“This is not me”: patient, family, cultural and clinician considerations in cases of severe cancer-related debility

Dr. Viny: A 45-year-old female emergency room nurse with a history of sarcoidosis and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity experienced 2 months of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. The patient was initially evaluated in another hospital in the northeastern United States where she underwent an exploratory laparotomy that demonstrated evidence of colonic microperforation. During surgery, the patient underwent lysis of adhesions, transverse colon resection, and an omental biopsy. Preliminary pathologic analysis at the local treating institution from the colon and omental biopsy was deemed consistent with a primary epithelial ovarian cancer. The patient’s hospital course was further complicated by development of a jejunal stricture ultimately requiring a draining gastrostomy tube. The patient was transferred to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) for further management with pathology review at MSKCC concluding that the above specimens were instead consistent with adenocarcinoma of either upper gastrointestinal, pancreaticobiliary, or appendiceal primary location.

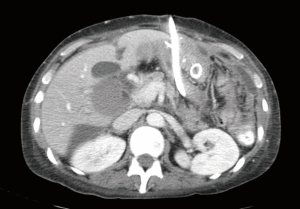

Upon consulting on the patient, she appeared chronically ill, cachectic and mostly bed bound, with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 3 (1). On physical examination, she had diminished bowel sounds and a markedly distended, diffusely tender abdomen with a G-tube and an intestinal ostomy in place. Computed tomographic (CT) imaging was obtained at MSKCC.

Dr. Haydar: My review of the CT scan showed mild thickening of multiple small bowel loops as well as loculated ascites throughout the abdomen with peritoneal infiltration, likely reflecting peritoneal carcinomatosis (Figure 1). A stent extending from the gastrojejunostomy into the proximal jejunum was stenotic in its mid-portion, likely causing proximal obstruction.

Dr Epstein: The patient was insistent to receive what she called “active treatment” and her family actually placed a note on her hospital room door stating, “Do not talk about the cancer not being treated; talk about how it will be treated”.

Dr. Abou-Alfa: When you say “insistent”, I assume you had told the patient your impression that she was too ill, and that you therefore did not recommend cancer therapy. Is this how it all started?

Dr. Epstein: Indeed, such essentially were our initial recommendations after meeting her and seeing her degree of unfortunately significant debility from the medical situation of widespread gastrointestinal exocrine cancer. Being largely bed-confined, we indicated that risk of treatment of the cancer itself would outweigh any potential for benefit of chemotherapy, and so that was one of the things that prompted the patient and her family’s repeated requests, and ultimately prompted this note on the hospital room door, as an additional continued request for cancer treatment.

Dr. Naghy: It appears the patient has an obstructing tumor in the jejunum, is there any role for palliative resection of the tumor?

Dr. Epstein: This was indeed considered. Multiple teams, including various surgical services and the gastroenterology team were involved to evaluate if resection of obstruction points could be considered with the goal of palliation. The gastrointestinal surgery team was originally consulted by the inpatient team, and the patient herself requested a specific liver surgeon to also be consulted. We believed there to be no role for liver surgery but in order to try to build a therapeutic relationship with the family, we did obtain that additional opinion. The liver surgeon also agreed there was no role for liver surgery. Unfortunately, all teams ultimately agreed that resection of either the primary or metastatic sites of the tumor were not possible, particularly given the patient’s poor performance status and being confined to bed most of the day. However, additional palliative measures, such as an attempt to reposition the G-tube, and placement of a Tenckhoff catheter for ascites, were performed. Proactive and frequent use of pain medications as well as antiemetics for further alleviation of symptoms was instituted. There were hopes to fix or palliate many problems, but unfortunately, many of them could not be fixed.

Dr. Abou-Alfa: Please allow me to introduce Ms. Cammarata, the social worker involved in this case. Ms. Cammarata, what can make a patient post on their door something like this?

Ms. Cammarata: This was a very complicated case of a woman newly diagnosed with advanced cancer who came to the hospital with high hopes for a cure. Unfortunately, she was told relatively quickly that there were limited treatment options, let alone a cure. She was a young mother and very frightened. I imagine being told within a short time that not only are you diagnosed with advanced cancer, but there is no treatment was incredibly difficult for her to understand and accept.

Dr O’Reilly: Were there any specifics in this case that made it more challenging?

Ms. Cammarata: She was a young single mother, with two relatively young daughters. The patient had a lot to live for—her kids meant everything to her and mom meant everything to her kids.

Dr Mukherji: Were there other signs of the patient dissatisfaction?

Dr. Viny: During our discussions, she often repeated “this is not me”, which was a statement that demonstrated the depersonalizing nature of her situation. She also said, “In the emergency room, we ‘treat and street’”, reflecting on her professional background as an emergency room nurse. Unfortunately this was not possible considering her medical situation.

Dr. Abou-Alfa: Dr. O’Reilly, if you saw this note on the door of one of your patients, what would you do?

