Gastric cancer complicated with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: case report and a brief review

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a group of severe immune function disorders in which the body’s immune system can damage the organs. There are two types of HLH: primary and secondary. Primary HLH mostly arises from inherited immune disorders, and secondary HLH is usually triggered by inflammation, malignant tumor, chemotherapy, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, or infection (1).

Studies of malignant tumors complicated with HLH have mainly focused on hematological malignancies, including lymphoma and leukemia (2). We report two cases of gastric cancer complicated with HLH. To our knowledge, there are no relevant prior published studies of HLH triggered by gastric cancer. We present the following cases in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-432).

Case presentation

Case 1

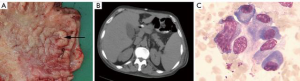

A 68-year-old man was admitted to the Hepatology Department of Peking University People’s Hospital with intermittent fever and anorexia lasting 2 months. The patient’s medical and family histories were unremarkable. Computed tomography (CT) and gastroscopy revealed a tumor at the antrum of the stomach, which biopsy confirmed to be high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. Subsequently, the patient underwent distal subtotal gastrectomy (Figure 1A), and in the first week postoperatively, the patient did not complain of any major discomfort. Postoperative pathology confirmed gastric cancer, which was staged as pT1aN0M0 according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual.

After 1 week, the patient developed an intractable fever with a maximum temperature of 39.1 °C. CT scans and blood tests showed no evidence of hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), syphilis, tuberculosis, bacterial infection, or other complications; however, enlargement of the spleen was indicated (Figure 1B). Therefore, positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) was performed, and cancer recurrence or metastasis was excluded. Bone marrow biopsy indicated hemophagocytosis (Figure 1C). Furthermore, blood tests showed anemia, thrombocytopenia, hypoproteinemia, and a significant increase in the levels of ferritin and soluble CD25 (sCD25) (Table 1). Further, a flow cytometry test showed low natural killer (NK) cell activity. The patient was diagnosed with HLH and was transferred to a specialized hospital for further treatment. After two cycles of the DEP regimen (liposomal doxorubicin 20 mg, for 1 day; etoposide 100 mg, for 1 day; methylprednisolone 20 mg, twice daily for 3 days). The patient remained disease-free for 5 months but eventually died from HLH relapse.

Full table

Case 2

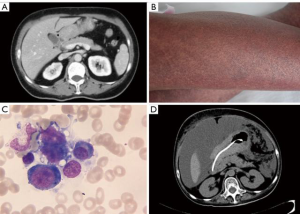

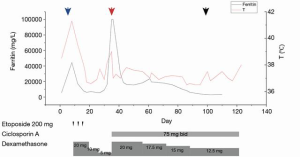

The second patient was a 54-year-old woman who had been diagnosed as having unresectable gastric adenocarcinoma with pyloric obstruction 5 months previously (Figure 2A). After six cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (FOLFOX for two cycles and FOLFIRI for four cycles), the patient was admitted to Peking University People’s Hospital due to an unexplained fever lasting 10 days. On admission, she was pale, with facial edema, and her body temperature fluctuated between 38–41.3 °C. Furthermore, she had progressive, scattered hemorrhagic rashes all over her body (Figure 2B), and petechiae in her mouth. Blood tests indicated anemia, hypothrombinemia, and hypofibrinogenemia, as well as a significant increase in the levels of ferritin and sCD25. Bone marrow biopsy indicated hemophagocytosis (Figure 2C). Laboratory tests showed no evidence of infection. Based on these findings, secondary HLH was confirmed, and chemotherapy based on etoposide (200 mg twice a week) together with dexamethasone (20 mg daily) was subsequently administered.

One week after beginning chemotherapy treatment, the patient’s body temperature returned to normal, and the subcutaneous hemorrhage and body rashes subsided. Blood tests showed an increase in fibrinogen and a decrease in ferritin levels, although pancytopenia was also observed. Considering that the HLH-triggered cytokine storm was under control and the chemotherapy had induced myelosuppression, etoposide administration was terminated after 3 treatments, and dexamethasone was tapered (10 mg daily for 1 week, then 5 mg daily).

Two weeks after regimen adjustment, the patient’s fever, facial edema, and skin rash returned, indicating relapse of HLH. Because of their effects on inhibiting HLH and stimulating bone marrow, dexamethasone (20 mg daily) and cyclosporine (75 mg twice daily) were administered. Five days later, the patient’s condition stabilized. Considering the pancytopenia, cyclosporine (75 mg twice daily) was continuously administered, but chemotherapy, such as etoposide and docetaxel (salvage therapy for HLH) was no longer given. Moreover, the dose of dexamethasone was reduced (17.5 mg daily for 2 weeks, 15 mg daily for 2 weeks, followed by 12.5 mg daily). During this period, the patient’s condition was stable, and the pancytopenia and hyperferritinemia showed progressive decline.

