Prognostic nomogram for overall survival of elderly esophageal cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy: a population-based analysis

Highlight box

Key findings

• We constructed a novel nomogram model for elderly esophageal cancer patients with neoadjuvant therapy.

What is known and what is new?

• Elderly patients had higher short-term mortality and poorer long-term survival.

• There was no statistical difference in overall survival (OS) between neoadjuvant chemotherapy or neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for elderly patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma or esophageal adenocarcinoma.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• T stage, N stage, M stage, and sex were independent OS prognostic factors. A nomogram, better than the tumor-node-metastasis staging system, was created. Patients were stratified into high-, medium-, and low-risk groups, with statistical differences in long-term survival. High- and medium-risk patients should have more frequent follow-ups and adjuvant therapy if needed.

Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) is one of the most common and challenging cancer types, with 572,000 newly diagnosed cases and 500,000 deaths annually (1). In recent decades, with the aging of the global population (2,3) and the increase in life expectancy, the number of elderly patients with EC has gradually increased. Currently, EC occurs mainly in middle-aged and elderly people. The average age of EC diagnosis is 67 years, and about 30% of patients are over 75 years old (4,5). Further, elderly EC patients often have degenerative diseases that do not tolerate surgery well and have a high risk of side effects after radiation or chemotherapy.

Neoadjuvant therapy (chemoradiotherapy in Western countries, and chemotherapy in Asia, especially in Japan) plus esophagectomy is still the first-line recommendation for patients with locally advanced EC. As the population of elderly patients with EC increases, it becomes more critical to understand the prognostic factors especially in relation to the mortality and morbidity of an esophagectomy in this challenging population. Up to now, population-based evidence on the prognostic factors in elderly patients with EC receiving neoadjuvant therapy and esophagectomy is limited.

In this study, we aimed to identify the prognostic factors and type of neoadjuvant therapy among elderly EC patients. Further, we aimed to develop a nomogram for feasible individualized follow-up plans and to assist in clinical decision making. We present this article in accordance with the TRIPOD reporting checklist (6) (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-392/rc).

Methods

Study design and patient selection

Data used in this study were extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. This study included patients diagnosed with EC who received neoadjuvant therapy plus surgery from 2004 to 2015 in the SEER database. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) diagnosis of primary EC; (II) receiving neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT) and neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone (nCT); (III) complete clinicopathological features, demographic data, and follow-up data; (IV) aged above 60 years. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Variable definitions

Included variables were patients’ demographic characteristics (age, sex, race, insurance status, and marital status), disease characteristics (histology, primary site, tumor size, grade, T, N, and M stages), and neoadjuvant therapy, time to survival, and life status. We used X-tile software (Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA) to determine the optimal cutoff value in age and tumor size for overall survival (OS). Neoadjuvant treatment was classified into nCRT and nCT. Under the condition of systemic therapy before surgery or systemic therapy before and after surgery, patients receiving neoadjuvant radiotherapy were included in the selection process, noted as nCRT. The cutoff value was 68 years for age and between 24 and 59 mm for tumor size. The primary site included a lower third of the esophagus, middle third of the esophagus, and upper third of esophagus. The histological types included adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and others. Tumor differentiation included grades I, II, III, and IV. All cases included for further analysis were staged by the 7th tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system.

Statistical analysis

OS was the primary endpoint of the study. First, we randomly divided the patients into the training and validation cohorts in a 7:3 ratio. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional risk regression analyses of the training cohort was conducted to identify independent prognostic factors. Then, a nomogram model was constructed to predict patients’ OS from the identified independent risk factors. We used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and the area under the curve (AUC) to evaluate the discriminant ability of the nomogram model. Calibration curves were used to measure the agreement between predicted and actual results and decision curve analysis (DCA) to evaluate the clinical value of the rosette. X-tile was used to quickly determine the cutoff values for survival data. The principle of X-tile to find the best cutoff values was the “enumeration method”. Different values were grouped as truncation values for the statistical test, and the result with the smallest P value was considered the best cutoff value. We used X-tile software to determine the optimal cutoff value of risk score and divided the patients into 3 groups: low, medium, and high risk. We compared the predictive efficacy of the 7th TNM system with the nomogram model using the integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) method (7). To verify the accuracy and performance of the established model, we further evaluated the predictive power, heterogeneity of predicted results and actual results, and clinical application value in the validation cohort. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R software (version 3.6.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A P value <0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics in both the training cohort and validation group

