|

Case Report

Coexistence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour and colorectal

adenocarcinoma: Two case reports

Kinshuk Kumar1, Corwyn Rowsell2, Calvin Law3, Yoo-Joung Ko1

11Division of Medical Oncology, Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; 2Division of Surgical Pathology, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; 3Division of Surgical Oncology, Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Corresponding to: Yoo-Joung Ko, MD. Division of Medical Oncology, University of Toronto, Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre, 2075 Bayview Avenue, Toronto, ON M4N 3M5, Canada. Tel: 416-480-6100 ext 5847; Fax: 416-480-6002. Email: yoo-joung.ko@sunnybrook.ca.

|

|

Abstract

This paper reports two rare cases of patients with synchronous gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) and colorectal adenocarcinoma (CRC) where adjuvant FOLFOX chemotherapy was administered concurrently with imatinib mesylate. The first case is a 67-year-old woman with a large gastrointestinal stromal tumour with metastasis masking a co-existing primary colon cancer, which was diagnosed after tumour response to imatinib mesylate. The second case presents a 61-year-old male with a primary colon cancer and a suspected metastatic lymph node, later confirmed to be a co-existing primary gastric GIST during colon surgery. While colorectal cancer is the third most common cause of cancer-related death in North America, the prevalence of GISTs remains rare. To date, very few cases of synchronous GIST and CRC adenocarcinoma have been reported in the literature. Although the coexistence of these two tumour types is rare, it is important to be aware of their disease patterns.

Key words

colonic neoplasms, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, neoplasms, multiple primary

J Gastrointest Oncol 2011; 2: 50-54. DOI: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2010.029

|

|

Case 1

In the fall of 2008, a previously well 67-year-old Caucasian

woman, presented with progressive fatigue over three

months accompanied by left lower abdominal pain. She

reported passage of “darker stools”; however, there was

no complaint of bright red blood per rectum or change in

stool shape. On physical examination, a minimally tender

palpable mass in the left lower quadrant was noted.

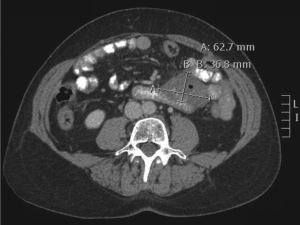

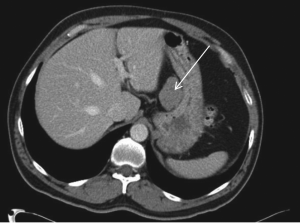

Computed tomography (CT) scan imaging revealed a

large abdominal mass (Fig 1) with multiple hypervascular

masses in the liver (Fig 2). The abdominal mass, with a

large area of internal necrosis, was intimately related to

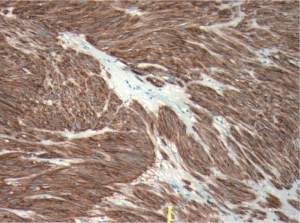

the jejunum with minimal small bowel dilatation. One of the liver lesions in segment 4b was biopsied under

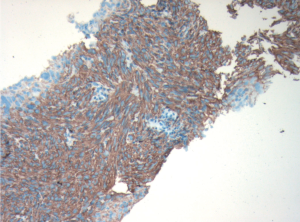

ultrasound guidance. Pathology revealed a spindle cell

tumour, which was strongly positive for CD117 and CD34

by immunohistochemistry (Fig 3). There were no mitotic

figures noted. The pathologic diagnosis was consistent

with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumour and in

December 2008, she was started on 400 mg of imatinib

mesylate per day.

Subsequently, follow-up CT imaging revealed significant

reduction of her primary GIST (Fig 4) as well as in the

hepatic metastases. The GIST decreased from its initial

size of 13.5 x 8.7 cm in November 2008 to 9.0 x 6.0 cm in

January 2009. The primary tumour continued to decrease

in size from 6.3 x 3.7 cm in June 2009 to 5.2 x 3.5 cm in

November 2009.

The CT scan in November 2009 revealed the presence

of a colonic mass with mesenteric lymphadenopathy.

