Intraperitoneal gemcitabine chemotherapy is safe for patients with resected pancreatic cancer: final clinical and pharmacologic data from a phase II protocol and recommended future directions

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States of America with an estimate of 34,000 deaths per year (1). Surgery represents the only definitive curative treatment option and R0 resection is associated with small improvements in disease-free and overall survival. Advances in surgical technique, anesthesia and perioperative care in the last two decades have led to a substantial decrease in perioperative mortality and morbidity especially in large volume centers (2). Unfortunately, a majority of patients present with advanced disease so that only 10–20% of patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer are able to undergo potentially curative surgery (3). Despite careful work-up for metastatic disease prior to surgery, long-term 5- or 10-year survival is rare, even after potentially curative R0 resection; the 5-year survival is between 10–25% (4). After curative resection, disease recurrence has been documented in the local and regional area (50%), on peritoneal surfaces (40–60%) and within the liver as hepatic metastases (50–60%) (5).

The pathophysiology of surgical treatment failure following the Whipple procedure is well established. As a consequence of the narrow margins of resection, there are a large number of local and regional failures. Tumor dissemination and implantation occurs within the resection site during surgery. Conceptually, this forms the basis for administration of perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. The major advantage of intraperitoneal chemotherapy is the high drug level that can be achieved locally with low systemic exposure (6). If used in the operating room this local-regional chemotherapy exposure occurs before pancreas cancer cells become fixed within scar tissue. Several randomized control trials have established the chemotherapy response of adjuvant systemic gemcitabine after potentially curative resection (7). However, success of systemic chemotherapy in controlling local disease has a weaker rationale and has never been confirmed in randomized trials. The pharmacokinetics of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) with gemcitabine administered intraoperatively establishes it as an excellent choice for local-regional use (8). This manuscript reports the phase I/II data on patients treated in a pilot protocol of HIPEC (12 patients) followed by long-term normothermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (NIPEC) (8 patients) gemcitabine. Patients had a complete resection of a pancreatic adenocarcinoma prior to intraperitoneal chemotherapy treatments. Clinical, pharmacologic, regional treatment failure, morbidity/mortality and survival data are reported. We present the following data in accordance with the MDAR reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-2020-02).

Materials and methods

Patients with a presumptive diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas were taken to the operating room for a standard pancreaticoduodenal resection. Following resection, HIPEC with gemcitabine at 1,000 mg/m2 was manually distributed within the peritoneal space for 60 minutes. The chemotherapy was in 1.5 liters/m2 of 1.5% dextrose peritoneal dialysis solution (9). Following HIPEC, the intestinal reconstruction was performed. Following these anastomoses, a permanent intraperitoneal port was placed (10). Then the abdomen was closed in a routine fashion.

At approximately 6 weeks postoperatively intraperitoneal gemcitabine in 1 liter of 1.5% dextrose peritoneal dialysis solution was infused through the intraperitoneal port. Treatments were on days 1, 8, and 15 with a gemcitabine dose of 1,000 mg/m2.

Patients were followed on a 3-monthly basis with CT scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis and CEA and CA 19-9 tumor markers at the same intervals. Special emphasis in follow-up was to diagnose the first site of pancreas cancer recurrence.

This clinical study and the pharmacologic data acquired was approved by the MedStar Georgetown Institutional Review Board, Protocol 2009-455.

Results

Data regarding hyperthermic intraperitoneal gemcitabine after Whipple procedure

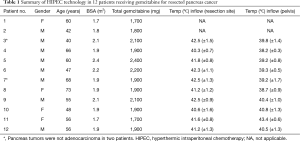

Pharmacologic data on 12 patients who had a pancreaticoduodenectomy plus intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal gemcitabine is available. The clinical features on 12 patients treated in Washington, DC are shown in Table 1. There were eight males. The median age was 56 with a range of 40–73. On final pathological review two tumors did not qualify as high-grade adenocarcinoma. Both of these patients remain alive and well. The gemcitabine dose was always 1,000 mg/m2. The median inflow temperature was 41.8 (±0.8) with a range of 40.3 (±0.7) to 42.5 (±1.5). The median outflow temperature was 39.2 (±0.8) with a range of 43.4 (±0.6) to 38.2 (±0.3).