Dr. O’Reilly: This is a very intimidating and challenging situation. The patient’s angst and distress with the team appears to be high. I don’t believe there is one “right way” to approach this. I would try to keep an open mind and have discussions with the family to get a sense of their understanding of the situation and come to a middle ground for the plan of care. These are labor-intensive and time-consuming discussions, but these difficult conversations are a common part of what we encounter every day as oncologists.

Dr. Abou-Alfa: Ms. Cammarata, a patient is putting written material in public space on the outside of her room door in the hallway on the medical ward. What should be done with the note on the door?

Ms. Cammarata: We needed to first establish an understanding of where the family was coming from and the meaning behind the note, before asking them to take it down. The patient and her family already had a difficult time trusting us. I feel if we told the patient and her family to take the note down from the door, then this would have caused increased mistrust. It can be very difficult to help support a family who does not trust the medical team.

Dr. Shamseddine: I concur. This is indeed a very difficult situation. Similarly, in the Middle East, families often expect cancer treatment for patients with poor performance status. We as healthcare workers, feel we want to be as proactive as possible for young patients and for patients with young children. However, based on our clinical knowledge and experience, we know this may very well not be the best thing for these types of patients. From my experience with talking to these types of patients, one of the things they don’t want to have taken away is hope. Therefore, I think a multidisciplinary approach is needed to manage these patients.

Dr. Osman: I concur with Dr. O’Reilly and Dr. Shamseddine. I think it is difficult to make this decision, and the possibility of trying chemotherapy that might deteriorate her situation further is a risk. For a patient with a sign like this on her door, it is important to engage by communication; hearing them first and discussing the limitations of the chemotherapy weighing out the risks and benefits, and helping them better understand the options, to make as rational and appropriate of a decision as possible.

Dr. Al-Olayan: This is a similar approach for us in Saudi Arabia. I concur that it is best to listen to the patient, describe and prescribe full supportive measures, and let the patient tell you their fears, and then help guide them. If the patient understands their disease, they will more likely understand why any cancer therapy options may be limited in that situation.

Dr. Li: Studies on the role of palliative chemotherapy in ECOG three patients with advanced solid tumors are limited. Sánchez-Muñoz et al. performed a retrospective analysis of 92 patients hospitalized with advanced solid tumors, ECOG 3-4, who were treated with palliative chemotherapy (2). Forty-nine percent of patients died within 30 days of chemotherapy. The authors concluded that palliative chemotherapy used for this group of patients likely provided no benefit for survival and may actually be contributing to poor quality of care.

Dr. Epstein: Another difficult part of this case was the fact that the patient was a health care worker herself, and this may have contributed to her insistence for some form of chemotherapy. While literature on nurses choosing medical treatments for themselves are limited, Ubel et al. demonstrated that when given hypothetical treatment choices for colon cancer, physicians were more likely to choose the treatment with a higher death rate for themselves compared to what they would recommend to a hypothetical patient (3). This suggests that cognitively, clinicians are more likely to not adequately weigh downsides to treatments as much for themselves, as when conceptualizing and communicating options to their patients.

Dr. Viny: Also difficult in this case was addressing the children of the cancer patient, and their needs. The US National Cancer Institute reports that approximately 24% of the cancer patient population is parenting children less than 18 years of age (4). Semple et al. performed a literature review which showed that in this cancer patient demographic, the three recurring concerns were of continuing to be a good parent, how to tell the children, and fear of losing normalcy at home (5).

Dr. Abou-Alfa: Ms. Cammarata, how should cancer parents approach their children?

Ms. Cammarata: There are a few important things that parents might want to consider before talking to their children about their cancer diagnosis and this includes, their relationship with their child, what if anything the child has been told about the parent’s diagnosis, as well as the age and cognitive level of the child. It is important to remember that the best way for parents to protect their child is by telling them the truth. Children need and depend on their parents so much that they can easily pick up on something that is wrong. Left to their own devices, children believe that something terrible has happened and they caused it. The more information children are told about their parent’s diagnosis the more they can visualize and understand. This can decrease fear and can ultimately lead to better coping with cancer as a family. Grenklo et al. found that children’s trust in the care of their dying parent was highest when receiving information about end-of-life issues before the death (6). The study found that distrust in the care provided was associated with an increased risk of depressive symptoms and was more prevalent in those children who did not receive medical information before the parent’s loss.

Dr. Viny: We ended up having a doubly frank but empathic discussion of risks/benefits and expectations of palliative chemotherapy with the patient and her family. The patient wanted chemotherapy even knowing the potential side effects. She was therefore treated with the modified de Gramont 5-FU regimen, without clinical improvement. She experienced grade 1 mucositis in the several days following this treatment. There were several additional discussions with the patient and her family about care goals and prognosis. In the end, the patient and family expressed a desire for natural death [a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order was therefore entered] and to move back closer to home for further cancer care. The patient was discharged from MSKCC to a local hospital in Pennsylvania 5 weeks after admission. She was then discharged to an inpatient hospice facility 1 week thereafter. She did not receive any more cancer treatment, and died 4 weeks later. A memorial was held in her honor and the patient’s two daughters later traveled to Europe per the patient’s previously stated wishes that they all “travel together” at some point, and her ashes were scattered in the places they visited.

