sexual dysfunction are reported among colorectal cancer survivors, very few studies have compared the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in this population with normative control groups. One of the few recent comparative studies of colorectal cancer survivors with a normative sample reported that male survivors of rectal cancer experienced higher rates of erectile dysfunction (54%) than those with colon cancer (25%) or those within the normative sample (27%) (4). Males with rectal cancer also reported higher rates of ejaculation problems (68% rectal versus 47% of colon cancer survivors). Female rectal and colon cancer survivors reported significantly more vaginal dryness (35% rectal; 28% colon) than the normative population (5%) and pain during intercourse (30% rectal; 9% colon; 0% normative) (4).

Patient-provider communication about sexual dysfunction

Providing education, informational support, and treatment options can help to improve sexual functioning in colorectal survivors (11). Despite the high prevalence of sexual dysfunction reported by colorectal cancer survivors and increasing awareness of the sexual health needs of patients, sexual functioning is often not adequately addressed by health care providers (22,23). Patients often express reluctance to raise sexual issues during appointments, and many report feeling embarrassed or ashamed to ask questions related to sexual health (24). Discussing sexual issues may be a new experience for many cancer patients who may not have felt the need to address this topic with health care providers in the past (25,26). This can result in patients feeling unsure how to broach and describe sexual issues for the first time. Health care providers may also be reluctant to discuss sexual functioning due to time limitations, lack of knowledge regarding treatment for sexual problems, and beliefs about the appropriateness of discussing sexuality within the context of cancer treatment (1).

Recent studies have identified issues related to patient-provider communication for patients with many types of cancer, including colorectal cancer. For example, Flynn and colleagues found that in a survey of 819 patients with cancer and cancer survivors, 78% of participants felt that it was important to discuss how cancer may impact sexual functioning and 64% believed that it was helpful to include partners in discussions with providers about their sex life (5). However, only 29% of participants reported that they had asked their health care provider about problems with their sex life, and 45% reported that they had never received any information from their providers about how cancer or cancer treatment may affect their sexual functioning. Although most patients (59%) who did not ask their providers about sexual problems reported that they did not have any questions, 21% felt that the problems with their sex life were “not bad enough” to discuss, and 9% reported that they felt too shy or embarrassed to bring up the topic. Focus group participants in that study reported that it would be helpful for the oncology provider to initiate discussions about sexual problems (5).

A recent qualitative study of patients (n=21), their partners (n=9), and their health care providers (n=10) assessed sexual health needs for colorectal cancer survivors from their perspective (1). This study sought to identify potential barriers and facilitating factors to communication about sexual functioning through a combination of focus groups and questionnaires. As with the Flynn et al. study, participants in this study were not always able to recall if they had received information about sexual functioning after treatment. Patient/partner knowledge about the availability of treatment for sexual problems was also limited (1). The patients and partners noted that having more information about potential sexual problems and heath care options may have facilitated further discussion about sexual functioning with their health care providers. The patients and partners also noted that they felt embarrassed to bring up sexuality with their providers, and many felt that it was inappropriate to discuss sexual problems if the treatment goal was patient survival.

Traa and colleagues reported that health care providers identified a number of barriers to providing adequate sexual health care including knowledge and competence in the area of sexuality, beliefs about sexuality, and attitudes towards discussing sexuality (1). In the Traa et al. study, most providers noted that they did not feel sufficiently prepared to have detailed discussions about sexuality or did not consider it to be within the scope of their care. Health care providers echoed some of the same concerns expressed by patients/partners by noting that as providers they felt it was inappropriate to discuss sexuality if the main treatment goal was survival. They also expressed concern that the potential for causing discomfort or embarrassment for the patient and/or their family members might have an adverse effect on overall treatment.

Additionally, sexuality may be considered “irrelevant” for certain patients due to their age, gender, or relationship status (1,10). For example, health care providers may consider elderly or widowed patients as having less sexual health care needs. This is similar to prior studies of communication regarding sexuality in primary care settings that have identified cultural factors (e.g., gender, age, race/ethnicity, or sexual orientation differences) as barriers to openly discussing sexual functioning (22).