Full table

Morbidity and mortality of hyperthermic intraperitoneal gemcitabine after Whipple procedure

Minor morbidity occurred in 4 of the 12 patients treated with HIPEC gemcitabine after pancreaticoduodenectomy. There was a single grade 2 neurologic event and a single grade 2 neutropenia. There was a single grade 2 urinary tract infection, and a single grade 2 cardiac arrhythmia. A single patient grade 3 event was a pancreatic fistula drained by interventional radiology without further incident. No patients were required to return to the operating room. The mean length of stay following the surgery was 14 (range, 9–21) days.

Pharmacokinetics of HIPEC gemcitabine

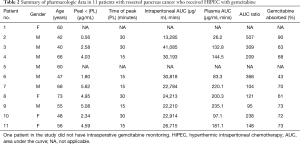

The pharmacologic data from the HIPEC procedure is available on 11 of 12 patients (Table 2). The peak plasma level varied from 5.62 to 0.56 µg/mL with a median of 4.03. Five of the 10 patients in whom peak plasma levels were available were above or close to the plasma level suggested by Gandhi to be associated with peak intracellular gemcitabine triphosphate (11). The time for peak plasma levels was 15 minutes in 5 patients, 30 minutes in 4 patients, and unavailable in 2 patients. The area under the curve (AUC) ratio was between 95 and 507 with a median of 209. The amount of gemcitabine absorbed during the 60 minutes of HIPEC was between 43% and 90% with a median of 70%.

Full table

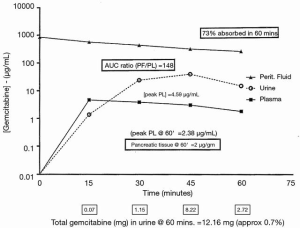

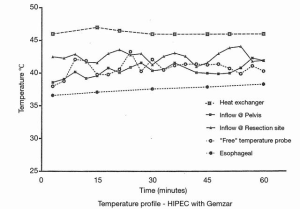

The complete pharmacokinetic information on a representative patient is shown in Figure 1. In this patient, 1,700 mg of gemcitabine in 2,550 mL of 1.5% dextrose was instilled into the open peritoneal space after the pancreaticoduodenal resection was complete. Temperature in the abdomen and pelvis was maintained at 42–43 °C (Figure 2). Uniform distribution of the heat and intraperitoneal chemotherapy solution was maintained by manual distribution (9) (Figure 3). The entrance of gemcitabine into tissues was confirmed in that 73% of the total dose of drug was cleared from the chemotherapy solution in 60 minutes. The peak plasma level occurred at 15 minutes and was 4.59 µg/mL. The AUC ratio of peritoneal fluid to plasma was 148. At the end of the hyperthermic gemcitabine lavage, a sample of blood from the portal vein showed a concentration approximately the same as plasma concentration at the same time. A biopsy of pancreatic tissue from the cut edge of the pancreas showed gemcitabine concentration of 2 µg/mL. Minimal drug was excreted in the urine.

NIPEC with gemcitabine for six cycles

There were eight patients eligible for NIPEC gemcitabine given through a permanently implanted intraperitoneal port. Seven of 8 patients completed the protocol. A single patient required a laparoscopic removal of the intraperitoneal catheter from within scar tissue that then allowed the prescribed treatments to be completed. One patient received only three cycles of NIPEC gemcitabine because she declined further treatments.

Survival

The median and mean survival was 29 months in the eight patients with adenocarcinoma who were treated with HIPEC plus long-term NIPEC gemcitabine. One patient is free of disease at 68 months (Table 3).

