Comparison of characteristics between true rectal neuroendocrine tumors and rectal hyperplastic polyps among patients with endoscope-diagnosed rectal neuroendocrine tumors

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumor [NET/neuroendocrine neoplasm (NEN)] is a malignant tumor originating from neuroendocrine cells and peptidergic neurons (1). With the widespread use of high-definition endoscopy and extensive screening of colorectal cancer, the diagnosis rate of rectal neuroendocrine tumors (rectal neuroendocrine neoplasms; rNENs) is increasing. A global epidemiology study reported that the incidence rates of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs) are rising steadily in North America, Asia, and Europe, though this rise appears to be most profound in North America (2). Recent studies have shown that the incidence of NEN is 5.86/10,000 (3,4). According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, gastrointestinal and pancreatic NEN accounts for 58% of all NEN, of which 17.2% occur in the rectum (5,6). The incidence of age-adjusted rNENs has increased by about 10 times in the past 35 years (7).

Under white light endoscopy, lesions that display mound-like submucosal eminence, yellow penetration, hard texture, and smooth surface or ulcerated features are suspected rNENs cases. The possibility of rNENs is considered when endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) examination shows lesions that are round or oval, hypoechoic or moderately homogeneous, with a clear boundary, and mainly originating from layer 2 (Muscularis mucosae) and/or layer 3 (Submucosa) (8). It has previously been reported that when rNENs had been suspected under endoscope, the final pathological results have shown stromal tumor, leiomyoma, lymphoma, metastatic cancer, inflammatory nodule, polyp, and so on (9,10). In general, rNENs are well differentiated small tumors with a fairly good prognosis, but they also show variations of larger tumor size, metastasis, and severe prognosis (11). A case report found that radiology of a low-grade rNEN in a 36-year-old male revealed a suspected 2.6 cm mesenteric lymph node metastasis and multiple left internal iliac lymph node metastases (12).

Rectal hyperplastic polyp (rHP) is a benign non-neoplastic disease of epithelial origin, with an incidence of about 10% (13), which is much higher than that of rNENs. Under endoscopic examination, rHP shows the same color as the surrounding mucosa or a white, smooth surface and clear boundary. Generally, rHP only needs endoscopic follow-up.

For rNENs with a diameter of 5–10 mm, the endoscopic findings are atypical and some of them are similar to rHP. According to previous reports, it is uncommon for rNENs to be misdiagnosed as rHP, and endoscopic polypectomy most often reveals a positive basal margin and residual lesions (14-16). Similar findings have been reported in other gastrointestinal tumors. Giotis et al. (17) reported a case of duodenal-type follicular lymphoma in the rectum appearing as a hyperplastic polyp of duodenum and stomach, of which a similar case had never been previously reported.

However, the misdiagnosis of rHP as rNENs has not been reported in the literature in the past, but because of the collection of cases, only 8 cases were diagnosed as rHP by endoscope, the sample is relatively small, and there will be a little bias in statistics. Only this report is used to alert clinicians to the possibility of overtreatment.

In this study, we performed a review of 103 cases of endoscopic examinations of suspected rNENs in our center, of which 8 cases of rHP had been misdiagnosed as rNENs, and subsequently analyzed their endoscopic features. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-22-369/rc).

Methods

Patient population

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Ethical approval and individual consent for this retrospective analysis were waived by the Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University. We conducted a retrospective analysis (cross-sectional comparative study) of 245 cases of rectal submucosal eminence diagnosed by endoscopy in our hospital from January 2015 to December 2020.

Patients with endoscopic diagnosis of rNENs were included; the exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) postoperative pathological diagnosis of stromal tumor, lipoma, and other lesions; (II) the pathological diagnosis could not be obtained without treatment; (III) incomplete clinical data.

The extracted data included the size, shape, vasodilation, color, and boundary of the lesions under white light endoscope, and the size, source level, and echo of the lesions, and whether the boundary of the lesions was clear or not under EUS.

Preoperative evaluation methods

All patients with suspected rNENs and lesions larger than 1 cm underwent chest, abdominal, and pelvic computed tomography (CT) or B-ultrasound before operation. If there were no metastatic lymph nodes, or liver and lung metastases, endoscopic resection was performed.

Operation

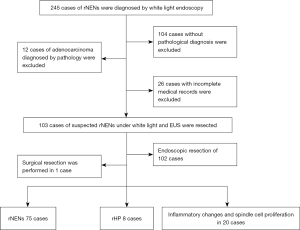

A total of 103 patients underwent endoscopic or surgical resection based on the final pathological diagnosis (Figure 1). The rNENs endoscopic curative resection standard was employed: G1/G2, the tumor was confined to the mucous membrane and submucosa, there were no residual tumor cells at the base and horizontal cutting edge, and no lymphatic vascular invasion (14).