The presence of the newly identified mass was confirmed

on colonoscopy, which revea led the presence of an

intraluminal mass at 80 cm from the anal verge. Biopsy of

this lesion revealed an invasive, moderately differentiated

adenocarcinoma of colonic origin.

After discussion at tumor board, a decision was made

to resect the primary colonic mass as well as the primary GIST. In December 2009, the patient underwent a left

hemicolectomy in addition to resection of the primary

GIST, which originated in the small bowel. The pathology

of the colonic mass revealed a moderately differentiated

adenocarcinoma with 7 out 12 lymph nodes involved.

The small bowel pathology revealed a spindle cell lesion

consistent with a GIST, which was positive for CD117 and

CD34. The Ki67 stain showed positivity in less than 1% of

tumour cells. The mitotic count was less than 1 per 50 High

Power Fields (HPF). The tumour showed large hypocellular

areas of hyalinization, an area of necrosis, and several areas

of hemorrhage as well as a focal hemangiopericytoma-like

pattern, consistent with treatment (imatinib mesylate)

effect. Of note, the laboratory findings did not include a preoperative

CEA, however, a CEA level was drawn shortly

after the surgery, measuring 2.5 ug/L.

She subsequently received 12 cycles of modif ied

FOLFOX-6 chemotherapy while remaining on imatinib for

her metastatic GIST. She did not experience any unexpected

toxicity from either the imatinib or chemotherapy and

remains well with continued regression of her liver

metastasis (GIST).

|

|

Case 2

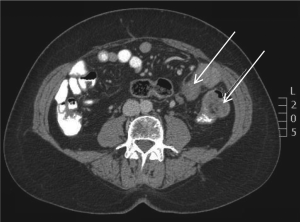

A 61-year-old Caucasian gentleman presented with a change

in bowel habits and rectal bleeding in March 2009. He

reported no associated anorexia or weight loss. Colonoscopy

and biopsy revealed an adenocarcinoma at the splenic

flexure. A staging CT scan also revealed a few subcentimeter

lymph nodes and a 5 cm mass at the gastrohepatic ligament

also suspected to be an enlarged metastatic lymph node (Fig

5).

In May 2009, at the time of surgery, the gastrohepatic

mass was resected. Once confirmed on a frozen section to

be a spindle cell tumour consistent with a GIST, a partial

gastrectomy was performed.

During the same operation, the patient also underwent a

left hemicolectomy. Final pathology revealed a 4 x 3.5 x 1.1

cm moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with 4/22

lymph nodes being positive.

The gastric-based mass was a primary GIST measuring

5.5 cm. Histopathological examination revealed a spindle

cell lesion with a high mitotic index of 7 mitoses per 50 high

power fields (HPF) with negative resection margins. The

immunohistochemistry was positive for CD34 and CD117

(Fig 6) and negative for S100 and desmin. Ki67 stained 10%

of tumor cell nuclei. A pre-operative CEA level was normal

at 1.3 ug/L.

Post-operatively, he received 10 cycles of adjuvant

FOLFOX chemotherapy for his stage III colon cancer as

well as one year of adjuvant imatinib therapy for the GIST.

Imatinib (400 mg per day) was started after he had received

two cycles of modified FOLFOX-6.

|

|

Discussion

Defined as cellular spindle cell, epithelioid, or pleomorphic

mesenchymal tumour of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract,

the term gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) was

introduced by Mazur and Clark in 1983 to differentiate

GISTs from leiomyomas ( 1, 2). The putative origin of these

tumours is believed to be the interstitial cells of Cajal, the

GI pacemaker cells ( 2-4). Approximately 95% of GISTs are

positive for expression of the KIT (CD117, stem cell factor

receptor) protein and as well as 70-80% of GISTs expressing CD34, the human progenitor cell antigen ( 2, 5). Although GISTs are the most common mesenchymal

tumours of the digestive tract, they remain rare. They

represent 0.1-3% of all GI cancers and have an incidence

of 10-20 cases/million ( 2, 4). Conversely, colorectal cancer

is the third most common cause of cancer-related death in

North America ( 6). While the incidence of synchronous

occurrence of other tumours with GISTs is on the rise,

there is no evidence of a common etiology ( 4, 7). Based on

the prevalence of both tumours, an incidental occurrence is

more likely. What remains important, however, is the need

to be aware of their coexistence. The first case outlines the presentation of a metastatic

small bowel GIST masking a colonic adenocarcinoma.