The patient remained in a stable condition for 8 weeks, but then ascites and bloody stools returned. CT showed a peritoneal metastasis lesion (Figure 2D). The patient underwent symptomatic therapy; however, the hypoproteinemia and electrolyte disturbance could not be corrected. She gradually progressed to renal failure and eventually died from multiple organ failure.

Ethical statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Discussion

Secondary HLH, also known as acquired HLH, is associated with infectious, oncologic, chemotherapeutic, and other underlying causes (1). Here, we reported two cases of gastric cancer complicated with HLH. The 2004 HLH diagnostic criteria and the results of the two patients are presented in Table 1.

Epidemiology

The available epidemiologic data on HLH are limited. HLH has an estimated annual incidence of 1 per 800,000 people in Japan (3) and less than 10 per 1 million children in Italy, Sweden, and the United States (4-6). Solid tumor-associated HLH is even rarer. For instance, in a study of 2,197 adults with HLH, only 1.46% of patients had HLH triggered by a solid tumor (7).

However, the incidence of HLH secondary to a solid tumor may be underestimated. Intractable fever is common in cancer patients, especially in those who undergo chemotherapy. Early studies considered cancer to be the cause of fever in 15–20% of cases of fever of an unknown origin (8), and such cases were characterized as a neoplastic fever. However, HLH may be behind cases of neoplastic fever. Furthermore, immunotherapeutic strategies have been used recently to treat several malignancies, and previous studies have suggested that HLH may occur as a result of immunotherapy (1). One literature review includes 16 reports involving a total of 20 patients who were diagnosed with HLH secondary to a solid tumor (Table 2). Among the patients, 8 received immune checkpoint inhibitors (16-18,20-24), 8 underwent chemotherapy (11-14), and 4 were only diagnosed with a solid tumor (9,10,15,19). Thus, the application of immunotherapy as well as some HLH patients who are misdiagnosed as neoplastic fever may increase the incidence of HLH, which requires more attention.

Full table

Pathophysiology

Based on the pathophysiology of primary HLH, defective granule-mediated cytotoxicity of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and NK cells is known to be the main cause of HLH (17). The inability of NK cells or CTLs to down-regulate the immune response results in a significant inflammatory response triggered by hypersecretion of cytokines, including interferon-γ, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and IL-12. This so-called cytokine storm could be pathogenically related to the development of HLH, thereby resulting in significant tissue damage and organ failure (7).

The exact underlying mechanism of HLH secondary to a solid tumor has yet to be elucidated. It is assumed that the hyperinflammation is triggered by the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and persistent antigen stimulation by tumor cells. Further, the imbalance of immune homeostasis induced by chemotherapy and the underlying malignancy would lower the threshold for triggering HLH (2).

Treatment and prognosis

Neither the low incidence of solid tumor-associated HLH nor the lack of relevant related studies should exclude HLH from being considered in cancer patients, especially as early diagnosis and treatment are required due to the poor prognosis and high mortality. Both patients in the present study as well as five patients reported in the literature have died.

In the treatment of HLH, early diagnosis and intervention are crucial (1). The most common symptoms of HLH include intractable fever, erythema, and subcutaneous bleeding (25). When these symptoms are present in a cancer patient, especially those undergoing chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, screening tests including sCD25, ferritin, NK cell activity, and bone marrow biopsy need to be considered at an early stage in order to diagnose HLH as soon as possible.

Gastric cancer associated with HLH is challenging to cure. Treatment for solid tumor-associated HLH should take into account the primary tumor, patient status, organ function, and anti-neoplastic therapies (25). There is a lack of relevant trials to guide the treatment of cancer patients with HLH. The immunosuppressive agents used in the treatment of HLH mainly include glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, etoposide and doxorubicin (26,27). Among these agents, glucocorticoids are as always the initial treatment and are used in most regimens, and others drugs are from the 1994 and 2004 HLH protocols, or CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) and DEP (doxorubicin, etoposide, and methylprednisolone) regimens. CHOP is mostly used for lymphoma-associated HLH, and DEP is used as a salvage therapy (27). As in case 2, we applied a regimen including etoposide and dexamethasone, which was mainly based on the 2004 HLH protocol (25). Etoposide eliminates activated immune cells to calm the cytokine storm (28), but its long-term usage may cause bone marrow suppression. Moreover, etoposide also serves as palliative chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer, and has been found beneficial for curing both HLH and cancer. The main challenge is assessing the fine balance between the potential benefits of suppressing inflammatory cytokines and the detrimental effect of myelosuppression.

If possible, resection of the primary tumor is a treatment option, although it does not eliminate HLH relapse (as seen in case 1). In our experience, once HLH relapsed, the poor status of the patient imposes great restrictions on treatment, thus increasing the risk of death. Therefore, properly extending immunosuppressive therapy could reduce the risk of HLH recurrence, even though the primary tumor may progress without resection and cause death (as seen in case 2).

