A curious discourse of Krukenberg tumor: a case report

Introduction

In the year 1896 Krukenberg presented five cases of peculiar ovarian tumor having appearance of malignant cells as new type of primary ovarian sarcomas which he named “fibrosarcoma ovarii mucocellulare (carcinomatodes)” (1,2). In his thesis he proposed it as a primary tumor of ovary, but latter it was proved to be nearly always secondary to gastrointestinal (GI) tract malignancy particularly stomach (3). However, there have been rare and isolated cases which have been interpreted as primary tumors. Other primary GI organs responsible are colon, biliary system, jejunum, and pancreas. Non GI organs like breast, uterine endometrium, thyroid, kidney and lungs are also found to be of primary malignancy rarely (4). Nearly 80% cases are bilateral. Histologically these are usually poorly differentiated intestinal type adenocarcinoma with or without signet ring cells, sometimes producing mucins (5). It is considered as a metastatic disease with very poor prognosis. Till date optimal treatment has not been established, and it is still uncertain whether surgical resection of ovarian metastases and/or the primary could help. We report a rare presentation of gastric carcinoma with ovarian metastasis with particular importance to its management decision.

Case report

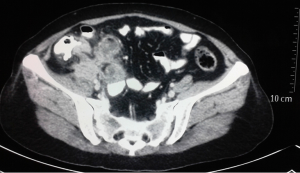

A 48-year-old house wife presented with dull aching pain in right lower abdomen for last one month. Pain was initially periumbilical, but shifted to right lower abdomen within 24 hours of onset. It was associated with nausea, vomiting and profound anorexia. Ultrasound abdomen done initially revealed ill-defined complex mass lesion of 7.25 cm × 5.69 cm in right iliac fossa. Complete blood count showed leucocytosis (14,900/cumm) with neutrophilia (90%). Contrast enhanced CT abdomen (Figure 1) revealed ill defined heterogeneous poorly enhancing mass lesion of 9.7 cm × 7 cm size in right iliac fossa with perilesional fat stranding, aggregation of terminal ileal loops and non-visualisation of appendix. She was treated conservatively with antibiotis and analgesics, improved symptomatically within one week with return of appetite but a persistently low grade dull aching pain in right lower abdomen.

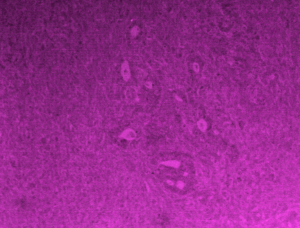

She came to our department with the said illness. Detailed history and review of previous investigations revealed a rare condition. To start with around 2 years and 6 months back she suffered from dull aching pain lower abdomen with feeling of lower abdominal heaviness associated with dyspeptic symptoms, anorexia and weight loss. Ultrasound abdomen at that point revealed solid heterogeneous 9 cm × 7.2 cm adnexal mass lesion with scattered anechoic areas within, 7.5 cm × 6.6 cm left ovarian cyst and 3.83 cm × 3.73 cm hypoechoic area in left adnexa, all being separated from uterus, urinary bladder and bowel loops with no evidence of ascites. CA-125 was 130.6 U/mL. She was diagnosed to have bilateral adnexal mass in peri-menopausal age group and planned for total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy without any further investigations in some outside hospital. On exploration, as per operation note, left sided ovarian unilocular cystic lesion and right ovary replaced by solid mass with cystic areas and ruptured nodular capsule were detected with mild ascites and normal liver. Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAH + BSO) was performed. Patients recovered uneventfully. Ascitic fluid cytology showed no malignant cells. Operative histopathology revealed normal uterus with proliferative endometrium, benign cystadenoma of left ovary and moderately differentiated mucinous intestinal type adenocarcinoma of right ovary with focal signet ring cells (Figure 2). With the suspicion of primary GI malignancy upper GI endoscopy was performed, which revealed 4 cm × 4 cm ulcerated lesion along lesser curvature of stomach. Histopathology of biopsy specimen confirmed signet ring cell adenocarcinoma of mixed diffuse and intestinal type with extensive intestinal metaplasia, invading lamina propria. Immunohistochemistry was positive for pancytokeratin AE1/AE3 and CDX2. A diagnosis of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma with Krukenberg tumour was made and six 3-weekly cycles of palliative chemotherapy given with aprecap, cisplatin and capecitabine. After completion of chemotherapy patient gained weight and appetite, she was on regular follow up.