As the primary GIST decreased in size in response to

treatment with imatinib mesylate, the colonic mass and

enlarged mesenteric lymph node was unmasked. As lymph

node involvement with GIST is rare, the lymphadenopathy

was consistent with metastasis from a second primary

tumour. It also highlights that metastatic GIST should not

preclude the potential curative treatment of other secondary

cancers. The second case details a man with a primary

colonic neoplasm and an unidentified gastrohepatic mass

that was initially suspected to be a metastatic node but later confirmed to be a GIST. Given the atypical location of the

suspected lymph node, the patient underwent primary

surgery rather than systemic therapy. These cases highlight

the importance of being aware of second primary cancers

throughout the course of treatment for both colon cancer

and GISTs.

GISTs are most commonly found in the stomach

and small intestine. The coexistence of GISTs and

adenocarcinoma at two separate locations in the GI tract

is uncommon ( 7). Both colon cancer and GISTs are

infrequently associated with a genetic disposition and in

this report, neither patient reported a family history of any

malignancies. Surgery is the primary treatment modality for both

nonmetastatic GISTs and colon cancer ( 3). For metastatic

GIST, imatinib mesylate is the standard first-line treatment

( 8). Imatinib mesylate, a selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor,

has been shown to have a tumor response rate of greater

than 50% ( 3, 9). Continuous treatment with imatinib in the

metastatic setting is the standard treatment as interruptions

have been shown to result in rapid disease progression

( 10). Although surgery for patients with metastatic disease

is considered investigational, if the patient has disease

responsive to imatinib, surgical excision of a primary

tumor or an isolated metastasis that has progressed can be

associated with a good outcome ( 11). Treatment with imatinib in the adjuvant setting,

however, is now established as the standard of care for

those with resected primary GISTs ( 8). A phase III trial,

ACOSOG Z9001, was the first to demonstrate that one year

of imatinib as compared to placebo in the adjuvant setting,

is effective in decreasing recurrences. The trial included

713 patients with a resected GIST measuring at least 3 cm

in maximal diameter. Mitotic count was not an inclusion

criterion for this study. In this report, patient two had a

tumour greater than 3 cm and received adjuvant imatinib

therapy for one year consistent with the recommendations

of the major cancer societies ( 12, 13). Although adjuvant

imatinib is recommended for a minimum of one year, the

optimal duration of administration remains unknown.

The Intergroup EORTC 62024 trial is a randomized study

comparing two years of imatinib versus observation alone.

The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group (SSG) trial XVIII

is investigating three years versus one year of adjuvant

imatinib. Although both studies have completed accrual,

the results have not yet been presented. Hence, until the

results of these two studies are known, the recommended

duration of adjuvant treatment remains one year. A unique feature common to the two cases presented

is the concurrent treatment of adjuvant FOLFOX

chemotherapy with imatinib mesylate. Dexamethasone is a steroid that is commonly included as part of the antiemetic

regimen with a serotonin 5HT-3 antagonist in the

FOLFOX regimen. Both imatinib and dexamethasone are

metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) isoenzyme

CYP3A4. Imatinib is a potent competitive inhibitor of the

CYP450 isoenzyme CYP3A4 while dexamethasone is an

inducer ( 14). There is a high possibility of a drug interaction

as the plasma concentration of imatinib may decrease when

administered with dexamethasone. While case two presents

a patient who received concurrent treatment for ten cycles

of FOLFOX, the patient in case one was administered

concurrent treatment for all twelve cycles. Although there

were no ill effects noted in either case, perhaps due to

the brief exposure of both dexamethasone and imatinib,

a more prolonged exposure of the two medications may

benefit from possible monitoring of plasma imatinib

levels especially in the setting of metastatic GIST (case

one). Modif ications to the treatment could include

increasing the dosage of imatinib, decreasing the dosage of

dexamethasone, or administering another anti-emetic in

lieu of dexamethasone.

