A case of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma implantation in multiple branches of the pancreatic duct without main tumor continuity: a rare case report

Highlight box

Key findings

• Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma (PACC) can disseminate and get implanted in multiple branches of the pancreatic duct (BDs) without any continuity with the main tumor.

What is known and what is new?

• Up to 10% of PACCs invade the main pancreatic duct (MPD) and grow along it.

• We found that the tumor that had invaded the MPD had peeled off, disseminated, and gotten implanted in multiple BDs.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• PACC can relapse in the liver, lymph nodes, peritoneum, and lung. The findings of our case and those previously reported indicate that PACC could metastasize via the bile duct, MPD, and portal vein, resulting in intraductal growth. Furthermore, the tumor can get implanted in the common bile duct and BDs. Thus, we should monitor for relapse in the remnant pancreas in addition to the usual sites.

Introduction

Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma (PACC) is a rare subtype of pancreatic cancer, accounting for 1–2% of all exocrine pancreatic neoplasms (1). Because of its rarity, the clinicopathological behavior of PACC is not yet fully understood. Local invasion of the surrounding organs, including the duodenum, stomach, kidney, peritoneum and spleen, is observed in approximately 45% of all PACC cases (2). Moreover, approximately 10% of patients with PACC have pancreatic ductal ingrowth (3-8). Herein, we have presented a case of PACC, in which the tumor had invaded the main pancreatic duct (MPD) and had disseminated to multiple downstream branches of the pancreatic duct (BDs) without demonstrating any continuity with the main tumor. Because no similar case has been previously reported, we aimed to discuss our experience with the patient in this case report. We present this case in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-511/rc).

Case presentation

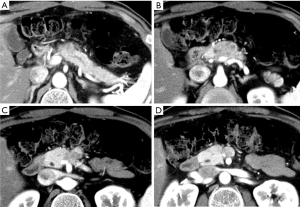

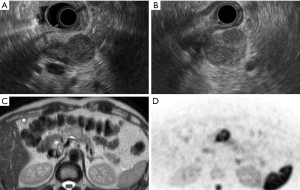

A 60-year-old man was found to have a pancreatic tumor on an abdominal ultrasound that was performed during a routine medical checkup. Thus, an abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed. It revealed a 30-mm hypo-dense mass (Figure 1A-1D) in the pancreas (head and body), which prompted further examination. The patient had a history of hyperlipidemia and hyperuricemia. He drank alcohol four times per week (500 mL of beer each time). He used to smoke 2–3 cigarettes per day. His uncle and aunt had a history of a malignant tumor. At the time of admission, his height, weight, and body temperature were 168 cm, 64 kg, and 36.4 ℃, respectively. His abdomen was soft and flat with no palpable mass. Blood investigations yielded the following results: amylase, 77 IU/L; lipase, 53 IU/L; and carbohydrate antigen 19-9, 41 IU/L. Endoscopic ultrasonography revealed a round-to-oval 30-mm well-circumscribed hypo-echoic lesion in the pancreas (Figure 2A,2B). Magnetic resonance image also showed relatively high intensity in T2 weighted image and diffusion weighted image in only pancreatic body tumor (Figure 2C,2D).

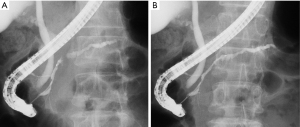

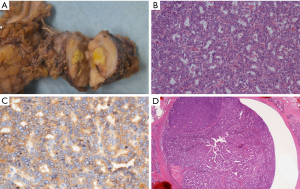

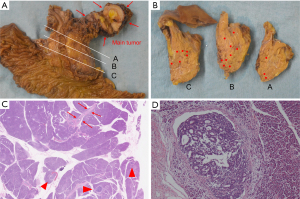

Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP) revealed a craw-like stenosis in the MPD at the pancreatic head and slight dilatation of the caudal MPD (Figure 3A). We inserted a catheter over a guidewire through the stenosis to the caudal MPD (Figure 3B). The stenosed area was brushed and pancreatic juice was collected. In addition, we tried to place a pancreatic drainage tube for serial pancreatic juice aspiration cytological examination but could not because the tube could not exceed the MPD in pancreatic head. We placed a pancreatic spontaneous dislodgement stent for prophylaxis of post-ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) pancreatitis. Although cytological examination of the pancreatic juice did not reveal any malignant cells, we suspected a pancreatic malignant tumor (ductal adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine neoplasm, or PACC). Thus, a pancreaticoduodenectomy was planned. A 35-mm white-grayish mass in the pancreas (head and body) was resected (Figure 4A). Histological examination of the resected specimen revealed tumor cells that were similar to acinar cells with round nuclei, eosinophilic vesicles, and a solid growth pattern (Figure 4B). The lesion was positive for α-antitrypsin (Figure 4C) and negative for chromogranin A. Thus, the patient was diagnosed with PACC. The tumor also involved the MPD (Figure 4D). Furthermore, although the tumor had scattered and engrafted to multiple BDs at downstream of the main tumor, there was no continuity between the scattered tumor and main tumor (Figure 5A-5D). The interval between ERP and surgery was 30 days. At 68 months post-surgery, the patient is alive with no recurrence. We did not conduct a searching for gene alternation including the breast cancer susceptibility genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2 in this patient.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent for publication of this case report and accompanying images was not obtained from the patient or the relatives after all possible attempts were made.

