Systematic review on quality of life outcomes after gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma

Introduction

Rationale

Gastric cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide (1). It is the second most common form of cancer in first world countries (2), with 930,000 new cases and 700,000 deaths reported yearly (3). Since the first successful operation in 1881 (4), partial or total gastrectomy remains the only curative intervention for localised gastric cancer (3,4). Post-operative survival has improved dramatically. The 5-year survival rate of all resections rose from 20.7% before 1970 to 28.4% by 1990, while 5-year survival rates of curative resections increased from 37.6% to 55.4% during the same period (5). Contemporary studies quote 5-year survival rates of 33-50% (6).

The best treatment for gastric cancer would offer the longest survival, the least toxicity, and the best health-related quality of life (HRQOL) (1). However, survival remains unsatisfactory due to late diagnosis which portends a worse prognosis (7). Treatment-related adverse effects are also difficult to reduce. Therefore, a key goal of surgery is to achieve good symptomatic control and HRQOL (8,9). HRQOL is considered one of the most important parameters in assessing the impact of oncological treatment on patients (10).

To date, there has been no systematic review on HRQOL after gastrectomy. This is critical in outcome evaluation and allows both patient and clinician to assess whether the procedure will be worthwhile.

The aim of this study was to evaluate HRQOL outcomes in patients after partial or total gastrectomy compared to pre-operative status and age-matched reference populations.

Methods

The structure of this systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines (11).

Definition and measurement of HRQOL

HRQOL encapsulates an individual’s physical, emotional and psychological health as well as social and functional status. This is important in determining the broad health-related implications of gastric cancer and post-operative HRQOL (12).

Commonly used HRQOL instruments were Gastroenterology Quality of Life Index (GQLI) (13), Gastrointestinal Symptoms Rating Scale (GSRS) (14), Life After Gastric Surgery (LAGS) (15), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Rating Scale (16), European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire—cancer specific (EORTC QLQ-C30) (17), European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire—colon specific (EORTC QLQ-STO22) (18), and Medical Outcomes 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) (19).

Detailed descriptions of all scoring systems and HRQOL instruments are outlined in the appendix Table 1.

Full table

Eligibility criteria

Studies considered for review had the following characteristics: (I) all patients over 18 years of age; (II) gastric carcinoma as the primary indication for surgery; (III) complete or partial gastrectomy as a primary procedure; and (IV) HRQOL data recorded. These studies were restricted according to the following report characteristics: (I) published after January 2000; (II) English language; and (III) original research only.

Information sources and search strategy

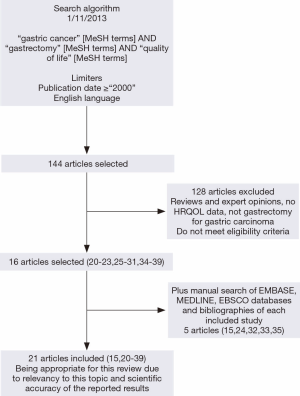

On November 2013, a literature search was conducted using MeSH keyword search on PubMed (MEDLINE) for all studies which matched the eligibility criteria above (Figure 1). An additional manual search of OVID (MEDLINE) and EBSCOhost (EMBASE) as well as bibliographies of each included study was conducted to identify studies not covered by the initial MeSH keyword search. All identified articles were retrieved from the aforementioned databases.

Study selection

Following the search, two reviewers independently performed screening of titles and abstracts after MeSH keyword and manual searches. Studies were excluded if they did not meet eligibility criteria. Consensus for studies included for review was achieved by discussion between reviewers based on the pre-determined eligibility criteria.

Data items and extraction

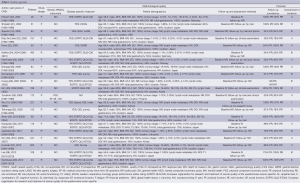

All data items for assessment of study quality (Table 1) and study results (Table 2) were pre-determined. Data extraction was then performed by two reviewers using standardised pilot forms.