|

|

Conclusion

There have been very few incidences of synchronous

colorectal cancer and GISTs reported in literature. Most of

the cases described were found due to other malignancies

or discovered incidentally during surgery ( 3, 5, 15). The two

cases presented above underline the importance of being

aware of this particular coexistence as well as the unlikely

metastatic spread of GIST to lymph nodes, development

of other primary tumours during treatment of metastatic

GIST, and the importance of a multidisciplinary approach

to cancer treatment.

|

|

References

- Mazur MT, Clark HB. Gastr ic stroma l tumors. Reappraisa l of

histogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol 1983;7:507-19.[LinkOut]

- Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors--definition,

clinical, histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic

features and differential diagnosis. Virchows Arch 2001;438:1-12.[LinkOut]

- Melis M, Choi EA, Anders R, Christiansen P, Fichera A. Synchronous

colorectal adenocarcinoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST).

Int J Colorectal Dis 2007;22:109-14.[LinkOut]

- Efstathios P, Athanasios P, Papaconstantinou I, Alexandros P, Frangisca

S, Sotirios G, et al. Coexistence of gastrointestinal stromal tumor

(GIST) and colorectal adenocarcinoma: A case report. World J Surg

Oncol 2007;5:96.[LinkOut]

- Kosmidis C, Efthimiadis C, Levva S, Anthimidis G, Baka S, Grigoriou

M, et al. Synchronous colorectal adenocarcinoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumor in meckel's diverticulum; an unusual association. World

J Surg Oncol 2009;7:33.[LinkOut]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J

Clin 2010;60:277-300.[LinkOut]

- Gopal SV, Langcake ME, Johnston E, Salisbury EL. Synchronous

association of small bowel stromal tumour with colonic

adenocarcinoma. ANZ J Surg 2008;78:827-8.[LinkOut]

- DeMatteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, Maki RG, Pisters PW,

Demetri GD, et al. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of

localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised,

double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2009;373:1097-104.[LinkOut]

- Spinelli GP, Miele E, Tomao F, Rossi L, Pasciuti G, Zullo A, et

al. The synchronous occurrence of squamous cell carcinoma and

gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) at esophageal site. World J Surg

Oncol 2008;6:116.[LinkOut]

- Le Cesne A, Ray-Coquard I, Bin Bui N, Adenis A, Rios M, Duffaud

F, et al. Time to onset of progression after imatinib interruption

and outcome of patients with advanced GIST: Results of the BFR14 prospective french sarcoma group randomized phase III trial [abstract].

J Clin Oncol 2010; s28:10033.

- Mussi C, Ronellenfitsch U, Jakob J, Tamborini E, Reichardt P, Casali

PG, et al. Post-imatinib surgery in advanced/metastatic GIST: Is it

worthwhile in all patients? Ann Oncol 2010;21:403-8.[LinkOut]

- Nccn.org [Internet]. Washington: National Comprehensive Cancer

Network. c2010 [cited 2010]. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/.[LinkOut]

- Casa li PG, Jost L, Reichardt P, Schlemmer M, Blay JY, ESMO

Guidelines Working Group. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO

clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann

Oncol 2009;20:s64-7.[LinkOut]

- Scripture CD, Figg WD. Drug interactions in cancer therapy. Nat Rev

Cancer 2006;6:546-58.[LinkOut]

- Tzilves D, Moschos J, Paikos D, Tagarakis G, Pilpilidis I, Soufleris K,

et al. Synchronous occurrence of a primary colon adenocarcinoma and

a gastric stromal tumor. A case report. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol

2008;54:101-3.[LinkOut]

Cite this article as:

Kumar K, Rowsell C, Law C, Ko Y. Coexistence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour and colorectal

adenocarcinoma: Two case reports. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;2(1):50-54. DOI:10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2010.029

|