Pathological criteria

Pathological diagnosis was performed by a senior pathologist by review of the pathological sections of all patients. According to the rNENs pathological diagnostic criteria (18), the tumor was graded into G1, G2, and G3 according to the proliferative activity (evaluated by mitotic image number or Ki-67 positive index). Immunohistochemical (IHC) markers such as synaptophysin (Syn), chromaffin granule protein (CgA), and neuron specific enolase (NSE) were also analyzed to assist the pathological diagnosis of rNENs.

Statistical analysis

The endoscopic features of the cases were analyzed. The collected data were statistically analyzed with the software SPSS 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Measurement data were expressed by mean ± standard deviation (), and counting data were tested and analyzed by χ2 test and Fisher’s exact probability method. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall characteristics

Among the participants, 103 cases of rNENs were diagnosed by both white light endoscopy and EUS. All cases underwent lesion resection and obtained the final pathological diagnosis. Among them, rNEN was found in 75 cases, rHP in 8 cases, and the other 20 cases displayed inflammatory changes and spindle cell proliferation (Figure 1). There were 44 females and 59 males with an average age of 47.18±10.57 years, and the average size of the lesion was 0.2–2.0 cm. A total of 54 cases were examined by colonoscopy because of abdominal pain, change of stool habit, hematochezia, and other focal symptoms. No carcinoid syndrome was found in all patients with rNENs. Among the 75 cases of rNENs (72.8%), G1 stage accounted for 96% (n=72) and G2 accounted for 4.0% (n=3).

Clinical features

The average age of the patients in this study was (46.84±10.75) years, and the ratio of male to female was 1.37. The clinical symptoms were not specific. Most cases showed changes in defecation habits, abdominal pain, and physical examination. There was no statistical difference in age, gender, and clinical manifestations between the 2 groups. The details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| Clinical features | rNEN (N=75) | rHP (N=8) | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 44 | 4 | 0.223 | 0.716 |

| Female | 31 | 4 | ||

| Clinical manifestation | ||||

| Abdominal pain & change of stool pattern | 8 | 2 | 4.783 | 0.317 |

| Change of stool pattern | 24 | 1 | ||

| Hemafecia | 3 | 0 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 17 | 3 | ||

| Health examination | 20 | 1 | ||

| Rests | 3 | 1 |

rNENs, rectal neuroendocrine tumors; rHP, rectal hyperplastic polyp.

Endoscopic features

Among the 75 cases of pathologically confirmed rNENs, distribution in the lower half of the rectum (≤10 cm) was the most common (94.7%), with a diameter of 0.2–2.0, most of them were within 1.0 cm (93.3%), and 6 cases were greater than 1.0 cm; the pathological grade was G1 (n=72, 75.96%), endoscopic resection was performed in 74 cases, and surgical resection was performed in 1 case.

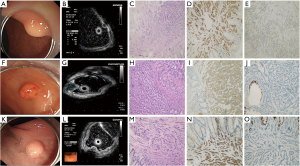

During the follow-up period from endoscopic therapy to December 2020, all 75 cases survived without recurrence or metastasis. The endoscopic manifestation is shown in Figure 2.

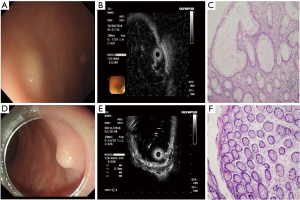

A total of 28 cases were misdiagnosed. The endoscopic findings of misdiagnosed rHP are shown in Table 2 and Figure 3 below. The final pathological results of misdiagnosed cases were rHP 8 (n=8), chronic inflammatory change (n=13), spindle cell hyperplasia (n=4), and rectal tubular adenoma (n=3).