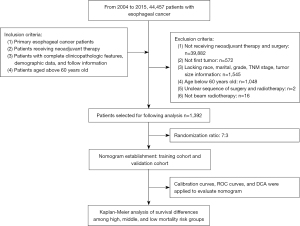

The process of patient screening and data analysis in this study is shown in Figure 1. From 2004 to 2015, a total of 44,457 patients with EC were included in the SEER database, of which a total of 1,392 patients were screened for further analysis. The patient selection details are summarized in Figure 1. Among 1,392 patients who received neoadjuvant therapy, 149 received nCT, and 1,243 received nCRT. We randomly divided 1,392 patients into the training cohort (n=976) and validation cohort (n=416) in a 7:3 ratio. The baseline characteristics in the training cohort and the validation group are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Training cohort (n=976), n (%) | Validation cohort (n=416), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| 61–68 | 595 (61.0) | 250 (60.1) |

| >68 | 381 (39.0) | 166 (39.9) |

| Sex | ||

| Women | 149 (15.3) | 62 (14.9) |

| Men | 827 (84.7) | 354 (85.1) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 727 (74.5) | 304 (73.1) |

| Unmarried | 249 (25.5) | 112 (26.9) |

| Race | ||

| Black | 34 (3.5) | 15 (3.6) |

| White | 911 (93.3) | 380 (91.4) |

| Other | 31 (3.2) | 21 (5.0) |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 701 (71.8) | 288 (69.2) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 163 (16.7) | 75 (18.0) |

| Other | 112 (11.5) | 53 (12.7) |

| T stage | ||

| T1–2 | 262 (26.8) | 122 (29.3) |

| T3–4 | 714 (73.2) | 294 (70.7) |

| N stage | ||

| N0 | 353 (36.2) | 148 (35.6) |

| N1 | 623 (63.8) | 268 (64.4) |

| M stage | ||

| M0 | 892 (91.4) | 380 (91.4) |

| M1 | 84 (8.6) | 36 (8.6) |

| Grade | ||

| Grade I | 41 (4.2) | 17 (4.1) |

| Grade II | 399 (40.9) | 167 (40.1) |

| Grade III | 525 (53.8) | 228 (54.8) |

| Grade IV | 11 (1.1) | 4 (1.0) |

| Primary site | ||

| Lower | 790 (80.9) | 334 (80.3) |

| Middle | 96 (9.8) | 46 (11.1) |

| Upper | 8 (0.8) | 5 (1.2) |

| Other | 82 (8.4) | 31 (7.5) |

| Tumor size | ||

| <24 mm | 171 (17.5) | 67 (16.1) |

| 24–59 mm | 497 (50.9) | 223 (53.6) |

| >59 mm | 308 (31.6) | 126 (30.3) |

| Neoadjuvant type | ||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 109 (11.2) | 40 (9.6) |

| Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy | 867 (88.8) | 376 (90.4) |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | ||

| No | 922 (94.5) | 392 (94.2) |

| Yes | 54 (5.5) | 24 (5.8) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||

| No | 883 (90.5) | 382 (91.8) |

| Yes | 93 (9.5) | 34 (8.2) |

Univariate Cox analysis and multivariate Cox analysis

The results of univariate and multivariate Cox analysis in the training cohort are summarized in Table 2. Univariate Cox analysis indicated that T stage, M stage, N stage, pathological grade, gender, and tumor size were significantly correlated with OS (P<0.05). However, multivariate Cox analysis indicated that grade and tumor size were not statistically significant. Cox multivariate results indicated that T stage, M stage, N stage, and gender were independent prognostic factors of OS (P<0.05).