Full table

Synthesis of results

Results were synthesised by a narrative analysis through the use of pre-determined items, as outlined above. HRQOL was categorised into a number of health domains, including global health, physical health, emotional health, functional health and social health. Subsequently, results of individual studies were amalgamated according to these health domains.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias in individual studies was assessed by a qualitative analysis based on study quality and data tabulated in Table 1. Overall level of evidence of each study was also assessed (40).

Results

Study selection

Twenty-one studies were included for review (Figure 1) (15,20-39). Heterogeneous data precluded meta-analysis. Key factors were statistical (no pre-operative data, data not expressed as mean ± standard deviation) and methodological (follow-up time point not reported, heterogeneous HRQOL scoring systems that could not be amalgamated) heterogeneity. Full details and results of the reviewed articles are provided in Tables 1,2.

Study characteristics and risk of bias

The strength of evidence was analysed systematically in this review (Table 1). We aimed to minimise reporting bias with a comprehensive search of the literature for all studies that meet our eligibility criteria. Most studies were conducted in Europe and Asia. The average age at surgery was 51-71 years. Males accounted for 36-93% of patients. The sample size ranged from 44 to 623. Nine studies had less than 100 patients (15,20,21,23,26,28,33,35,39).

Follow-up was conducted by mail, telephone and clinical examination over a period of 2 weeks to 8.9 years. According to previous guidelines, a response rate of >85% (loss to follow-up <15%) is considered ideal for treatment received analyses (41). This was not achieved in ten studies (15,22,24,27,28,30,32,34,35,37). Patients who failed to respond may be more likely to be unwilling or unable to due to illness or being deceased, which may skew HRQOL positively.

There were 13 prospective studies and 8 retrospective studies. This is an important source of bias in the reviewed studies. Retrospective collection of data may be inconsistent, with selection bias and lack of pre-operative data as key factors (42). The overall level of evidence of each study was analysed. A total of 13 studies had a level of evidence I or II (20-23,25,26,29-31,33,34,36,37) and 8 studies had a level of evidence III or IV (15,24,27,28,32,35,38,39).

Mortality and morbidity in included studies

Studies included for review reported early mortality, 1- and 5-year survival of 4% (20), 80-99% (20,27,29), and 15-20% (27) respectively.

Complications specific to gastrectomy were assessed in 10 studies (23,26,29-31,33-35,37,38). There was no statistically significant correlation between post-operative complications and HRQOL found in studies included for review (22,27,39,40).

HRQOL results

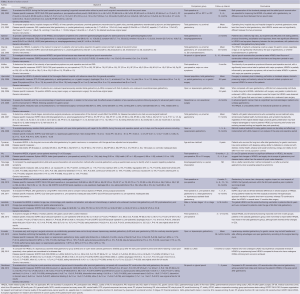

Complete results of qualitative analysis are provided in Table 2 with data at latest follow-up tabulated.

Overall health domains

Overall HRQOL and global health status at 1 year is equal to or better compared to pre-operatively (20,24,33,34,36). Global health status in the EORTC QLQ-C30 declines immediately post-operatively, but improvement occurs with recovery at 1-3 months, before reaching or surpassing pre-operative levels by 1 year (24,34,36). Faster recovery may occur with global health status reaching baseline levels by 3 or 6 months (24,33).

HRQOL varies between different surgical operations. When comparing total gastrectomy against partial gastrectomy, most studies reported no statistically significant differences between global health status scores (15,21,22,28). Two studies reported total gastrectomy patients scored lower in the global health status dimension of the EORTC QLQ-C30 at 1 year compared to partial gastrectomy, but these differences did not exceed 10 points and by 5 years there was no difference between the two groups (25,39). Data on the difference between laparoscopic and open surgery is conflicted. Lee et al. reported no statistical differences between the two groups (38), while Kim et al. noted significantly better outcomes in the laparoscopic group compared to the open surgery group (29). Patients in both these studies did not achieve their pre-operative HRQOL levels in the EORTC QLQ-C30.

