Approximately 150 cases of benign multicystic peritoneal

mesothelioma, with various presentations have been

reported since it was first described by Mennemeyer and

Smith in 1979 (

3-12). Upon extensive literature review, no

report of BMPM presenting with pneumoperitoneum and

pneumotosis intestinalis was identified. This disease is quite

rare (0.15/100,000 annually) which makes its diagnosis,

treatment, origin, and pathogenesis a unique clinical

challenge (

3).

Benign multicystic peritoneal mesothelioma lesions

usually occur in the peritoneum along the pelvic cul de

sac, uterus, and rectum, but may occasionally involve

the round ligament, small intestine, spleen, liver, kidney,

previous scars, or the appendix (

2,

1,

3,

4). Unlike malignant

mesothelioma, BMPM has not been shown to have an

association with asbestos exposure. In as many as half of

the cases, lesions have recurred within a few months to

years after resection (

1). Although it is considered benign,

rare cases have been reported to proceed to malignant

transformation (

5).

BMPM, also referred to as multilocular inclusion

cysts, occurs most frequently in young to middle-aged

premenopausal women (

1,

2). Rarely, it occurs in males

(

10,

14). The disease has been considered to be either a

hyperplastic reactive lesion or a benign neoplasm. Due to

its reported association with previous abdominal surgery

and endometriosis, some authors support the notion

of BMPM being a non-neoplastic reactive lesion (

2),

however, recurrence after partial resection and malignant

transformation resulting in death has been well documented

over the years (

5).

The lesions typically appear as single or multiple small,

thin-walled, translucent, unilocular cysts that may be

attached or free in the peritoneal cavity (

1). Extraperitoneal

locations such as the pleura , spermatic cord, and pericardium have been rarely reported (

2). Grossly the

cysts are most often seen attached and growing on the

surfaces of the pelvic cul de sac, uterus, and rectum in a

multilocular mass. The cystic fluid varies from yellow

to watery or gelatinous in consistency with the cytology

showing sheets of benign monomorphous mesothelial cells

(

2,

1). On microscopic examination BMPM cysts are lined

by a single layer of flattened to cuboidal mesothelial cells

which occasionally have a “hob-nail” appearance. In up to

one third of the cases, the lining of the cells can undergo

adenomatoid or squamous metaplasia (

1,

2).

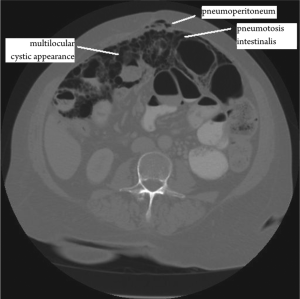

Although pneumoper itoneum and pneumatosi s

intestinalis have a wide variety of differential diagnoses

ranging from benign to life threatening, these conditions

have never been reported as associated with benign

multicystic mesothelioma. The differential diagnosis of

BMPM includes a variety of malignant and benign lesions

that present as cystic or multicystic abdominal masses.

Cystic lymphangioma, cystic adenomatoid tumors, cystic

mesonephric duct remnants, endometriosis, mullerian

cysts involving the retroperitoneum, and cystic forms

of endosalpingiosis are several of the benign lesions that

should be considered in the differential (

11). Multilocular

cystic lymphangiomas are the most commonly confused

lesions with BMPM. Unlike BMPM, cystic lymphangiomas

usually occur in male children in extrapelvic regions. They

are usually found localized to the small bowel, omentum,

mesocolon, or retroperitoneum and contain chylous

contents. Unlike BMPM, they also have mural lymphoid

aggregates and smooth muscle unlike (

1,

11). Malignant

lesions to consider are malignant mesothelioma and serous

tumors that involve the peritoneum.

BMPM usually presents with vague lower abdominal

pain, mass, or both, but is also commonly diagnosed

incidentally upon laparotomy for other surgeries (

1). The

patient may also present with obstructive symptoms such as

nausea, bloating, or vomiting. Despite its relatively benign

process some patients may present with an acute abdomen

(

11). CT scans may be diagnostically beneficial but, as in

this case, can also indicate a more acute need for surgery as

actually necessary. Pre-operative fine needle core biopsies

have been reported to be of some benefit in the differential

diagnosis of BMPM (

11,

16). Cytologic features of peritoneal

washings in cases of BMPM have shown the washings

to be hypercellular with a population of mesothelial and

squamous metaplastic cells (

6). Ultimately, the diagnosis is

usually made by the pathologist after surgical resection has

been performed.

Due to its rarity, BMPM treatment options remain an

area of controversy and there is no streamlined treatment

plan. Currently aggressive surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment with palliative debulking and reoperation for

recurrence (

15,

11,

5). With up to 50 percent recurrence rates

and its malignant potential, debulking surgery does not

appear to be the most acceptable treatment option for these

patients. Patients may suffer from poorly controlled chronic

abdominal and pelvic pain (

15). Uncertain results have been

reported with patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy

and/or radiation therapy (

5). Other approaches such

as sclerosive therapy with tetracycline, continuous

hyperthermic peritoneal perfusion with cisplatin, and

antiestrogenic drugs have been suggested (

11). The optimal

treatment may be cytoreductive surgery with peritonectomy

combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy

to eliminate all gross and microscopic disease (

5). The goal

of this treatment regimen is to reduce the likelihood of

progression or recurrence.

Although the prognosis for BMPM is ver y good,

aggressive approaches to this disease should be considered.

Patients have a high likelihood of recurrence and repeat

surgeries are common. The intention of this report is to

increase the awareness of this disease entity and to consider

it whenever the patient’s presentation does not match that

of the working diagnosis. This patient presented without

peritoneal signs despite a CT scan that suggested a more

severe pathology. Before jumping into an exploratory

laparotomy based on imaging findings, surgeons should

trust our physical exam and pursue a more definitive

diagnosis. With a definitive diagnosis we can approach

the surgical issue in the most appropriate manner. In this

case, a diagnosis could have been made by a minimally

invasive technique such as a needle biopsy or a diagnostic

laparoscopy. Once a definitive diagnosis of BMPM is made,

then a single surgery should be the goal to eliminate all

gross and microscopic disease.