Table 2

| Case | White light endoscopy | EUS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter (cm) | Shape | Superficial vascular proliferation | Color | Boundary | Layer | Echo | Boundary | ||

| 1 | 0.6×0.4 | Flat | No | Yellowish White | Unclear | 1, 2 | Hypo | Unclear | |

| 2 | 0.7×0.8 | Hump | Yes | Yellowish White | Part of visible | 1, 2 | Medium | Clear | |

| 3 | 1.0×1.0 | Arch | No | Yellowish White | Part of visible | 1, 2 | Hypo | Clear | |

| 4 | 0.8×0.5 | Flat | No | Yellowish White | Part of visible | 2 | Hypo | Unclear | |

| 5 | 0.5×0.4 | Flat | No | Yellowish White | Part of visible | 1, 2 | Medium | Unclear | |

| 6 | 0.5×0.6 | Hump | No | Red | Unclear | 1, 2 | Medium | Clear | |

| 7 | 0.5 | Hump | No | Yellowish white | Part of visible | 1, 2 | Medium | Clear | |

| 8 | 0.5 | Flat | Yes | Yellowish white | Unclear | 2 | Hypo | Unclear | |

rHP, rectal hyperplastic polyp; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound.

There was no significant difference between rNENs and rHP in terms of gender, age, clinical manifestation, shape and color of lesions, dilated vessels on the surface, and location of lesions under white light endoscope; there were significant differences in whether the boundary of lesions was clear under white light endoscopy, the origin and echo of lesions under EUS, and whether the boundaries were clear or not (Table 3).

Table 3

| Endoscopy | Characteristic | Feature | rNEN (N=75) | rHP (N=8) | χ2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White light endoscopy | Shape | Flat | 41 | 4 | 0.533 | 0.874 |

| Hump | 27 | 3 | ||||

| Arch | 7 | 1 | ||||

| Color | Red | 1 | 1 | 3.646 | 0.218 | |

| The same | 9 | 0 | ||||

| Yellowish white | 65 | 7 | ||||

| Superficial vascular proliferation | Yes | 26 | 2 | 0.302 | 0.711 | |

| No | 49 | 6 | ||||

| Boundary | Clear | 8 | 0 | 10.248 | 0.006 | |

| Part of visible | 8 | 5 | ||||

| Unclear | 59 | 3 | ||||

| From the anus | Low | 18 | 2 | 5.567 | 0.063 | |

| Middle | 53 | 4 | ||||

| High | 4 | 2 | ||||

| EUS | Layer | 1 | 1 | 0 | 12.445 | 0.004 |

| 2 | 60 | 2 | ||||

| 1&2 | 13 | 6 | ||||

| 2&3 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Echo | Hypo | 71 | 4 | 16.559 | 0.002 | |

| Medium | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Boundary | Clear | 63 | 0 | 5.370 | 0.041 |

rNENs, rectal neuroendocrine tumors; rHP, rectal hyperplastic polyp; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound.

G2 rNENs and rHP

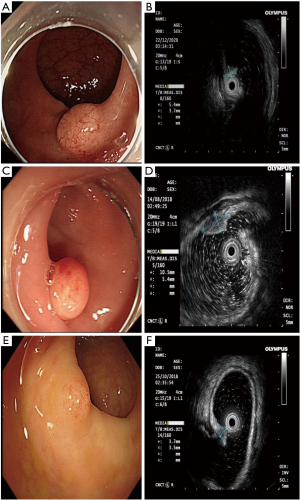

There was no correlation between G2 rNENs and rHP, as shown in Table 4. Under white light endoscope, there are a large number of dilated blood vessels on the surface of rNENs compared with those in rHP, G2, as shown in Figure 4.

Table 4

| Endoscopy | Characteristic | Feature | G2 (N=3) | rHP (N=8) | χ2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White light endoscopy | Shape | Flat | 0 | 4 | 3.000 | 0.273 |

| Hump | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Arch | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Color | Red | 1 | 1 | 1.727 | 0.491 | |

| Yellowish white | 2 | 7 | ||||

| Superficial vascular proliferation | Yes | 3 | 2 | 4.950 | 0.061 | |

| No | 0 | 6 | ||||

| Boundary | Part of visible | 0 | 5 | 3.438 | 0.182 | |

| Unclear | 3 | 3 | ||||

| From the anus | Low | 0 | 2 | 1.727 | 0.491 | |

| Middle | 3 | 4 | ||||

| High | 0 | 2 | ||||

| EUS | Layer | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4.950 | 0.061 |

| 1&2 | 0 | 6 | ||||

| 2&3 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Echo | Hypo | 3 | 4 | 2.357 | 0.236 | |

| Medium | 0 | 4 | ||||

| Boundary | Clear | 3 | 4 | 2.357 | 0.236 | |

| Unclear | 0 | 4 |

rNENs, rectal neuroendocrine tumors; rHP, rectal hyperplastic polyp; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound.

