ARID1A is involved in DNA double-strand break repair in gastric cancer

Highlight box

Key findings

• Our findings indicate that ARID1A could serve as a therapeutic target and biomarker for gastric cancer (GC) patients.

What is known and what is new?

• ARID1A expression in GC tissues is negatively correlated with the invasion depth of tumors, pathological differentiation, and lymph node metastasis, which suggests that ARID1A plays a role in GC development.

• Our study found that ARID1A could participate in DNA damage repair. Further, ARID1A was also found to be involved in and suppress GC proliferation and invasion, and to promote GC apoptosis.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Further studies on ARID1A must discuss whether ARID1A is a valuable biomarker for the prognosis and targeted therapy of GC.

Introduction

In eukaryotic cells, defects in DNA damage repair can result in genetic mutations, which in turn can result in the advancement of diverse kinds of cancers. Thus, DNA damage repair mechanisms need to be explored to ensure gene stability and reveal disease progression.

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes (1), chromatin remodeling and deacetylase complexes, and histone covalently modified complexes regulate gene expression and chromatin structure (2). Research has shown that the switch/sucrose nonfermentable chromatin-remodeling complex (SWI/SNF) complex is mutated in 19.6% of human cancers (3). The SWI/SNF complex is a multi-subunit chromatin remodeling complex that regulates gene expression by relocating nucleosomes using ATP hydrolysis (4). ARID1A is a core subunit of SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, which has a high mutation rate in various types of cancer and is considered as a tumor suppressor gene (5).

ARID1A is a gene that encodes the ARID1A protein and is found on human chromosome 1p36.11 (6). The N-terminus of ARID1A includes an AR domain, with approximately 100 amino acids, and can bind non-specifically to AT-rich DNA sequences (7). The C-terminal LXXLL motif of ARID1A contains several binding sites that interact with glucocorticoid receptors (8). Research has shown that gastric cancer (GC) patients with low ARID1A expression have a short survival time (9).

In a recent study, it is suggested that ARID1A plays important roles to promote DNA double-strand breaks repair pathways, but its detailed mechanism of action remains to be explored (10). This study attempts to explore whether ARID1A is involved in the process of DNA damage repair and whether ARID1A is associated with the occurrence and development of GC. More specifically, this study explores the mechanism of ARID1A regulation on proliferation, migration, apoptosis, and DNA damage repair in gastric adenocarcinoma cell lines. We present this article in accordance with the MDAR reporting checklist (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-283/rc).

Methods

Cell culture

Human GC cell lines were acquired from the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. SGC-7901 and AGS cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 U/mL). Cells in the logarithmic growth phase were digested with trypsin (Sangon Biotech Co., Shanghai, China) and resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium at a density of [3–5]×104 cells/mL.

Transfection of siRNA and plasmids

After the culture reached 70–90% confluence, the inoculated cells were subjected to plasmid transfection using the PolyJet DNA transfection reagent (SignaGen Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). After the culture reached 30–50% confluence, short-interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection was performed using the GenMute siRNA transfection reagent (SignaGen Laboratories). pcDNA6-ARID1A was provided by Addgene (Cambridge, MA, USA). The sequence of the ARID1A siRNA was CAGCUUGCCUGAUCUAUCUTT, and was provided by from RiboBio Company (Guangzhou, China).

Western blotting

Protein samples were collected after etoposide (ETO) treatment. The proteins were subjected to traditional sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis after being treated with the Laemmli 2× Concentrate (S3401; Sigma, Victoria, BC, Canada) buffer cleavage and heated in a 100-degree metal bath for five minutes. The proteins were then transported to the nitrocellulose (NC) membrane (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) with 5% skim milk. The cells were blocked for 1 hour at ambient temperature and then incubated using the corresponding primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. The cells were rinsed three times with tris-buffered saline with Tween-20, 10× (TBST), and then incubated with the secondary antibody for the same period, after which they were washed again with TBST. The protein band was detected using an Amersham Imager 600 System (AI600, General Electric Company, Boston, USA) chemiluminescence imager.