Improving communication about sexual dysfunction in survivorship care

Given the high rate of reported sexual dysfunction among colorectal cancer survivors and the limited patient-provider communication about sexual functioning in oncology settings, there is a need to address barriers to sexual functioning discussions in order to improve the quality of life aspect of survivorship care. Althof & Parish have identified a number of patient-centered communication skills that may help providers to improve interactions regarding sexual functioning, while taking into consideration the time constraints of appointment time (24). For example, using a combination of clinical interview and questionnaire techniques can help to screen for potential sexual problems, gather information about patients’ sexual functioning, and help patients to feel more comfortable addressing questions about sexual functioning with their provider (24).

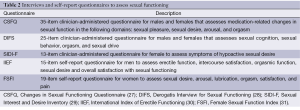

A number of assessment tools related to sexuality have been developed that can help providers to gather data about sexual functioning quickly prior to meeting with patients (Table 2). Although self-report questionnaires are not sufficient to fully evaluate a patient’s symptoms of sexual dysfunction, they can provide a useful way to begin conversations about sexuality. Often survivors who have not brought up sexual issue concerns with providers will disclose those concerns on a self-report symptom list (22). Using open-ended questions to help patients to elaborate on their sexual functioning concerns can help to clarify sexual problems and identify potential areas for treatment. Open-ended questions can be particularly helpful in eliciting information about how sexual problems are impacting patient functioning (24).

Full table

Overall, sexual dysfunction is prevalent among colorectal cancer survivors and an important aspect of quality of life for health care providers to consider. Despite patients’ report of the importance of discussing sexuality with their providers, it is often not addressed during appointments. In order to improve patient-provider communication regarding sexual functioning, the following recommendations may be helpful to consider:

Recommendations for providers:

- “As part of clinical practice, screening and assessment of sexual functioning should be included early in treatment for all patients and continue during all stages of care” (22). Regardless of age, sexual orientation, or partner status, sexual functioning is an important aspect of the quality of life for all patients that should be made part of clinical practice with assessments being done frequently and continuing during all stages of treatment. As recommended by Althof & Parish, a combination of physical examination, clinical interview, and questionnaires may help to improve assessment, engage patients in a conversation that they may be reluctant to initiate, and, as appropriate, elicit patient concerns (24). Even if patients do not report changes in sexual functioning after treatment has been completed, it is important to re-assess the patients as they may experience delayed onset of sexual problems after treatment or develop new problems over time;

- “Patients may be reluctant to raise the topic of sexual functioning during appointments. Initiating conversations about sexual functioning as part of standard clinical care can help to facilitate discussions about these issues”. Patients consistently state that they feel more comfortable if providers bring up the topic of sexual functioning (5). Asking permission to discuss sexuality may help patients to feel more comfortable answering questions about their current functioning and provide them with language to help them describe and report their symptoms. Involving sexual partners in these discussions (with patient permission) may also help to facilitate a more open dialogue among patients, partners, and providers throughout treatment;

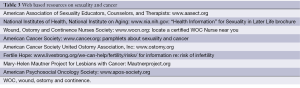

- “Maintain referral resources and information regarding treatment options for sexual dysfunction for patients and their partners”. Health care providers report that lack of knowledge about treatment options and concerns about treating sexual dysfunction within their scope of practice may limit their ability to discuss these issues with patients (1). In multidisciplinary care settings, it may be possible to consult with another provider with expertise in sexual functioning in the event that a practitioner’s knowledge and skill sets are limited in this area (32). If these options for referral are not available, being aware of local external referral sources for treatment of sexual dysfunction can also facilitate further treatment for patients. There are also a number of patient resources that may provider valuable information about sexual dysfunction and help patients to make informed decisions about seeking treatment for sexual problems (Table 3).

Full table

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The views expressed in this abstract/manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the US Government.

References

- Traa MJ, De Vries J, Roukema JA, et al. The sexual health care needs after colorectal cancer: the view of patients, partners, and health care professionals. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:763-72. [PubMed]

- van Steenbergen LN, Lemmens VE, Louwman MJ, et al. Increasing incidence and decreasing mortality of colorectal cancer due to marked cohort effects in southern Netherlands. Eur J Cancer Prev 2009;18:145-52. [PubMed]

- Mercadante S, Vitrano V, Catania V. Sexual issues in early and late stage cancer: a review. Support Care Cancer 2010;18:659-65. [PubMed]

- Den Oudsten BL, Traa MJ, Thong MS, et al. Higher prevalence of sexual dysfunction in colon and rectal cancer survivors compared with the normative population: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:3161-70. [PubMed]