Discussion

According to the guidelines of the European Society of Neuroendocrine Oncology and the consensus of China (17,19,20), preoperative evaluation of rNENs is essential. White light endoscopy combined with EUS can evaluate the size of the tumor, the depth of invasion, and the existence of lymph node invasion to determine the appropriate follow-up treatment. At the same time, it is suggested to implement abdominal CT and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination to exclude metastasis. At present, in the treatment of rNENs, endoscopic resection is performed when the diameter is less than 1 cm, the lesion is limited to mucosa and submucosa, and there are no other high-risk factors. Endoscopic treatment can be considered when the lesions are under 2 cm.

Endoscopic rNENs have certain characteristics (21), usually displaying hemispherical or mound-shaped wide base eminence, yellowish or grayish white, clear boundaries, hard texture of biopsy forceps, smooth surface mucosa, and visible capillaries. An EUS can evaluate the primitive layer, internal parenchyma echo uniformity, and lesion echo of submucosal tumors (SMT) (22). Most of them are situated in the first and/or second and third layers of the lesion source, with low or medium-low echo, uniform internal echo, and clear boundary, which is consistent with the results of this study.

In this study, 8 cases of rHP were misdiagnosed as rNENs, all of which were located in the middle and low rectum, the color was yellow or white under white light endoscope, and the boundaries were unclear. The EUS showed that they mostly originated from layer 1 and 2 and were hypoechoic; 4 cases had clear boundaries, which was very similar to that of rNENs, and was the cause of endoscopic misdiagnosis.

In a Korean study, it was reported that the diagnosis rate of rNENs in colonoscopic screening was 0.17%, which was much lower than the incidence of adenomas and hyperplastic polyps (23). Most rNENs showed small, round, smooth, polyp-like protuberances covered with normal mucosa, which made it difficult to differentiate from other colorectal polyps (24-26). Between 80% and 92% of rNENs had a diameter of <1 cm at the first endoscopic diagnosis (25), which made misdiagnosis or even missed diagnosis easy because of the small lesion size. Cha et al. reported that 9.3% of rNENs were misdiagnosed as polyps and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) resulted in residual lesions (27).

There has been no previous report of rHP misdiagnosed as rNENs. Also known as metaplastic polyp, rHP is a common benign non-tumor proliferative polyp displaying single or multiple, endoscopic gray-white or homochromatic, well-defined polyps. None of the 8 cases of rHPs reported in this paper had a completely clear boundary, and EUS detected that they originated from layers 1 and 2, which may be related to the mode of growth.

In this study, it was found that part of the rHP has a smooth surface, the boundary is not clear, and the EUS came from the first or second layer, so care must be taken to distinguish it from rNENs. Cha JH, (27) asserted that rNENs suspected by endoscope should be biopsied before endoscopic resection. However, the opinions of researchers differ regarding whether rNENs should be biopsied or not. Meriam et al. (15) contemplated that preoperative biopsy was the reason lesions could not be removed completely under endoscope, so they proposed that for the lesions suspected of rNENs, preoperative biopsy should not be performed, but EMR or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) should be performed directly. Since the size of rNENs focus is small, and most of the tumors are located in the deep layer of mucosa or submucosa, some endoscopic biopsies are superficial, making it difficult to obtain pathological results with diagnostic value, which can easily lead to misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis (28).

Due to its good prognosis, rHP can be followed up without endoscopic resection. Endoscopic resection may lead to misdiagnosis as rNENs, which not only increases the medical cost, but also the risk of complications. Therefore, preoperative diagnosis is particularly important. A total of 8 cases of rHP were misdiagnosed as rNENs I this study, the main causes of which were yellow and white appearance under endoscope and unclear boundary. Therefore, we believe that biopsy is meaningful when it is difficult to differentiate, and lesions of rHP and other epithelial sources can be excluded. With the progress of endoscopic technology, adhesion after biopsy has little effect on follow-up endoscopic resection.

From reviewing these misdiagnosed cases, we can draw some experiential conclusions: (I) rNEN is the most common clinical submucosal eminence of rectum, and the endoscopic findings of most cases are similar to rHP and lead to a more subjective diagnosis. (II) the boundary of the lesion should be carefully observed, especially when it is found that part of the boundary is clear. For example, of the 8 cases of rHP in this study, partial boundaries could still be seen in 5 cases, and biopsy is feasible when it is difficult to differentiate. (III) the experience and operation of endoscopists are also related to the accuracy of diagnosis.

This study included 3 cases of G2 stage, whether there were dilated blood vessels on the lesion surface under white light endoscope, and there was no statistical significance between the source level of EUS. Due to the small number of samples included, further study is needed.