Extraction of RNA and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

The total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using the Prime-Script RT Reagent Kit (Perfect Real Time, TaKaRa, Kyoto, Japan). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal control gene and the fold induction was calculated using the 2–DDCT formula. The quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed with a SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa, Japan. Inc. Catalog Number DRR041A) (PCR protocol: stage 1: early denaturing, repeat: 1; 95 °C 30 s. Stage 2: PCR reaction, repeat: 40; 95 °C 5 s; 60 °C 30 s. Stage 3: melt curve: 95 °C 15 s; 60 °C 60 s; 95 °C 15 s). The following primers were used: ARID1A (F) 5'-CTTCAACCTCAGTCAGCTCCCA-3', ARID1A (R) 5'-GGTCACCCACCTCATACTCCTTT-3', GAPDH (F) 5'-GGTGGTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACA-3', and GAPDH (R) 5'-GTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTCGTTGT-3'. GAPDH served as an endogenous control. Each sample was repeated in triplicate.

Methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) assays

The cells were seeded in 96-well culture plates at a density of 5×104 cells/mL (180 µL per well). After the cells of the experimental group were completely grown, they were treated with ETO interferes with the ability of topoisomerase II to reconnect nicks in DNA strands, causing DNA double strand breaks). Different concentrations of ETO (6.125, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µM) AGS and SGC-7901 cells were treated for 24 h, and the effect of ETO on cell survival was observed. During the treatment, MTT (5 mg/mL, 20 µL) was added to the cells, and the culture continued for four hours, after which the culture solution was aspirated. Next, 150 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to each well, and absorbance was evaluated at 490 nm after shaking for 10 minutes. The cell inhibition rate was calculated as follows:

Comet assays

Before being applied to the OxiSelect 96-Well Comet Slide (Cell Biolabs, Inc., San Diego, USA; Catalog Number STA-355), individual cells were combined with molten agarose. The DNA in these implanted cells was then denatured and relaxed using an alkaline solution and lysis buffer. Finally, the samples were separated into intact and damaged DNA fragments by electrophoresis in a horizontal chamber. The samples were dried and then stained using DNA dye and observed by epifluorescence microscopy after electrophoresis. Under these conditions, damaged DNA (including strand breaks and cleavage) moved further than undamaged DNA, forming a “comet tail” structure.

Immunofluorescence assays

The cells were seeded into aseptic slides. 100 µM of ETO was added to the AGS cells for 24 hours. The cells were subjected to fixation with paraformaldehyde (4%) and then permeabilized using Triton X-100 (0.25%) (×100, Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) for 5 minutes. The cells were then blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin. After which, the cells were incubated with the targeting antibodies ARID1A (#12354s; Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, USA) and γH2AX (#2577s; Cell Signaling Technology). Next, the cells were incubated with AlexaFluor® 594 (red) (#8889s, Cell Signaling Technology) or AlexaFluor® 488 (#4412s; Cell Signaling Technology) as the secondary antibody. 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (#4083s; Cell Signaling Technology) was used to stain cellular nuclei. Finally, fluorescence was visualized with a fluorescence microscopy (Leica TCS SP8; Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany).

Wound-healing assays

ARID1A and pcDNA3.1 were transfected at 80% density into cells seeded into six-well plates. After 24 hours, sterilized yellow nuclease-free primer (200 µL) was used to draw a line on the cell layer surface. Floating cells were washed out. The cells were treated with drugs after being starved with serum-free Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium. The cells were imaged at 0, 24, and 48 hours of drug treatment, and their migration was observed under an inverted microscope. The pictures were processed with Image J software to analyze the ability of cell migration.

Colony formation assays

The cells (AGS and SGC-7901) were fixed with 10% formalin and subjected to crystal violet staining for 30 minutes after 48 hours of transfection with ARID1A cDNA, or pcDNA3.1. Next, the staining solution was carefully discarded, and each well was thoroughly rinsed with water. The plate was then dried by turning it over on absorbent paper. Finally, cell colony formation was observed. The results are expressed as the average cell numbers in each field of view.

Flow cytometry

To assess apoptosis in the AGS and SGC-7901 cells, an annexin V-FITC apoptosis assay kit (KeyGEN Biotech, Jiangsu, China) was used after the transfection of the ARID1A cDNA plasmid. The flow cytometry analysis was performed using a BD FACSVerse flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test for comparison of two groups or one-way analysis of variance for comparison of more than two groups. The statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS 13.0 Statistical Computer Program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and the results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation based on three independent assessments. A difference was considered significant when the P value from a two-tailed test was <0.05.