Physical health domain

Physical health deteriorates rapidly after surgery, with patients reporting considerably lower scores in the EORTC QLQ-C30 after discharge (20,24,34). Recovery begins between 4 to 6 weeks and continues to around 3 months (33,34). However, physical health scores in the EORTC do not reach baseline levels. Other studies reported better outcomes, but also noted a longer recovery time, with scores equalling or surpassing pre-operative levels at 6 or 12 months (33,36).

The majority of studies report better physical health in patients undergoing partial gastrectomy compared to total gastrectomy (21,25,28,34,39). Two studies indicated total gastrectomy patients achieved better scores (15,22), but this was not statistically significant in one (15). There was no major difference between laparoscopic and open surgery patients’ physical functioning scores (29). Both groups experienced a decline after surgery which slowly improved with recovery, but remained below baseline levels at 90 days (29).

Emotional health domain

Post-operative emotional well-being levels on EORTC showed continuous improvement of scores from immediately after surgery to 3 months, before plateauing to 12 months (34,36). An initial decline in emotional health may occur, but eventually becomes similar or better than baseline levels (24,29). Avery et al. reported no change in scores before or after surgery (33).

Patients who underwent partial gastrectomy reported significantly better results compared to those who had undergone total gastrectomy (20,25,28,39). By 5 years HRQOL after partial or total gastrectomy may become similar (39). Two studies reported better scores in the total gastrectomy group, but this was not statistically significant (15,22). HRQOL results are conflicted in comparing laparoscopic and open surgery (29,38). Kim et al. reported a marked improvement in patients following laparoscopic surgery, while patients undergoing open surgery had an initial decline before rising to above baseline levels after 30 days (29).

Social health domain

Social wellbeing scores followed a similar trend of initial deterioration followed by recovery to a level equal to or greater than baseline (33,34,36). Two studies reported worse social functioning outcomes (20,24). Hoksch et al. noted that recovery was slower than other health domains, but patients were still able to complete housework and the majority returned to their jobs (20).

Total gastrectomy appears to confer superior HRQOL scores, but statistical significance is not achieved (15,22). Hjermstad et al. suggest partial gastrectomy confers greater benefits (25). Huang et al. report no differences in scores (28). Similar scores were reported at 1 year after surgery, but partial gastrectomy patients experienced a decline in social wellbeing while the scores of total gastrectomy patients remained unchanged after this point (39). Comparisons between laparoscopic and open surgery showed no difference (38).

Functional health domain

Functional health is a measure of a patient’s ability to function in life and society. Most patients reached a post-operative functional state at least as good as pre-operatively by 6 or 12 months in role functioning on EORTC (24,33,34). Scores were only slightly lower than baseline in two studies (20,36). Cognitive functioning was largely unaffected by surgery and remained near baseline levels throughout follow-up (20,24,33,34,36).

Partial gastrectomy patients reported higher functional health scores on the EORTC compared to total gastrectomy (25,28,39). Spector et al. reported total gastrectomy patients having a higher, but not statistically significant score (15). Kim et al. reported that patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery attained higher functional status compared to those undergoing open surgery, although both groups remained below pre-operative levels (29). Lee et al. suggested laparoscopic surgery resulted in significantly lower role functioning scores on the EORTC (38).

Patient satisfaction was similar between total and partial gastrectomy patients (21). However, patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery showed a markedly higher level of post-operative satisfaction compared to patients undergoing open surgery (26).

Factors affecting HRQOL

Patients with increased symptom frequency and severity, separate from their post-operative complications, were more likely to experience a lower HRQOL (15). Those older than 65 or 70 years of age experienced higher scores in all dimensions of HRQOL compared to younger patients (22,35). However, they were also more likely to experience more severe symptoms after surgery. Díaz De Liaño et al. reported that women were more likely to achieve higher scores on EORTC, but there were no significant differences (22).

Discussion

Summary of evidence and interpretation

This systematic review summarises modern outcomes after gastrectomy and this is reflected in the inclusion criteria where only studies published from the year 2000 onwards were included.