- Flynn KE, Reese JB, Jeffery DD, et al. Patient experiences with communication about sex during and after treatment for cancer. Psychooncology 2012;21:594-601. [PubMed]

- Ho VP, Lee Y, Stein SL, et al. Sexual function after treatment for rectal cancer: a review. Dis Colon Rectum 2011;54:113-25. [PubMed]

- Lange MM, Marijnen CA, Maas CP, et al. Risk factors for sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer treatment. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1578-88. [PubMed]

- Kasparek MS, Hassan I, Cima RR, et al. Long-term quality of life and sexual and urinary function after abdominoperineal resection for distal rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2012;55:147-54. [PubMed]

- Orsini RG, Thong MS, van de Poll-Franse LV, et al. Quality of life of older rectal cancer patients is not impaired by a permanent stoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2013;39:164-70. [PubMed]

- Temple LK. Erectile dysfunction after treatment for colorectal cancer. BMJ 2011;343:d6366. [PubMed]

- Traa MJ, De Vries J, Roukema JA, et al. Sexual (dys) function and the quality of sexual life in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 2012;23:19-27. [PubMed]

- Zebrack BJ, Foley S, Wittmann D, et al. Sexual functioning in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology 2010;19:814-22. [PubMed]

- Tekkis PP, Cornish JA, Remzi FH, et al. Measuring sexual and urinary outcomes in women after rectal cancer excision. Dis Colon Rectum 2009;52:46-54. [PubMed]

- Nishizawa Y, Ito M, Saito N, et al. Male sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 2011;26:1541-8. [PubMed]

- Sartori CA, Sartori A, Vigna S, et al. Urinary and sexual disorders after laparoscopic TME for rectal cancer in males. J Gastrointest Surg 2011;15:637-43. [PubMed]

- Reese JB. Coping with sexual concerns after cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 2011;23:313-21. [PubMed]

- Breukink SO, Donovan KA. Physical and psychological effects of treatment on sexual functioning in colorectal cancer survivors. J Sex Med 2013;10 Suppl 1:74-83. [PubMed]

- Bruheim K, Guren MG, Dahl AA, et al. Sexual function in males after radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;76:1012-7. [PubMed]

- Bruheim K, Tveit KM, Skovlund E, et al. Sexual function in females after radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Acta Oncol 2010;49:826-32. [PubMed]

- Milbury K, Cohen L, Jenkins R, et al. The association between psychosocial and medical factors with long-term sexual dysfunction after treatment for colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:793-802. [PubMed]

- Tuinman MA, Hoekstra HJ, Vidrine DJ, et al. Sexual function, depressive symptoms and marital status in nonseminoma testicular cancer patients: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology 2010;19:238-47. [PubMed]

- Bober SL, Varela VS. Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: challenges and intervention. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3712-9. [PubMed]

- Park ER, Norris RL, Bober SL. Sexual health communication during cancer care: barriers and recommendations. Cancer J 2009;15:74-7. [PubMed]

- Althof SE, Parish SJ. Clinical interviewing techniques and sexuality questionnaires for male and female cancer patients. J Sex Med 2013;10 Suppl 1:35-42. [PubMed]

- Klaeson K, Sandell K, Berterö CM. To feel like an outsider: focus group discussions regarding the influence on sexuality caused by breast cancer treatment. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2011;20:728-37. [PubMed]

- Sekse RJ, Raaheim M, Blaaka G, et al. Life beyond cancer: women’s experiences 5 years after treatment for gynaecological cancer. Scand J Caring Sci 2010;24:799-807. [PubMed]

- Clayton AH, McGarvey EL, Clavet GJ, et al. Comparison of sexual functioning in clinical and nonclinical populations using the Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (CSFQ). Psychopharmacol Bull 1997;33:747-53. [PubMed]

- Meston CM, Derogatis LR. Validated instruments for assessing female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther 2002;28 Suppl 1:155-64. [PubMed]

- Clayton AH, Segraves RT, Leiblum S, et al. Reliability and validity of the Sexual Interest and Desire Inventory-Female (SIDI-F), a scale designed to measure severity of female hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Marital Ther 2006;32:115-35. [PubMed]

- Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, et al. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology 1997;49:822-30. [PubMed]

- Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther 2000;26:191-208. [PubMed]

- Dowswell G, Ismail T, Greenfield S, et al. Men’s experience of erectile dysfunction after treatment for colorectal cancer: qualitative interview study. BMJ 2011;343:d5824. [PubMed]