Results

The effects of overexpression and knockdown of ARID1A

PcDNA3.1 was used as the vector, and the plasmid was extracted after transformation and shaking, and transfected into AGS and SGC-7901 cells, respectively. The level of expression of ARID1A in the cells (AGS and SGC-7901) was detected by Western blot. The cells transfected with the ARID1A cDNA plasmid had significantly higher levels of ARID1A protein than those transfected with pcDNA3.1. The pcDNA 3.1 and control blank groups did not exhibit significant differences (Figure 1A). Following the knockdown of ARID1A, the opposite result was found (Figure 1B).

Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted to assess the level of ARID1A messenger RNA (mRNA) expression. The results showed that the level of ARID1A mRNA was significantly higher in the ARID1A group than the pcDNA3.1 group and control blank group (P<0.001). However, no differences in the ARID1A mRNA levels were observed between the pcDNA3.1 group and the control group (Figure 1C).

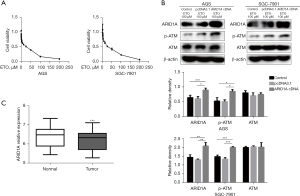

ETO induced DSBR in GC cells

To explore whether ETO induced apoptosis, we examined the effects of ETO in human gastric adenocarcinoma cells. AGS and SGC-7901 cells were treated with ETO at different concentrations for 24 hours to observe the effect of ETO on cell survival rate. The MTT experiments revealed that ETO had a dose-dependent effect (i.e., the higher ETO concentration, the greater the inhibition of GC cell growth). The observed half-maximal inhibitory concentration value was 14.81 µM in the AGS cells and 23.81 µM in the SGC-7901 cells (Figure 2A).

We transfected ARID1A cDNA into AGS and SGC-7901 cells. The AGS and SGC-7901 cells were treated for 24 hours with 100 µM of ETO. The change level of each protein mass in each group was detected by Western blot. Wang et al. found that DNA double-strand breaks repair is orchestrated by the p-ATM (11). We also examined the ATM levels of each group due to the differences in ARID1A expression and studied ARID1A’s mode of action in DSBR. The results revealed no change in the total ATM levels and a significant increase in p-ATM following ARID1A transfection, which suggests that ARID1A may be involved in DSBR (Figure 2B). The gene expression data of the sample GSE29272 data set showed a lower level of ARID1A in GC tissues (6.149±0.488) than normal stomach tissue (6.359±0). The difference was statistically significant at 485 (P<0.001) (Figure 2C). The results were consistent with our previous findings, which suggested an association between ARID1A and GC (11).

ARID1A involvement in DSBR

We used ETO to establish a DSB model to evaluate DNA damage in both cells (SGC-7901 and AGS) and to examine whether ARID1A has a direct effect on DNA DSBR. Under an electrophoretic field, damaged cellular DNA (containing fragments and strand breaks) is separated from intact DNA, yielding a classic “comet tail” shape under the microscope. After the 100 mM ETO treatment, there was a significant increase in DNA damage, and the cells showed a greater tail DNA percentage. The results indicated that ETO induced DNA damage in the treated cells, while DNA damage was considerably reduced following the overexpression of ARID1A, and vice versa (Figure 3A).

This study simultaneously detected DNA DSBR using neutral comet electrophoresis and immunocytochemistry. Besides its involvement in chromatin remodeling, γ-H2AX has also been associated with several cellular functions, such as DNA repair (12). In response to a DSB, γH2AX occur to initiate repair, rapidly and meticulously. This promotes the recruitment of downstream DSB repair molecules, in addition to ensuring genomic stability (13). The location of labeled ARID1A and γ-H2AX was detected using the immunofluorescence technique to determine whether ARID1A was recruited to the DNA break site in the early stage of the DSBR. Under the influence of ETO, the expression of γ-H2AX and ARID1A increased significantly, ARID1A and γ-H2AX co-localized, which suggests that ARID1A plays a potential role in DSBR (Figure 3B).

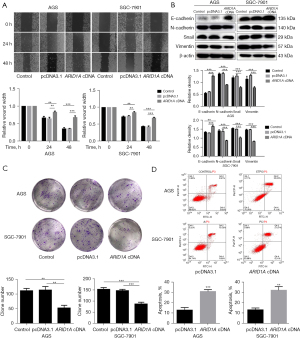

ARID1A as a suppressor gene of tumor cells

The overexpression of ARID1A slowed the rate of wound healing, while the knock down of ARID1A accelerated the rate of wound healing (Figure 4A). This indicates that the migration of GC cells is negatively correlated with ARID1A. The overexpression of ARID1A resulted in higher epithelial marker levels and lower mesenchymal marker levels, while the knock down of ARID1A had the exact opposite effects (Figure 4B).