Despite improvements in peri-operative morbidity, mortality, and long-term survival, gastrectomy remains a major surgical intervention. The potential for harm and negative impact on HRQOL after surgery must be carefully balanced against the survival benefits and chance of cure. The monitoring of HRQOL after gastrectomy is advised as a standard of care and is critical as both an outcome measure and assessment of patients’ progress after surgery (28). Most patients experience a significant decline in overall health, physical and functional domains of HRQOL within the first few months after surgery which is then followed by significant improvements by 1 year. Patients should expect this initial decline in HRQOL in the early post-operative period as a trade-off for longer survival and improved HRQOL in the longer term. The greatest dilemma facing clinicians and patients is whether the prolonged survival is long enough for the patient to pass the initial recovery period and experience the positive HRQOL benefits.

This review shows that even though patients suffered from ongoing gastrointestinal symptoms up to 6 months after surgery, physical health improves after recovery. There is a noticeable decline within the first 3 months, but between 6 months and 1 year, physical health becomes at least as good as pre-operatively. However, it appears HRQOL is not well maintained after 5 years. Patients should be counselled about ongoing symptoms and the decline in physical health during the early post-operative period, as the severity of symptoms appears to be closely related to post-operative HRQOL. This will allow for realistic expectations of surgical outcome. These results indicate further emphasis on treatment of post-operative and disease-related symptoms is required.

Emotional health is the greatest beneficiary of surgery. Despite the relatively high morbidity of gastrectomy and the initial decline in physical health after surgery, emotional health improves. This may be the product of increased hope for prolonged survival, especially once physical recovery begins and the severity and frequency of symptoms decreases. In the context of an already limited life expectancy, emotional health benefits are critical for patients and this should be stressed during pre-operative decision making.

Surgery appears to have little impact on social health domains, with social functioning remaining unchanged up to 1 year post-operatively. By the time patients are being evaluated for gastrectomy, the effects of diagnosis and long-term impacts on social health parameters have likely plateaued. Unless the patients, and more importantly their friends and families, are aware of the curative intent of surgery and post-operative results, attitudes towards the patient and their diagnosis are unlikely to change.

Despite the initial deterioration, functional status is at least as good as pre-operatively in most patients by 1 year and only marginally below baseline for others. Functional status is a key marker of success after surgery as it allows patients independence and the capacity to undertake their normal daily activities. Even though functional status may not necessarily be superior to pre-operatively, similar results are a positive finding in the context of a morbid operation. The ability to work and resume normal daily activities is a crucial outcome of surgery, and impacts positively on HRQOL through a number of factors. In addition, the maintenance of cognitive function is a positive finding which is very important for patients and families in particular.

Data on HRQOL compared to reference populations is limited and unclear. Overall HRQOL appears to be comparable to that of the general population, with no statistically significant differences between the two groups in any of the health domains. These results are to be interpreted with caution because the comparison reference populations are heterogeneous and may not be appropriately matched populations for age, disease status and type of surgical operation.

The majority of studies reviewed had levels of evidence II or III, with only one randomised control trial included. There appeared to be no significant difference in results between studies of different levels of evidence, with most studies concluding similar results in all HRQOL domains.

When evaluating cancer treatment, post-operative HRQOL is widely accepted as an increasingly important outcome of surgical interventions, is on par with mortality and survival (36). The limited life-expectance of gastric carcinoma patients further increases the importance of HRQOL. HRQOL information allows patients and clinicians to make more informed pre-operative decisions, as well as improve patient care and symptom management.

To our knowledge this is the first systematic review on HRQOL outcomes following gastrectomy and provides a synthesised modern reference when considering patients for surgery.

Limitations

A key limitation of this study was that a meta-analysis was unable to be performed due to clinical, statistical and methodological heterogeneity. Furthermore, the HRQOL findings of this review may not be applicable to all patients. Patients with gastric carcinoma have a variety of tumour stages, lymph node involvement, extent of disease and prognosis which were not analysed separately. However, it appears the type of surgery remains the largest influence on post-operative HRQOL. The superior expertise and operative outcomes of high volume tertiary centres compared to institutions with lower volumes is also important. These factors may all have different impacts on HRQOL.