This was a retrospective single-center study, with some limitations: the number of study cases was small, which may have affected the results. In future, a large sample, multi-center, prospective study is needed to verify the above conclusions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This reserch was supported by Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects-Qiankehe Foundation (No. ZK2022-General-443).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-22-369/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-22-369/dss

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-22-369/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Ethical approval and individual consent for this retrospective analysis were waived by the Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Cui M, Wei JG, Xu CW, et al. Clinicopathological analyses of gastric neuroendocrine tumor misdiagnosis as gastric adenocarcinoma. Journal of Clinical and Pathological Research 2015;35:2023-6.

- Das S, Dasari A. Epidemiology, Incidence, and Prevalence of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Are There Global Differences? Curr Oncol Rep 2021;23:43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fraenkel M, Faggiano A, Valk GD. Epidemiology of Neuroendocrine Tumors. Front Horm Res 2015;44:1-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guo LJ, Wang CH, Tang CW. Epidemiological features of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in Chengdu city with a population of 14 million based on data from a single institution. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2016;12:284-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer 2003;97:934-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, et al. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1335-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Modlin IM, Oberg K, Chung DC, et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:61-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Angelis C, Carucci P, Repici A, et al. Endosonography in decision making and management of gastrointestinal endocrine tumors. Eur J Ultrasound 1999;10:139-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu JJ, Cheng HT, Cheng LH, et al. Diagnostic value of endoscopic ultrasonography in 33 cases of rectal neuroendocrine tumors. Chinese Journal of Digestion 2014;34:627-8.

- Malire Y, Gulibahaer S, Zhang ZQ, et al. Endoscopic diagnosis and therapies of rectal neuroendocrine tumors. China Journal of Endoscopy 2020;26:31-7.

- Marincas AM, Prunoiu V, Bratucu E, et al. Rectal Neuroendocrine Tumour with an Aggressive Behaviour. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2021;116:368-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shin S, Maeng YI, Jung S, et al. A small, low-grade rectal neuroendocrine tumor with lateral pelvic lymph node metastasis: a case report. Ann Coloproctol 2022; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, et al. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology 2020;76:182-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guo X, Wang XD, Linghu EQ, et al. The role of mini-probescanner in the diagnosis and treatment of rectal smooth protuberant lesions. Chinese Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2014;23:471-3.

- Meriam S, Trad D, Jouini R, et al. Rectal neuroendocrine tumor presenting as a polyp with hepatic metastases. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;90:688-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim SH, Park CH, Ki HS, et al. Endoscopic treatment of duodenal neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Endosc 2013;46:656-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giotis I, Tribonias G, Zacharopoulou E, et al. A rare case of duodenal-type follicular lymphoma in rectum appearing as hyperplastic polyp with metachronous appearance in duodenum and stomach. Clin J Gastroenterol 2021;14:1632-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramage JK, De Herder WW, Delle Fave G, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Colorectal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology 2016;103:139-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Consensus on pathological diagnosis of gastrointestinal and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in China (2020). Chinese Journal of Pathology 2021;50:14-20. [PubMed]

- Caplin M, Sundin A, Nillson O, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms: colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology 2012;95:88-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Surgery Group of Digestive Endoscopy Branch of Chinese Medical Association. digestive Endoscopy Professional Committee of Endoscopist Branch of Chinese Medical Association, Gastrointestinal Surgery Group of Surgery Branch of Chinese Medical Association. Expert consensus on endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal submucosal tumors in China (2018). Chinese Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2018;21:841-52.

- Sato Y. Clinical features and management of type I gastric carcinoids. Clin J Gastroenterol 2014;7:381-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okanobu H, Hata J, Haruma K, et al. A classification system of echogenicity for gastrointestinal neoplasms. Digestion 2005;72:8-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jung YS, Yun KE, Chang Y, et al. Risk factors associated with rectal neuroendocrine tumors: a cross-sectional study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014;23:1406-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chablaney S, Zator ZA, Kumta NA. Diagnosis and Management of Rectal Neuroendocrine Tumors. Clin Endosc 2017;50:530-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scherübl H. Rectal carcinoids are on the rise: early detection by screening endoscopy. Endoscopy 2009;41:162-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cha JH, Jung DH, Kim JH, et al. Long-term outcomes according to additional treatments after endoscopic resection for rectal small neuroendocrine tumors. Sci Rep 2019;9:4911. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang HF, Feng YC, Ma Y. 26 signs and their clinical value in diagnosis of rectal neuroendocrine neoplasms. Journal of Colorectal & Anal Surgery 2016;22:246-9.