Monitoring the treatment effect is crucial. In case 2, we monitored the fever curve, ferritin and sCD25 levels, liver function tests, and fibrinogen to determine the treatment response. Our data showed that the ferritin levels were correlated with disease activity (Figure 3), which matched the experience of other authors (29).

Solid tumor-associated HLH has a low incidence but high mortality. In this report, we showed that secondary HLH is associated with gastric cancer, not only during the late stage, but also at an early stage. Therefore, more attention and additional research are needed to bring benefits to patients with solid tumors complicated with HLH.

Conclusions

Although solid tumor-associated HLH is rare, it is still a concern. Recognizing the typical symptoms in patients undergoing chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy could significantly accelerate early diagnosis and help determine a treatment regimen. The prognosis of patients with uncontrolled primary disease is extremely poor. Therefore, more attention should be paid to solid tumor-associated HLH to improve the prognosis of patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the families of the patients for allowing us to share the details of their cases.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-432

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-432

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-20-432). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Tamamyan GN, Kantarjian HM, Ning J, et al. Malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: Relation to hemophagocytosis, characteristics, and outcomes. Cancer 2016;122:2857-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Daver N, McClain K, Allen CE, et al. A consensus review on malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Cancer 2017;123:3229-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ishii E, Ohga S, Imashuku S, et al. Nationwide survey of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in Japan. Int J Hematol 2007;86:58-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henter JI, Elinder G, Söder O, et al. Incidence in Sweden and clinical features of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Acta Paediatr Scand 1991;80:428-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aricò M, Danesino C, Pende D, et al. Pathogenesis of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol 2001;114:761-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Niece JA, Rogers ZR, Ahmad N, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in Texas: observations on ethnicity and race. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2010;54:424-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, et al. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet 2014;383:1503-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zell JA, Chang JC. Neoplastic fever: a neglected paraneoplastic syndrome. Support Care Cancer 2005;13:870-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jiwnani S, Karimundackal G, Kulkarni A, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome complicating lung resection. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2012;20:341-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Declerck L, Adenis C, Amela E, et al. Prostate cancer related haemophagocytic syndrome: successful treatment with chemotherapy. Acta Oncol 2012;51:268-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schwarz L, Bridoux V, Veber B, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome: an unusual and underestimated complication of cytoreduction surgery with heated intraperitoneal oxaliplatin. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:3919-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murphy EP, Mo J, Yoon JM. Secondary Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in a Patient With Favorable Histology Wilms Tumor. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2015;37:e494-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ciccarese C, Ferrara R, Fantinel E, et al. Acquired hemophagocytic syndrome in a patient with synovial sarcoma: a case report. Future Sci OA 2015;1:FSO29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nascimento FA, Nery J, Trennepohl J, et al. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis After Initiation of Chemotherapy for Bilateral Adrenal Neuroblastoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2016;38:e13-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stabler S, Becquart C, Dumezy F, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res 2017;27:377-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hantel A, Gabster B, Cheng JX, et al. Severe hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a melanoma patient treated with ipilimumab + nivolumab. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sadaat M, Jang S. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with immunotherapy: brief review and case report. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sasaki K, Uehara J, Iinuma S, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with dabrafenib and trametinib combination therapy following pembrolizumab administration for advanced melanoma. Ann Oncol 2018;29:1602-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wakefield C, Mehta PA, Corathers S, et al. A First Report of Secondary Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis Associated With Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2018;40:e97-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okawa S, Kayatani H, Fujiwara K, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia and Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Intern Med 2019;58:699-702. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al-Samkari H, Snyder GD, Nikiforow S, et al. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis complicating pembrolizumab treatment for metastatic breast cancer in a patient with the PRF1A91V gene polymorphism. J Med Genet 2019;56:39-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lorenz G, Schul L, Bachmann Q, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis secondary to pembrolizumab treatment with insufficient response to high-dose steroids. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58:1106-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akagi Y, Awano N, Inomata M, et al. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in a Patient with Rheumatoid Arthritis on Pembrolizumab for Lung Adenocarcinoma. Intern Med 2020;59:1075-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mizuta H, Nakano E, Takahashi A, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with advanced malignant melanoma accompanied by ipilimumab and nivolumab: A case report and literature review. Dermatol Ther 2020;33:e13321 [PubMed]

- Daver N, Kantarjian H. Malignancy-associated haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:169-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48:124-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hayden A, Park S, Giustini D, et al. Hemophagocytic syndromes (HPSs) including hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) in adults: A systematic scoping review. Blood Rev 2016;30:411-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zinter MS, Hermiston ML. Calming the storm in HLH. Blood 2019;134:103-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schram AM, Berliner N. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the adult patient. Blood 2015;125:2908-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]