Language bias may be present due to the English language eligibility criteria, as none of the contributing authors could translate from other languages.

Implications for future research

This review demonstrates the lack of pre-operative compared to post-operative HRQOL results of the same patients as well as appropriate data for meta-analysis. Prospective studies with pre-determined follow-up time points that accurately reflect current survival rates and consistent use of previously validated HRQOL instruments are recommended. Multi-centre involvement is ideal to increase patient numbers and minimise bias. In addition, future studies should compare HRQOL results to properly matched sample populations, such as patients with gastric carcinoma who don’t receive gastrectomy. Further investigation is required on defining the predictors of better HRQOL outcomes and to define strategies for improvement.

Conclusions

Gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma has a demonstrable benefit for patients’ HRQOL in a broad range of health domains. Overall, HRQOL returns to similar or better levels by 1 to 2 years compared to before surgery. The most significant improvements were demonstrated in emotional health which is a particularly salient component of HRQOL in oncology patients.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Munene G, Francis W, Garland SN, et al. The quality of life trajectory of resected gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol 2012;105:337-41. [PubMed]

- Viudez-Berral A, Miranda-Murua C, Arias-de-la-Vega F, et al. Current management of gastric cancer. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2012;104:134-41. [PubMed]

- Ohtani H, Tamamori Y, Noguchi K, et al. Meta-analysis of laparoscopy-assisted and open distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Surg Res 2011;171:479-85. [PubMed]

- Lew JI, Posner MC. Surgical Treatment of Localized Gastric Cancer. In: Posner MC, Vokes EE, Weichselbaum RR, editors. American Cancer Society Atlas of Clinical Oncology, Cancer of the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract. Hamilton: BC Decker Inc., 2002;13:252-77.

- Akoh JA, Macintyre IM. Improving survival in gastric cancer: review of 5-year survival rates in English language publications from 1970. Br J Surg 1992;79:293-9. [PubMed]

- Dassen AE, Dikken JL, van de Velde CJ, et al. Changes in treatment patterns and their influence on long-term survival in patients with stages I-III gastric cancer in The Netherlands. Int J Cancer 2013;133:1859-66. [PubMed]

- Menges M, Hoehler T. Current strategies in systemic treatment of gastric cancer and cancer of the gastroesophageal junction. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2009;135:29-38. [PubMed]

- Cervantes A, Roselló S, Roda D, et al. The treatment of advanced gastric cancer: current strategies and future perspectives. Ann Oncol 2008;19 Suppl 5:v103-7. [PubMed]

- Cardoso R, Coburn NG, Seevaratnam R, et al. A systematic review of patient surveillance after curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a brief review. Gastric Cancer 2012;15 Suppl 1:S164-7. [PubMed]

- Dorcaratto D, Grande L, Ramón JM, et al. Quality of life of patients with cancer of the oesophagus and stomach. Cir Esp 2011;89:635-44. [PubMed]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:e1-34. [PubMed]

- Kaptein AA, Morita S, Sakamoto J. Quality of life in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:3189-96. [PubMed]

- Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, et al. Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg 1995;82:216-22. [PubMed]

- Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Dotevall G. GSRS--a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci 1988;33:129-34. [PubMed]

- Spector NM, Hicks FD, Pickleman J. Quality of life and symptoms after surgery for gastroesophageal cancer: a pilot study. Gastroenterol Nurs 2002;25:120-5. [PubMed]

- Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 1982;5:649-55. [PubMed]

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:365-76. [PubMed]

- Vickery CW, Blazeby JM, Conroy T, et al. Development of an EORTC disease-specific quality of life module for use in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer 2001;37:966-71. [PubMed]

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473-83. [PubMed]

- Hoksch B, Ablassmaier B, Zieren J, et al. Quality of life after gastrectomy: Longmire's reconstruction alone compared with additional pouch reconstruction. World J Surg 2002;26:335-41. [PubMed]