Table 2

| Characteristics | Univariate Cox analysis | Multivariate Cox analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Age, years | |||||

| 61–68 | 1.00 | ||||

| >68 | 1.09 (0.93–1.27) | 0.28 | |||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |||||

| No | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 0.95 (0.73–1.22) | 0.68 | |||

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | |||||

| No | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 0.98(0.72–1.38) | 0.98 | |||

| Grade | |||||

| Grade I | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Grade II | 1.25 (0.82–1.92) | 0.30 | 1.19 (0.78–1.83) | 0.42 | |

| Grade III | 1.63 (1.07–2.49) | 0.02 | 1.49 (0.98–2.27) | 0.07 | |

| Grade IV | 1.28 (0.52–3.14) | 0.59 | 1.29 (0.52–3.17) | 0.58 | |

| Histology | |||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1.00 | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 0.85 (0.68–1.05) | 0.12 | |||

| Other | 0.99 (0.78–1.26) | 0.13 | |||

| M stage | |||||

| M0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| M1 | 1.54 (1.20–1.99) | 0.001 | 1.47 (1.13–1.9) | 0.004 | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 1.00 | ||||

| Unmarried | 1.09 (0.92–1.30) | 0.31 | |||

| N stage | |||||

| N0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| N1+ | 1.67 (1.42–1.98) | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.32–1.85) | <0.001 | |

| Primary site | |||||

| Upper | 1.00 | ||||

| Middle | 0.94 (0.38–2.33) | 0.89 | |||

| Lower | 1.21 (0.50–2.92) | 0.67 | |||

| Other | 1.51 (0.61–3.76) | 0.37 | |||

| Race | |||||

| Black | 1.00 | ||||

| White | 1.33 (0.86–2.05) | 0.37 | |||

| Other | 0.9 (0.46–1.74) | 0.75 | |||

| Neoadjuvant type | |||||

| Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy | 1.00 | ||||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 1.01 (0.80–1.28) | 0.92 | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Male | 1.33 (1.06–1.66) | 0.0013 | 1.3 (1.04–1.62) | 0.023 | |

| T stage | |||||

| T1–2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| T3–4 | 1.47 (1.22–1.76) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.04–1.53) | 0.016 | |

| Tumor size | |||||

| <24 mm | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 24–59 mm | 1.24 (1–1.55) | 0.05 | 1.08 (0.86–1.35) | 0.51 | |

| >59 mm | 1.36 (1.08–1.72) | 0.01 | 1.06 (0.83–1.36) | 0.62 | |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

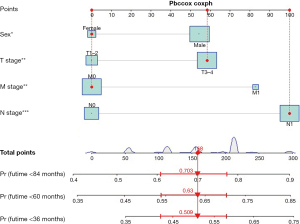

Development and validation of a nomogram model

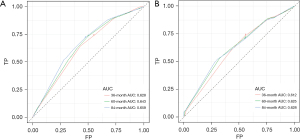

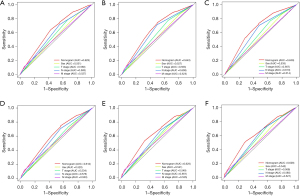

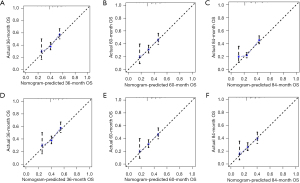

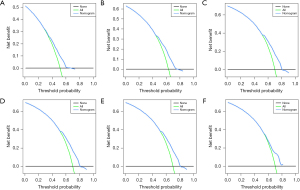

Based on independent prognostic factors, we constructed a nomogram to predict OS for EC patients at 36, 60, and 84 months (Figure 2). Time-dependent ROC curves showed that the nomogram could effectively predict OS, and the prediction power of the model was promising (Figure 3). The AUC was 0.628, 0.643, and 0.659 at 36, 60, and 84 months, respectively, in the training cohort. The AUC was 0.612, 0.625, and 0.628 at 36, 60, and 84 months, respectively, in the validation cohort. At the same time, the nomogram had a higher prediction accuracy than each single independent prognostic factor included in the model (Figure 4). The nomogram correction curve showed a high degree of agreement between the predicted and actual results in the training and validation queues (Figure 5). DCA confirmed that the established model had strong clinical applicability not only in the training cohort but also in the validation cohort (Figure 6).