Full table

Discussion

Results from a second HIPEC gemcitabine protocol for resected pancreas cancer

Tentes and coworkers used HIPEC gemcitabine with resected pancreas cancer but did not use NIPEC gemcitabine (12). The 5-year survival rate was 23% and the median survival 11 months. The median disease-free survival time was 5 months. During follow-up 9 patients (50%) were recorded with recurrence. Three of them were stage II and six were stage III. All of these patients had liver metastases and no local-regional recurrence was recorded. Tentes and coworkers conclude that their data suggested that further studies to test HIPEC gemcitabine in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer are justified. Although the number of patients is small and the median follow-up time short, no patient developed local-regional recurrence. This suggests that HIPEC is likely to be effective in eradicating microscopic residual cancer deposits at the resection site and on peritoneal surfaces. Similarly, in a systematic review with perioperative hyperthermic or normothermic chemotherapy in patients with resected gastric cancer, favorable results of treatment were reported (13).

Safety of hyperthermic intraperitoneal gemcitabine chemotherapy following a Whipple procedure

The new treatment most heavily scrutinized as this protocol was initiated concerned the safety of HIPEC gemcitabine added to pancreaticoduodenectomy. This procedure carries a 22% incidence of high-grade complications and a 90-day mortality of 3.7%. Anastomotic fistula/leak/abscess is 14% (2). In our small series of patients, HIPEC gemcitabine when added to pancreaticoduodenectomy did not increase operative morbidity or mortality. A single patient did require percutaneous drainage of a collection at the pancreatico-jejunal anastomosis. The patient recovered from this uneventfully. Our conclusion along with Tentes et al. was that HIPEC gemcitabine could safely be added to the Whipple procedure in primary pancreas adenocarcinoma (12).

NIPEC long-term was well tolerated

The NIPEC gemcitabine given over 6 months was well tolerated. A single patient required a catheter extraction from a fibrous tunnel. All but one patient completed the six cycles of NIPEC gemcitabine. One patient was lost to follow-up after three cycles of NIPEC gemcitabine. The high incidence of intraperitoneal port complications reported following ovarian cancer cytoreduction by Walker et al. was not observed in this protocol (14). The lack of peritonectomy procedures and multiple visceral resections required for surgery in ovarian malignancy was not required for pancreas cancer patients. This plus catheter placement at the time of pancreaticoduodenectomy and HIPEC gemcitabine are likely to be responsible for this lack of port-related adverse events (10). These data show that the intraperitoneal route of gemcitabine administration was no more toxic than the systemic administration at the same doses.

Safe and effective intraoperative placement of an intraperitoneal port

In this protocol an intraoperative placement of an intraperitoneal port occurred in all eight patients (10). Following pancreatoduodenectomy, then HIPEC gemcitabine, then reconstruction, the intraperitoneal access device was placed. In all eight patients the placement was successful. No infections, bowel perforations, or inaccessibility of the port occurred. We concluded that placement of a subcutaneous port connected to an intraperitoneal catheter implanted just prior to abdominal closure and following a major cancer resection with HIPEC is safe and effective. The intraperitoneal port currently in use is the Bard Peritoneal Titanium Port with Attachable Peritoneal Catheter (Becton Dickinson, Covington, GA, USA).

Improvement in local control suggested by these data

The survival of our eight patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma was not inferior to other published data. However, the improvement in local control is worth noting. Local recurrence at the pancreas cancer resection site is reported to be 50% (5). This high rate of local failure persists even though neoadjuvant chemoradiation treatments have been used. Careful follow-up of our patients showed an absence of disease progression at the pancreas cancer resection site or on the surrounding upper abdominal peritoneal surfaces.

Absence of benefit of chemoradiation therapy for resected pancreas cancer shows a need for new innovative treatments

Knowledge that a small chance that surgical resection alone will be curative has led to multiple efforts to use adjuvant therapies, either prior to or at the time of pancreas cancer resection. In 1985, the Gastrointestinal Study Group (GITSG) reported on a randomized trial following an R0 pancreas cancer resection. The experimental arm of this trial was 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) plus radiation therapy performed following the resection. The control arm underwent resection only (15). The mean survival of the experimental group was 20 months as compared to surgery alone arm which was 11 months. Also, the 5-year survival was 18% with chemoradiation therapy and 8% with surgery alone. The recruitment into this trial was slow and it took 11 years to recruit 43 patients. It was closed prematurely due to this slow accrual but more importantly, a significant benefit favoring adjuvant chemoradiation therapy.