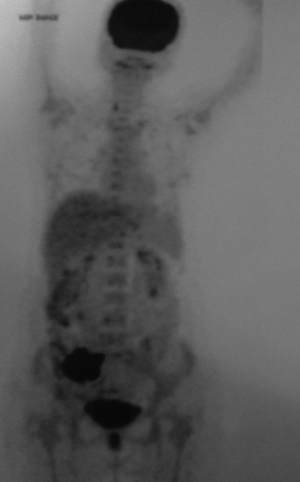

Two years after the completion of chemotherapy she came to our department with dull aching pain right lower abdomen with mass lesion at right iliac fossa. In our institution she got upper GI endoscopy done to see a 2 cm × 2 cm indurated lesion on lesser curvature of stomach with ulceration. Endoscopic biopsy revealed poorly differentiated gastric adenocarcinoma, grade IV. 18-FDG PET with 64 slice CT abdomens showed ill defined heterogeneously enhancing soft tissue lesion of 6 cm × 5.3 cm × 5.6 cm sizes with pockets of air and fluid in right iliac fossa and thickened, dilated appendix. Right iliac fossa mass was FDG avid (SUVmax 22.0) but not the gastric lesion (Figure 3). PET-CT suggested a hypermetabolic inflammatory appendicular mass with regression of its size and surrounding inflammation in comparison to previous CT scan. On admission her haemoglobin was 11.6 gm% and leucocyte count 8,400/cumm. Liver and renal functions were normal. A working diagnosis was settled as resolving complicated acute appendicitis with signet ring cell gastric adenocarcinoma and synchronous ovarian metastasis status TAH + BSO status 6 cycle completed cytotoxic palliative chemotherapy. She was decided for diagnostic laparoscopy and appendectomy. As the progression free survival of gastric carcinoma with ovarian metastasis after TAH + BSO and palliative chemotherapy crossed 2 years a decision for palliative gastrectomy was proposed if there would be no stigmata of disseminated disease. Diagnostic laparoscopy revealed no metastatic disease stigmata and a contained appendicular perforation with inflammatory mass formation in right iliac fossa. Laparotomy followed by appendecectomy and distal subtotal gastrectomy were performed (Figure 4). Patients recovered well in postoperative period. Operative histopathology reported as poorly differentiated gastric adenocarcinoma infiltrating the wall and extending to serosal fat with two metastatic nodes out of eight perigastric lymph nodes and xanthogranulomatous appendicitis with periappendiceal inflammation. She has been advised for palliative chemotherapy by Medical Oncology Department and discharged on 6th postoperative day.

Discussion

Krukenberg tumors constitute 1% to 2% of all ovarian neoplasms, usually presented in younger female with average age of 45 years (3,6). Most of the cases originate from gastric adenocarcinoma. Majority of cases they are synchronous, but 20% to 30% occur as metachronous lesion after removal of primary. The route of spread of this tumor is still not well established. As the tumor is usually well encapsulated and rarely shows any ovarian surface involvement, theory of peritoneal seeding from primary lesion is questioned. Rich lymphatics draining gastric mucosa and submucosa initiating retrograde lymphatic spread to ovary is mostly accepted theory. Few authors favour theory of hematogenous spread through thoracic duct (7). The prognosis of a patient with Krukenberg tumor is extremely poor with average survival time between 3 and 10 months. Only 10% of patients survive more than two years after diagnosis (8). Treatment of patients with Krukenberg tumor is controversial. Some studies have investigated the role of removing Krukenberg tumor originated from stomach and demonstrated that resection of ovarian metastases might prolong survival (9). Some other studies suggested that metachronous ovarian metastases or unilateral ovarian metastases might correlate with good survival and ovarian metastasectomy may be beneficial when gross residual diseases being thoroughly eradicated (10). In a retrograde analysis of 133 patients with Krukenberg tumor author concluded ovarian metastasectomy might be helpful for prolonging the survival of some patients with Krukenberg tumor originated from stomach. Patients without ascites, and with resected primary gastric cancer lesion could get benefit from and be potential candidate for surgical treatment. They did not recommend patients to undergo ovarian metastasectomy if the primary stomach lesion hadn’t or couldn’t been resected, or ascites was detected (5).

Our patient was originally a case of gastric adenocarcinoma with synchronous Krukenberg tumor. Here patients underwent removal of ovarian lesion without the knowledge of having a gastric lesion. After the histopathology had come as moderately differentiated mucinous intestinal type adenocarcinoma of right ovary with focal signet ring cells she was further investigated to have signet ring cell gastric adenocarcinoma. Possibly thinking it to be metastatic disease with poor outcome she was offered palliative chemotherapy. And as nearly after 2 years 6 months of previous surgery she presented with complicated acute appendicitis necessitating surgical exploration, without any features of tumor dissemination other than persistent gastric tumor she was operated for appendectomy and palliative subtotal gastrectomy. There is no specific guideline for treating Krukenberg tumor, but existent literature favours operative removal of Krukenberg tumor along with primary tumor if there is no other dissemination.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Krukenberg, Friedrich: Uber das Fibrosarcoma ovarii mucocellulare (Carcinomatoides). Arch. f. Gynak., 50, 287-321, I896.

- Kim SH, Kim WH, Park KJ, et al. CT and MR findings of Krukenberg tumors: comparison with primary ovarian tumors. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1996;20:393-8. [PubMed]

- Al-Agha OM, Nicastri AD. An in-depth look at Krukenberg tumor: an overview. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006;130:1725-30. [PubMed]

- Lash RH, Hart WR. Intestinal adenocarcinomas metastatic to the ovaries. A clinicopathologic evaluation of 22 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1987;11:114-21. [PubMed]

- Peng W, Hua RX, Jiang R, et al. Surgical treatment for patients with Krukenberg tumor of stomach origin: clinical outcome and prognostic factors analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e68227. [PubMed]

- Young RH. From krukenberg to today: the ever present problems posed by metastatic tumors in the ovary: part I. Historical perspective, general principles, mucinous tumors including the krukenberg tumor. Adv Anat Pathol 2006;13:205-27. [PubMed]

- Taylor AE, Nicolson VM, Cunningham D. Ovarian metastases from primary gastrointestinal malignancies: the Royal Marsden Hospital experience and implications for adjuvant treatment. Br J Cancer 1995;71:92-6. [PubMed]

- Yook JH, Oh ST, Kim BS. Clinical prognostic factors for ovarian metastasis in women with gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology 2007;54:955-9. [PubMed]

- McGill FM, Ritter DB, Rickard CS, et al. Krukenberg tumors: can management be improved? Gynecol Obstet Invest 1999;48:61-5. [PubMed]

- Jun SY, Park JK. Metachronous ovarian metastases following resection of the primary gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer 2011;11:31-7. [PubMed]