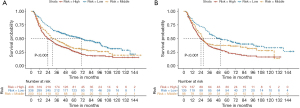

Risk stratification and Kaplan-Meier analysis

We divided the participants into a low death risk subgroup, a medium death risk subgroup, and a high death risk subgroup according to the nomogram score by X-tile software. Patients in the low-risk subgroups had scores below 5, whereas the high-risk subgroups had a score of 10. The medium death risk subgroup had score ranging from 5 to 10 (Figure 7). Subgroup analysis of elderly EC patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy indicated that when the patients were classified as low risk, they tended to have a better long-term prognosis, with P values of <0.001 and <0.001 in the validation cohort and training cohort, respectively.

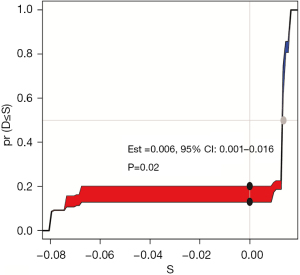

Comparison with TNM staging system

IDI to compare the predictive ability of nomogram model and TNM stage system. Compared to TNM system, IDI >0 indicated that established model had better predictive value. We used IDI to compare the predictive ability of 60-month OS between the nomogram model and the TNM stage system. The IDI value was 0.006 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.001–0.016, P=0.02], indicating good predictive power of the established model (Figure 8).

Discussion

A previous study indicated that EC survival improved gradually and consistently in American adults from 1973 to 2009 (8). The reasons behind this were not only early detection of EC but also the benefit of neoadjuvant therapy and improved surgical techniques. However, a study suggested that elderly patients had higher short-term mortality rate and poorer long-term survival (9). Thus, how to deal with elderly EC patients has remained a challenge for thoracic surgeons. To our knowledge, this was the first study focusing on the factors affecting the long-term survival of elderly EC receiving neoadjuvant treatment (including nCRT and nCT) plus surgery based on a population analysis. We found that T stage, M stage, N stage, and sex were independent prognostic factors of OS. A reliable prognostic nomogram with better predictive ability than the TNM stage system was established. Further, we also stratified patients into 3 categories (high-, medium-, and low-risk groups) according to different clinical and pathological manifestations, which showed statistical differences in the long-term survival in both training and validation cohorts. Based on this model, patients in high- or medium-risk groups should have a more active and frequent follow-up and receive adjuvant therapy if necessary.

The pathological grade was used as an independent prognostic factor in previous reports (10,11). A study showed that poorly differentiated EC indicated a worse prognosis due to the higher rate of lymph node metastasis and distant organ metastasis rate (12), and a significant relationship between liver metastasis rate and pathological grade was detected. The pathological grade could guide adjuvant therapy after surgery (13), as patients with poorly differentiated tumors respond better to nCRT than those with well- or moderately-differentiated tumors (14). However, we found that pathological grade was not a risk factor in elderly EC patients. This finding was consistent with the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), which excluded pathological grade diagnosis after neoadjuvant treatment as a stage factor.

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is still the most common subtype of EC in the Asian population. In recent years, esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) has been the major subtype in Western countries and one of the fastest growing cancers (15). The pathological type in this study did not suggest statistical significance in OS, which was consistent with AJCC 8th. The TNM stage is the most popular tool for the prediction of long-term prognosis. For patients with lymph node metastasis, although a systematic lymph node dissection had been performed, many of them were performed in only 2 or 2.5 fields of lymph node dissection due to the limitation of the patients’ own conditions (lung function and advanced heart function) or the complicated anatomical position. Due to the inability to completely clear the cancer cells, potential metastasis or micro metastasis of the lymph nodes may occur, which has a great impact on the patient’s prognosis (16-18). Additionally, if radical esophagectomy is not performed, patients are more likely to develop distant metastases.

We found that sex was another prognostic factor. Compared with men with EC, women with EC had a better prognosis. Kauppila et al. found that compared with men, all-cause death was reduced in women with ESCC [hazard ratio (HR) =0.73, 95% CI: 0.63–0.85]. Stratified analysis showed that mortality was reduced in women over 55 years of age (HR =0.71, 95% CI: 0.61–0.83), especially stage 0–I (HR =0.54, 95% CI: 0.37–0.79). There was no difference in the mortality results of EAC regarding to sex (11). Bohanes et al. also found that in comparison with men, women (aged 55 years old) with locally advanced EC had a significantly better outcome (12). The possible mechanisms of the long-term prognosis difference between men and women were reported: estrogen receptors (ERs) were expressed in ESCC, and estrogens could inhibit squamous cell tumor growth (14,19); carcinogenic human papilloma virus (HPV) played an important role in the pathogenesis of ESCC in high-risk areas (20,21).