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) trial attempted to repeat the GITSG study and validate it with an adequately powered study (16). The adjuvant treatments using chemoradiation therapy were similar in the EORTC and GITSG studies. A difference was an absence of maintenance chemotherapy in the EORTC trial. In the EORTC trial, 218 patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma or ampullary adenocarcinoma were entered. The randomization was to pancreas resection with a split-course of radiotherapy (40 Gy) and concurrent 5-FU as a continuous infusion versus a surgery only cohort. The study was conducted for 11.7 years and the EORTC reported no difference in overall survival between the two groups of patients. Some have found a limitation of this study as a lack of maintenance chemotherapy.

The European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer (ESPAC) conducted a trial starting in 1994 and continuing for 6 years. This was the ESPAC-1 trial (17). They randomized 145 patients to a chemoradiation therapy arm and 144 had surgery only. The radiation was administered as a split course with a total of 50 Gy. The radiation therapy was given concurrent with 5-FU. There was no difference in the median survival. The chemoradiation therapy arm had a 15.5-month median survival and the no adjuvant treatment arm of the trial had a 16.1-month median survival. With final results reported, the median survival was 15.9 months if patients received adjuvant chemoradiation therapy, but this increased to 17.9 months in the group that did not receive chemoradiation therapy. This was significant with a P value of 0.05 suggesting a poorer result with the adjuvant chemoradiation therapy. In this final result, the estimated 5-year survival was 10% in patients who had pancreas resection plus chemoradiation therapy as compared to 20% in those who had surgery alone (P=0.05).

Gemcitabine is a good candidate for further studies of chemotherapy for resected pancreatic cancer

In contrast to inconsistent data for benefit from adjuvant chemoradiation therapy, the trials investigating adjuvant gemcitabine consistently showed benefit to pancreas cancer patients. In the CONKO-001 (Charité Onkologie) study, a multicenter randomized trial was conducted between July 1998 and December 2004 (18). This protocol was to test adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine administered after potentially curative resection of pancreas cancer as compared to resection alone. A total of 368 patients with gross complete (R0 or R1) resection of pancreas adenocarcinoma and no prior radiation or chemotherapy were randomized into two groups. The experimental group received adjuvant chemotherapy with six cycles of gemcitabine given on days 1, 8, and 15 every 4 weeks (n=179). In the control group, there was pancreas cancer resection alone (n=175). In the gemcitabine group, the median disease-free survival was 13.4 months as compared to 6.9 months in the surgery alone group. The disease-free survival at 3 and 5 years was 23.5% and 16.5% in the gemcitabine treated group, and 7.5% and 5.5% in the surgery only group, respectively. These authors concluded that 6 months of adjuvant gemcitabine after complete resection of pancreas cancer significantly increased median and disease-free survival.

In 2013, the benefits of adjuvant gemcitabine were confirmed (7). The effect of gemcitabine on disease-free survival was significant both in patients with an R0 or R1 resection. In this long-term follow-up analysis, adjuvant gemcitabine did improve the overall survival with resection plus gemcitabine resulting in a 22.8-month survival as compared to 20.2 months in the control group. The most impressive statistic was the delayed development of recurrent disease after complete resection plus adjuvant gemcitabine as compared to resection alone. This clinical trial strongly supported a benefit from adjuvant systemic chemotherapy with gemcitabine in resectable pancreas adenocarcinoma.

Current concepts of pancreas cancer management with multi-agent chemotherapy after cancer resection

Given the conflicting data concerning the use of chemotherapy and radiotherapy in resected pancreatic cancer, the optimal treatment of patients in this setting remains controversial. In Europe, chemotherapy with gemcitabine alone is generally accepted as standard of care; whereas in the United States, chemoradiation therapy may still be recommended especially with a R1 resection.