Dr. Abou-Alfa: Dr. Epstein, how did you breakthrough in making some agreements with the patient? How should physicians communicate in these types of difficult cases? And do you consider that you “gave in” on the chemotherapy treatment decision against your medical opinion?

Dr. Epstein: I was indeed conflicted about ultimately prescribing chemotherapy to this patient. I ultimately believed it was the best thing to do for the following reasons: it was an untreated cancer, she was medically stable during her admission, her pain and other symptoms were well-palliated, her debility was completely cancer-related (thus if there was one treatment that had any chance of improving her debility, it was a chemotherapy trial), I discussed it with several medical oncologist colleagues, we gave single agent instead of combination chemotherapy, and ultimately, we had built a relationship of trust with the patient and family. This was achieved through a process of continued presence and visiting the patient throughout the hospital course every few days, and ongoing discussions about the medical aspects of the case. We were able to revisit their goals, values and perspectives, and to respond to emotion and the difficult nature of the situation, while always keeping on top of the medical issues. Trying to combine the medical and psychosocial presence with all providers was helpful, and built trust between them and us. We took a situation with danger of schism, as symbolized by the sign on the door, and transformed it to a place of togetherness, which was difficult to achieve, but we ultimately arrived at the best possible of all places. There are different communication skills (7,8) and palliative care training programs that teach this amalgamation of biologic and psychosocial treatments.

Certainly there are also different cultural underpinnings that must be taken into account when communicating with patients and their families. Our colleagues in Saudi Arabia illustrated this in a recent study of 203 patient and family member dyads which demonstrated that opposed to family member’s desires for the patient, most patients would prefer to be informed about bad news throughout the course of the illness (9). In the US, research into patient-physician communication during cancer care has also recently been conducted, and continues. For instance, The Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study demonstrated that the majority of stage IV lung and colon cancer patients are unclear about the incurability of their cancer (10), calling for examination into what is communicated to cancer patients, and how best to do so. Coping with Cancer was another US multisite, prospective cohort study of advanced cancer patients and yielded many findings, including that end of life discussions are associated with less aggressive care and earlier palliative care and hospice referrals (11); that aggressive care in the end of life setting results in worse patient quality of life and more difficult family bereavement (12); and that an alliance with the medical team is one factor deemed important by cancer patients at the end of life (13).

Dr Kanazi: In the US and beyond, palliative medicine is a rapidly growing medical subspecialty designed as an additional layer of support for patients, families, and the clinicians overseeing the care of people with serious illnesses. There is both generalist palliative care that all clinicians can give, such as pain medications and assessing patient concerns, and there is specialist palliative care, such as assisting with complex goals of care or the treatment of severe symptoms (14). The field is also hard at work in better determining which patients are most likely to benefit from the addition of palliative medicine services, both in the inpatient (15) and outpatient (16) setting.

Dr Epstein: Ultimately, relationship building and empathically seeking out where the patient was coming from, while helping them to understand the medical situation, proved useful in this case.

Acknowledgements

This case was presented at the MSKCC/American University of Beirut/National Guard Hospital gastrointestinal cancer conference on August 14, 2013 and was supported by the endowment gift of Mrs. Mamdouha El-Sayed Bobst and the Bobst Foundation.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 1982;5:649-55. [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Muñoz A, Pérez-Ruiz E, Sáez MI, et al. Limited impact of palliative chemotherapy on survival in advanced solid tumours in patients with poor performance status. Clin Transl Oncol 2011;13:426-9. [PubMed]

- Ubel PA, Angott AM, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Physicians recommend different treatments for patients than they would choose for themselves. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:630-4. [PubMed]

- Rauch PK, Muriel AC, Cassem NH. Parents with cancer: who’s looking after the children? J Clin Oncol 2002;20:4399-402. [PubMed]

- Semple CJ, McCance T. Parents’ experience of cancer who have young children: a literature review. Cancer Nurs 2010;33:110-8. [PubMed]

- Grenklo TB, Kreicbergs UC, Valdimarsdóttir UA, et al. Communication and trust in the care provided to a dying parent: a nationwide study of cancer-bereaved youths. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2886-94. [PubMed]

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist 2000;5:302-11. [PubMed]

- Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5748-52. [PubMed]

- Zekri JM, Karim SM, Bassi S, et al. Breaking bad news: Comparison of perspectives of Middle Eastern cancer patients and their relatives. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:abstr 9568.

- Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1616-25. [PubMed]

- Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4387-95. [PubMed]

- Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665-73. [PubMed]

- Zhang B, Nilsson ME, Prigerson HG. Factors important to patients' quality of life at the end of life. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1133-42. [PubMed]

- Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173-5. [PubMed]

- Glare P, Plakovic K, Schloms A, et al. Study using the NCCN guidelines for palliative care to screen patients for palliative care needs and referral to palliative care specialists. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2013;11:1087-96. [PubMed]

- Glare PA, Semple D, Stabler SM, et al. Palliative care in the outpatient oncology setting: evaluation of a practical set of referral criteria. J Oncol Pract 2011;7:366-70. [PubMed]