Colony formation tests were used to detect the effects of ARID1A transfection on the SGC-7901 and AGS cells over a long period. The results showed that the cloning ability of the cells was reduced after the overexpression of ARID1A (Figure 4C).

Flow cytometry was performed to examine the cell apoptosis of the AGS and SGC-7901 cells, and its relationship with ARID1A. Compared to the control group, the transfection of ARID1A induced the apoptosis in both groups of treated cells (Figure 4D), which suggests that ARID1A may also exert anti-cancer effects by promoting the apoptosis of cells associated with cancer.

Discussion

GC is a commonly occurring cancer (14). However, due to differences among patients, the epigenetic inheritance of genes is extremely complex, and there are no unambiguous predictors of treatment efficacy or prognostic indicators. As some DNA repair-related molecules in cancer cells undergo structural or functional changes, an approach that enabled the targeted delivery of therapeutic drugs based on these molecules would be valuable in tumor therapy. ETO is a cell cycle-specific antitumor drug that causes DSBs by forming a complex of topoisomerase II-DNA (15). Topoisomerase II catalyzes the topological transition of DNA duplex, thereby affecting transcription DNA replication, chromosome condensation, and separation of sister chromatids during mitosis produce transient double strand breaks in the DNA double helix. ETO interferes with the ability of topoisomerase II to reconnect nicks in DNA strands, causing DNA double strand breaks. The accumulation of DNA fragmentation increases and induces tumor cell apoptosis (16). Wiegand et al. (17) reported a 14% deletion rate of ARID1A in GC. The abnormal expression and mutation of the ARID1A gene has been reported in endometrioid and uterine clear cell carcinoma (18), cervical cancer (19), bladder cancer (20), lung cancer (21), and kidney cancer (22). A loss of ARID1A expression has also been shown to be related to a poor prognosis in GC patients (P=0.003) (9). A study detected the expression of mismatch repair protein and ARID1A protein in 489 cases of primary gastric adenocarcinoma by immunohistochemistry. The results showed that the inactivation of aird1a protein was associated with lymphatic invasion, lymph node metastasis, poor prognosis and lack of repair protein in gastric adenocarcinoma (23). From the analysis of these tissue samples, we can see that ARID1A has a close relationship with DNA damage repair, but the mechanism by which ARID1A regulates the repair process needs further study.

In the known kinase stress network, ATM kinase is thought to be the initiator of cellular responses after DNA damage. ATM is the main initiator of the signaling cascade in response to double strand breaks, and after DNA damage, ATM undergoes autophosphorylation, leading to the separation of inactive complexes and the formation of highly active monomers. Subsequently, DNA repair can be carried out through the activation of signaling pathways and the phosphorylation of many substrates, during which the activation of cell cycle checkpoints and the initiation of DNA repair are promoted (24). In our study, ARID1A was overexpressed in two cell lines and the phosphorylation level of protein ATM was found to be increased, suggesting that the DNA damage repair involved by ARID1A may be mediated by ATM, but how ARID1A affects the phosphorylation of ATM is not known. Our study showed that ARID1A was involved in DNA damage repair. The DNA damage response system, which involves γ-H2AX, is crucial in preserving genomic integrity by signaling and facilitating the repair of DNA double-strand breaks (25,26). When the DNA of a cell undergoes DSB, the signaling and detection of the damaged site stimulate the formation of γ-H2AX, which exerts a vital effect in response to DNA damage and also involves DNA repair (27). The results of this study showed that with the effect of ETO, the expression of γ-H2AX and ARID1A was significantly increased. The co-localization of ARID1A and γ-H2AX further confirmed that ARID1A may participate in DNA damage repair.

Our study found that ARID1A may participate in DNA damage repair. As a tumor suppressor gene, it seems that its function does not match. We speculate that ARID1A, as an anticancer molecule, will inhibit cell proliferation and migration, weaken wound healing ability, and even induce apoptosis when tumor cells are not internally damaged by DNA. ARID1A, as the core subunit of chromatin remodeling complex, participates in the repair of DNA damage when it is in danger of DNA double strand break, but the reason for this difference needs to be further explored.