Recent success with multi-agent chemotherapy regimens used to treat patients with unresectable pancreas cancer has shown increased survival when compared to single-agent Gemzar. The use of a FOLFIRINOX regimen resulted in a median overall survival of 11.1 months as compared to 6.8 months in the gemcitabine group (19). Also, the addition of nab-paclitaxel to gemcitabine increased survival from 6.7 to 8.5 months (20). Clearly these multi-agent chemotherapy regimens are candidates for adjuvant treatment of resected pancreas cancer.

In the next clinical trial of intraperitoneal gemcitabine other chemotherapy agents would be used

There is data to recommend a doublet chemotherapy using gemcitabine with cisplatin or oxaliplatin. Heinemann et al. randomized 195 patients to receive either gemcitabine alone or gemcitabine plus cisplatin in patients with advanced pancreas cancer (21). The trial showed efficacy and safety of an every 2-week treatment with gemcitabine combined with cisplatin. The median overall survival and progression-free survival were improved in the doublet as compared to gemcitabine alone, although the difference did not reach statistical significance. The French Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Group (GERCOR) with the Italian Group for the Study of Gastrointestinal Tract Cancer (GISCAD) intergroup study compared gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin to gemcitabine alone (22). The pooled analysis of the GERCOR/GISCAD intergroup study indicated that the combination of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin significantly improved progression-free survival and overall survival as compared to gemcitabine only in patients with advanced pancreas cancer who showed a good performance status. The combination of gemcitabine by intraperitoneal port plus systemic cisplatin or oxaliplatin would be a logical next step for protocols with long-term normothermic bidirectional chemotherapy.

A multi-agent chemotherapy regimen used to treat patients with unresectable disease has shown increased survival when compared to single-agent Gemzar. In 342 randomized patients, the FOLFIRINOX regimen resulted in a median overall survival of 11.1 months as compared to 6.8 months in the gemcitabine group. Clearly, this multi-agent chemotherapy regimen becomes a candidate for adjuvant treatment of resected pancreas cancer (19). The possibility to combine intraperitoneal gemcitabine with agents from the FOLFIRINOX regimen is a promising research plan.

In a more recently, Von Hoff and colleagues performed a phase III multicenter international trial which compared nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine with gemcitabine alone. This was front-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer. The overall survival was superior in patients receiving nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine (8.5 vs. 6.7 months; HR: 0.72; P=0.000015). Also, the 1- and 2-year survival rates were superior in the combination treatment (35% vs. 22%, P=0.0002; 9% vs. 4%, P=0.021). Currently, nab-paclitaxel is approved for treatment of pancreas cancer (20).

Also, nab-paclitaxel has been added to gemcitabine and shown to improve outcome with resected pancreas cancer. Tempero and colleagues in the APACT phase III randomized trial showed that adjuvant treatment with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine was superior to gemcitabine alone (23). Also, Ielpo and colleagues compared gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel as a neoadjuvant treatment prior to pancreaticoduodenectomy to surgery alone. In the borderline resectable group, survival was four times higher compared to surgery alone (43.6 vs. 13.5 months, P=0.001). From these data systemic or intraperitoneal nab-paclitaxel can be considered as a second chemotherapy agent to be added to intraperitoneal gemcitabine (24).

In summary, this manuscript develops a hypothesis suggesting potential benefit for the use of HIPEC and NIPEC with gemcitabine in the management of resected pancreas cancer. The data taken together provide a rationale for improved local control in patients with resected pancreas cancer. The preliminary analysis of early data from our study shows acceptable morbidity and no mortality following intraperitoneal gemcitabine administration. The pharmacologic analysis confirms a high peritoneal to plasma AUC ratio for gemcitabine exposing the surfaces at risk for recurrence to high levels of gemcitabine.