The location of EC was also a prognostic factor in the previous report. However, in this study, there was not a significant difference, which was consistent with previous report (22). Compared with the earlier surgical method, it was difficult for the upper third thoracic EC to achieve completely radical resection of lymph nodes. Further, the intraoperative and postoperative risk (intraoperative bleeding or anastomotic leak) was higher than those in the middle or lower third. With the development of neoadjuvant therapy, now, downstaging could be achieved through neoadjuvant treatment, making it more possible to achieve a suitable state for esophagectomy. Further, with the development of minimally invasive techniques, especially the method of laryngeal recurrent nerve lymph nodes dissection, the safety, and efficacy of esophagectomy in upper thoracic EC has also gained remarkable progress.

A previous study has concluded that nCRT was not superior to nCT in the long-term for patients with EAC (22). Based on our analysis, there was no statistical difference in OS between nCT and nCRT for the elderly patients with ESCC or EAC, which suggested that nCT and nCRT were both acceptable for elderly ESCC. This finding was in contrast to the previous report on ESCC, which concluded that nCRT seems to remain the optimal treatment approach for ESCC (23). Previous studies have indicated that radiotherapy could cause more potential treatment-related complications, such as acute toxic reactions, radiation esophagitis, radiation pneumonia, and pericardial effusion (24-28), and the above complications may cause significant decreases in patient quality of life. Considering the treatment-related adverse events and difficulty in quality control of radiotherapy, it and maybe a better choice for elderly ESCC in both EAC and ESCC.

To our knowledge, research on the characteristics and treatment of elderly EC patients is relatively limited. In this study, we established a reliable nomogram and risk-stratification system to predict the OS of elderly EC patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy. Compared to the TNM system, the present model had better predictive ability based on the IDI analysis (IDI =0.006, P=0.02). There are a multitude of other tools that exist. Gabriel et al. established a tool included Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score, tumor grade, clinical T and N status, and nCRT before surgery to predict OS of patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma (AUC =0.630 for 1-year OS, and AUC =0.682 for 3-year OS) (29). Lemini et al. evaluated existing models and performed external validation of selected model to predict the OS of EC and found that the existing model require implementation in clinical practice to optimize their clinical utility (30). Considering the elderly patients had poorer outcomes, we developed a special model to predict patients receiving nCT or nCRT for elderly EC. Considering the insufficient variables in SEER database, the AUC value of this model was moderate, and should be further refined.

However, our study had several limitations. First, most of the patients included in the SEER database were Caucasian, and most of the pathological types were EAC, which limits the application of this model in the Asian population with ESCC. Second, this model was only verified internally. There was no external validation to further confirm this model. Third, we were unable to extract information about the general conditions and complications of elderly patients from the SEER database, which may affect the treatment choice of patients, and perioperative complications were associated with long-term prognosis, which both caused potential bias. Fourth, there was insufficient information about why patients received nCT rather than nCRT. Fifth, there were no details on the type of chemotherapy used or the radiation dose delivered. Sixth, there might survivor bias, which caused by the difference of tolerance of neoadjuvant therapy.

Conclusions

In this study, we constructed a novel nomogram model for elderly EC patients. This nomogram can predict the OS for elderly EC patients, enabling timely follow-up and postoperative treatment.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The study was supported by