Conclusions

ARID1A may participate in the DNA double strand break repair of gastric adenocarcinoma cell line caused by ETO through the p-ATM pathway. ARID1A can inhibit the migration and proliferation of gastric adenocarcinoma cell lines and promote apoptosis.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the MDAR reporting checklist. Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-283/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-283/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-283/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-283/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Zhang FL, Li DQ. Targeting Chromatin-Remodeling Factors in Cancer Cells: Promising Molecules in Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:12815. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Church MC, Price A, Li H, et al. The Swi-Snf chromatin remodeling complex mediates gene repression through metabolic control. Nucleic Acids Res 2023;51:10278-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Wu D, Lu Wang, et al. Research progress of tumor suppressor gene ARID1A. Journal of Shenyang Medical College 2019;21:69-74.

- Ahmad K, Brahma S, Henikoff S. Epigenetic pioneering by SWI/SNF family remodelers. Mol Cell 2024;84:194-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu S, Jordán-Pla A, Gañez-Zapater A, et al. SWI/SNF interacts with cleavage and polyadenylation factors and facilitates pre-mRNA 3' end processing. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46:8557-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Sun Q, Shan M, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of ARID1A gene is responsible for its low mRNA expression in many invasive breast cancers. PLoS One 2013;8:e53931. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim S, Zhang Z, Upchurch S, et al. Structure and DNA-binding sites of the SWI1 AT-rich interaction domain (ARID) suggest determinants for sequence-specific DNA recognition. J Biol Chem 2004;279:16670-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu JN, Roberts CW. ARID1A mutations in cancer: another epigenetic tumor suppressor? Cancer Discov 2013;3:35-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu YP, Sheng LL, Wu J, et al. Loss of ARID1A expression is associated with poor prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. Hum Pathol 2018;78:28-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakr A, Corte GD, Veselinov O, et al. ARID1A regulates DNA repair through chromatin organization and its deficiency triggers DNA damage-mediated anti-tumor immune response. Nucleic Acids Res 2024;52:5698-719. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Z, Gong Y, Peng B, et al. MRE11 UFMylation promotes ATM activation. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47:4124-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kirkiz E, Meers O, Grebien F, et al. Histone Variants and Their Chaperones in Hematological Malignancies. Hemasphere 2023;7:e927. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Atkinson J, Bezak E, Le H, et al. DNA Double Strand Break and Response Fluorescent Assays: Choices and Interpretation. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25:2227. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xia C, Dong X, Li H, et al. Cancer statistics in China and United States, 2022: profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin Med J (Engl) 2022;135:584-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang W, Gou P, Dupret JM, et al. Etoposide, an anticancer drug involved in therapy-related secondary leukemia: Enzymes at play. Transl Oncol 2021;14:101169. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marinello J, Delcuratolo M, Capranico G. Anthracyclines as Topoisomerase II Poisons: From Early Studies to New Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:3480. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wiegand KC, Lee AF, Al-Agha OM, et al. Loss of BAF250a (ARID1A) is frequent in high-grade endometrial carcinomas. J Pathol 2011;224:328-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kandoth C, Schultz N, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013;497:67-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Helming KC, Wang X, Wilson BG, et al. ARID1B is a specific vulnerability in ARID1A-mutant cancers. Nat Med 2014;20:251-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faraj SF, Chaux A, Gonzalez-Roibon N, et al. ARID1A immunohistochemistry improves outcome prediction in invasive urothelial carcinoma of urinary bladder. Hum Pathol 2014;45:2233-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Xu X, Zhang M, et al. ARID1A is downregulated in non-small cell lung cancer and regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis. Tumour Biol 2014;35:5701-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park JH, Lee C, Suh JH, et al. Decreased ARID1A expression correlates with poor prognosis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol 2015;46:454-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inada R, Sekine S, Taniguchi H, et al. ARID1A expression in gastric adenocarcinoma: clinicopathological significance and correlation with DNA mismatch repair status. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:2159-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caputo F, Vegliante R, Ghibelli L. Redox modulation of the DNA damage response. Biochem Pharmacol 2012;84:1292-306. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trakarnphornsombat W, Kimura H. Live-cell tracking of γ-H2AX kinetics reveals the distinct modes of ATM and DNA-PK in the immediate response to DNA damage. J Cell Sci 2023;136:jcs260698. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prabhu KS, Kuttikrishnan S, Ahmad N, et al. H2AX: A key player in DNA damage response and a promising target for cancer therapy. Biomed Pharmacother 2024;175:116663. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yachi Y, Matsuya Y, Yoshii Y, et al. An Analytical Method for Quantifying the Yields of DNA Double-Strand Breaks Coupled with Strand Breaks by γ-H2AX Focus Formation Assay Based on Track-Structure Simulation. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:1386. [Crossref] [PubMed]