Future plans

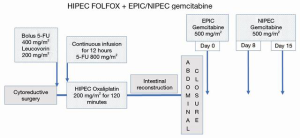

Possible addition of other intravenous or intraperitoneal drugs is contemplated to construct a bidirectional (combined intraperitoneal and intravenous) treatment plan. Our strong recommendation is to combine intraperitoneal gemcitabine with a platinum chemotherapy. Oxaliplatin because of its reduced renal toxicity would be recommended. The perioperative protocol is illustrated in Figure 4. It begins with HIPEC as a perioperative FOLFOX (25). The drug added which is specific for pancreas cancer is gemcitabine. It is given at a reduced dose (500 mg/m2) as EPIC in the operating room. Then on day 8 and 15 additional doses of NIPEC gemcitabine are administered. The combined FOLFOX plus intraperitoneal gemcitabine is continued at 3–4 weeks intervals for an additional five cycles. Doses of intraperitoneal gemcitabine are escalated as tolerated from 500 to 1,000 mg/m2 on day 0, 8 and 15 after the standard FOLFOX regimen. A pilot phase I/II protocol is planned.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology, for the focused issue “Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Peritoneal Metastases: HIPEC, EPIC, NIPEC, PIPAC and More”. This article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the MDAR reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-2020-02

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-2020-02). The focused issue was sponsored by the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI). PHS served as the unpaid Guest Editor of the focused issue. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 2013;63:11-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pugalenthi A, Protic M, Gonen M, et al. Postoperative complications and overall survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol 2016;113:188-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schneider G, Siveke JT, Eckel F, et al. Pancreatic cancer: basic and clinical aspects. Gastroenterology 2005;128:1606-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sener SF, Fremgen A, Menck HR, et al. Pancreatic cancer: a report of treatment and survival trends for 100,313 patients diagnosed from 1985-1995, using the National Cancer Database. J Am Coll Surg 1999;189:1-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Warshaw AL, Fernández-del Castillo C. Pancreatic carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1992;326:455-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dedrick RL. Theoretical and experimental bases of intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Semin Oncol 1985;12:1-6. [PubMed]

- Oettle H, Neuhaus P, Hochhaus A, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. JAMA 2013;310:1473-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pestieau SR, Stuart OA, Chang D, et al. Pharmacokinetics of intraperitoneal gemcitabine in a rat model. Tumori 1998;84:706-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugarbaker PH, Averbach AM, Jacquet P, et al. A simplified approach to hyperthermic intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIIC) using a self retaining retractor. Cancer Treat Res 1996;82:415-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugarbaker PH, Bijelic L. Adjuvant bidirectional chemotherapy using an intraperitoneal port. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2012;2012:752643 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gandhi V. Questions about gemcitabine dose rate: answered or unanswered? J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5691-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tentes AA, Kyziridis D, Kakolyris S, et al. Preliminary results of hyperthermic intraperitoneal intraoperative chemotherapy as an adjuvant in resectable pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2012;2012:506571 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yan TD, Black D, Sugarbaker PH, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials on adjuvant intraperitoneal chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:2702-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walker JL, Armstrong DK, Huang HQ, et al. Intraperitoneal catheter outcomes in a phase III trial of intravenous versus intraperitoneal chemotherapy in optimal stage III ovarian and primary peritoneal cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol 2006;100:27-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalser MH, Ellenberg SS. Pancreatic cancer. Adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection. Arch Surg 1985;120:899-903. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J, Sahmoud T, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann Surg 1999;230:776-82; discussion 782-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, et al. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1200-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007;297:267-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1817-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1691-703. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3946-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Louvet C, Labianca R, Hammel P, et al. Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:3509-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tempero MA, Reni M, Riess H, et al. APACT: Phase 3, multicenter, international, open-label, randomized trial of adjuvant nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine vs gemcitabine for surgically resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:abstr 4000.

- Ielpo B, Caruso R, Duran H, et al. A comparative study of neoadjuvant treatment with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel versus surgery first for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Surg Oncol 2017;26:402-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugarbaker PH, Stuart OA. Rationale and pharmacologic data in favor of perioperative FOLFOX in management of peritoneal metastases of colorectal cancer. Report of 2 patients. Int J Surg Case Reports 2020; In press. [Crossref]