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the TRIPOD reporting checklist. Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-392/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-392/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-392/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Lu L, Mullins CS, Schafmayer C, et al. A global assessment of recent trends in gastrointestinal cancer and lifestyle-associated risk factors. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2021;41:1137-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Global, regional, and national mortality among young people aged 10-24 years, 1950-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2021;398:1593-618. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Partridge L, Deelen J, Slagboom PE. Facing up to the global challenges of ageing. Nature 2018;561:45-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faiz Z, Lemmens VE, Siersema PD, et al. Increased resection rates and survival among patients aged 75 years and older with esophageal cancer: a Dutch nationwide population-based study. World J Surg 2012;36:2872-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Islami F, DeSantis CE, Jemal A. Incidence Trends of Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Subtypes by Race, Ethnicity, and Age in the United States, 1997-2014. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:429-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moons KG, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, et al. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:W1-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Smeden M, Moons KGM. Event rate net reclassification index and the integrated discrimination improvement for studying incremental value of risk markers. Stat Med 2017;36:4495-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Njei B, McCarty TR, Birk JW. Trends in esophageal cancer survival in United States adults from 1973 to 2009: A SEER database analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;31:1141-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lagergren J, Bottai M, Santoni G. Patient Age and Survival After Surgery for Esophageal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2021;28:159-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agrawal N, Jiao Y, Bettegowda C, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of esophageal adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Discov 2012;2:899-905. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kauppila JH, Wahlin K, Lagergren P, et al. Sex differences in the prognosis after surgery for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer 2019;144:1284-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bohanes P, Yang D, Chhibar RS, et al. Influence of sex on the survival of patients with esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2265-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li X, Tian D, Guo Y, et al. Genomic characterization of a newly established esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell line from China and published esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Cell Int 2020;20:184. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang C, Wang P, Liu JC, et al. Interaction of Estradiol and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in the Development of Esophageal Carcinoma. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020;11:410. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajendra K, Sharma P. Viral Pathogens in Oesophageal and Gastric Cancer. Pathogens 2022;11:476. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shang QX, Yang YS, Xu LY, et al. Prognostic impact of lymph node harvest for patients with node-negative esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a large-scale multicenter study. J Gastrointest Oncol 2021;12:1951-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xia W, Liu S, Mao Q, et al. Effect of lymph node examined count on accurate staging and survival of resected esophageal cancer. Thorac Cancer 2019;10:1149-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang Z, Hong Z, Chen L, et al. Nomogram for Predicting Occult Locally Advanced Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Before Surgery. Front Surg 2022;9:917070. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu Z, Zhang Y, Lagergren J, et al. Circulating Sex Hormone Levels and Risk of Gastrointestinal Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2023;32:936-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Syrjänen KJ. HPV infections and oesophageal cancer. J Clin Pathol 2002;55:721-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tribius S, Ihloff AS, Rieckmann T, et al. Impact of HPV status on treatment of squamous cell cancer of the oropharynx: what we know and what we need to know. Cancer Lett 2011;304:71-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang H, Fang W, Lin Y, et al. Predictive Model for Overall Survival and Cancer-Specific Survival in Patients with Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. J Oncol 2021;2021:4138575. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamarajah SK, Phillips AW, Ferri L, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy alone for oesophageal cancer: population-based cohort study. Br J Surg 2021;108:403-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu Y, Zheng H, Liu L, et al. Predicting Severe Radiation Esophagitis in Patients With Locally Advanced Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Receiving Definitive Chemoradiotherapy: Construction and Validation of a Model Based in the Clinical and Dosimetric Parameters as Well as Inflammatory Indexes. Front Oncol 2021;11:687035. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang W, Li X, Yu H, et al. A novel nomogram containing acute radiation esophagitis predicting radiation pneumonitis in thoracic cancer receiving radiotherapy. BMC Cancer 2021;21:585. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Imano N, Nishibuchi I, Kawabata E, et al. Evaluating Individual Radiosensitivity for the Prediction of Acute Toxicities of Chemoradiotherapy in Esophageal Cancer Patients. Radiat Res 2021;195:244-52. [PubMed]

- Pao TH, Chang WL, Chiang NJ, et al. Pericardial effusion after definitive concurrent chemotherapy and intensity modulated radiotherapy for esophageal cancer. Radiat Oncol 2020;15:48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hong ZN, Gao L, Weng K, et al. Safety and Feasibility of Esophagectomy Following Combined Immunotherapy and Chemotherapy for Locally Advanced Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Front Immunol 2022;13:836338. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gabriel E, Attwood K, Shah R, et al. Novel Calculator to Estimate Overall Survival Benefit from Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation in Patients with Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 2017;224:884-894.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lemini R, Díaz Vico T, Trumbull DA, et al. Prognostic models for stage I-III esophageal cancer: a comparison between existing calculators. J Gastrointest Oncol 2021;12:1963-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]