- Shiraishi N, Adachi Y, Kitano S, et al. Clinical outcome of proximal versus total gastrectomy for proximal gastric cancer. World J Surg 2002;26:1150-4. [PubMed]

- Díaz De Liaño A, Oteiza Martínez F, Ciga MA, et al. Impact of surgical procedure for gastric cancer on quality of life. Br J Surg 2003;90:91-4. [PubMed]

- Kono K, Iizuka H, Sekikawa T, et al. Improved quality of life with jejunal pouch reconstruction after total gastrectomy. Am J Surg 2003;185:150-4. [PubMed]

- Kahlke V, Bestmann B, Schmid A, et al. Palliation of metastatic gastric cancer: impact of preoperative symptoms and the type of operation on survival and quality of life. World J Surg 2004;28:369-75. [PubMed]

- Hjermstad MJ, Hollender A, Warloe T, et al. Quality of life after total or partial gastrectomy for primary gastric lymphoma. Acta Oncol 2006;45:202-9. [PubMed]

- Ikenaga N, Nishihara K, Iwashita T, et al. Long-term quality of life after laparoscopically assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Journal of laparoendoscopic & advanced surgical techniques Part A 2006;16:119-23. [PubMed]

- Samarasam I, Chandran BS, Sitaram V, et al. Palliative gastrectomy in advanced gastric cancer: is it worthwhile? ANZ J Surg 2006;76:60-3. [PubMed]

- Huang CC, Lien HH, Wang PC, et al. Quality of life in disease-free gastric adenocarcinoma survivors: impacts of clinical stages and reconstructive surgical procedures. Dig Surg 2007;24:59-65. [PubMed]

- Kim YW, Baik YH, Yun YH, et al. Improved quality of life outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 2008;248:721-7. [PubMed]

- Tyrväinen T, Sand J, Sintonen H, et al. Quality of life in the long-term survivors after total gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 2008;97:121-4. [PubMed]

- Wu CW, Chiou JM, Ko FS, et al. Quality of life after curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer in a randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer 2008;98:54-9. [PubMed]

- Tokunaga M, Hiki N, Ohyama S, et al. Effects of reconstruction methods on a patient's quality of life after a proximal gastrectomy: subjective symptoms evaluation using questionnaire survey. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2009;394:637-41. [PubMed]

- Avery K, Hughes R, McNair A, et al. Health-related quality of life and survival in the 2 years after surgery for gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2010;36:148-54. [PubMed]

- Kobayashi D, Kodera Y, Fujiwara M, et al. Assessment of quality of life after gastrectomy using EORTC QLQ-C30 and STO22. World J Surg 2011;35:357-64. [PubMed]

- Jakstaite G, Samalavicius NE, Smailyte G, et al. The quality of life after a total gastrectomy with extended lymphadenectomy and omega type oesophagojejunostomy for gastric adenocarcinoma without distant metastases. BMC Surg 2012;12:11. [PubMed]

- Kim AR, Cho J, Hsu YJ, et al. Changes of quality of life in gastric cancer patients after curative resection: a longitudinal cohort study in Korea. Ann Surg 2012;256:1008-13. [PubMed]

- Kunisaki C, Makino H, Kosaka T, et al. Surgical outcomes of laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a case-control study. Surg Endosc 2012;26:804-10. [PubMed]

- Lee SS, Ryu SW, Kim IH, et al. Quality of life beyond the early postoperative period after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy: the level of patient expectation as the essence of quality of life. Gastric Cancer 2012;15:299-304. [PubMed]

- Namikawa T, Oki T, Kitagawa H, et al. Impact of jejunal pouch interposition reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer on quality of life: short- and long-term consequences. Am J Surg 2012;204:203-9. [PubMed]

- Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou P, et al. The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, 2013. Accesssed on Sep 12th, 2013. Available online: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:e1-34. [PubMed]

- Stern JM, Simes RJ. Publication bias: evidence of delayed publication in a cohort study of clinical research projects. BMJ 1997;315:640-5. [PubMed]