Discussion

We encountered a case of PACC, in which the tumor had disseminated to multiple BDs without any continuity with the main tumor. We performed a literature review using the keywords ‘acinar cell carcinoma’ and ‘case reports’ in the PubMed database. However, we did not find a case that was similar to ours. In our patient, we hypothesized that the main tumor had invaded the MPD, and parts of it had broken off and disseminated to multiple BDs.

Because PACCs are well-circumscribed, they usually displace adjacent structures. However, they can extend into adjacent structures such as the duodenum, spleen, or major blood vessels. Rarely, grossly identifiable finger-like projections can extend beyond the periphery of the main tumor into the pancreatic duct (9).

PACC can reportedly invade the portal vein (10,11), common bile duct (12,13), and MPD, following intraductal growth (14,15). In these cases, the invaded tumor was identified and delineated on CT, and the incision was planned with reference to these images. In contrast, in our patient, the intraductal implantation from the main tumor could not be detected preoperatively because there was no continuity with the main tumor. If the intraductal invasion had occurred in the pancreatic head from a PACC located in the pancreatic tail, we would have performed a distal pancreatectomy, leaving behind the pancreatic head with scattered lesions.

We were not able to determine why this phenomenon occurred. Furthermore, the following questions remain unanswered: Did the tumor naturally peel away? Did the ERCP break apart the tumor? Finally, why did the tumor get implanted in the BDs? In the PACC case reported by Nagata et al., the tumor had metastasized to the intrahepatic bile duct 6 years after the surgery. The metastatic tumor was confined to the intrahepatic bile duct, without any involvement of the hepatic parenchyma or vasculature (12). The patient was found to have an intraductal polypoid growth (IPG) variant of PACC, which had invaded the common bile duct and was accompanied by obstructive jaundice. After a percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage was performed, a pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed (12). The authors suspected that the tumor implantation had occurred during this biliary drainage.

Usually, PACCs metastasize to the liver, lymph nodes, lung, and peritoneum, and they recur 3–15 months after surgery (12). Nagata et al. stated that because the tumor in their patient was slow-growing, it had recurred due to intraductal implantation after a prolonged period of time. Ikeda also reported a PACC case with multiple lesions (16), which were suspected to be intraductal metastases. Thus, the remnant pancreas should be monitored for intraductal metastases.

Although there have been no reports of pancreatic duct relapse, the findings in Nagata et al.’s patient and our patient indicate that PACC may be associated with intrapancreatic ductal metastases. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, cytological examination of the pancreatic juice obtained via ERCP is usually performed. However, we have experienced few cases of intraductal metastasis following ERCP. Because the PACC is soft, it may peel off and disseminate to the BDs. PACC might have any characteristics easy to be implanted to branch ducts. However, these are still unknown.

In most institutions, a fine needle aspiration using endoscopic ultrasonography is used for diagnosing a pancreatic tumor. However, in Japan, some endoscopists fear needle tract seeding to the stomach wall (17) and peritoneum. Thus, for tumors in the pancreatic body and tail, they prefer obtaining pancreatic juice for cytological examination via ERP. We need to be vigilant of relapse by possible intraductal seeding in patients with PACC.

Conclusions

In PACC, a part of the main tumor can break apart and get implanted in multiple BDs. This indicates that postoperative relapses can occur from metastatic lesions in the remnant pancreas.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-511/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-511/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-511/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent for publication of this case report and accompanying images was not obtained from the patient or the relatives after all possible attempts were made.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Al-Hader A, Al-Rohil RN, Han H, et al. Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma: A review on molecular profiling of patient tumors. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:7945-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- La Rosa S, Adsay V, Albarello L, et al. Clinicopathologic study of 62 acinar cell carcinomas of the pancreas: insights into the morphology and immunophenotype and search for prognostic markers. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:1782-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhosale P, Balachandran A, Wang H, et al. CT imaging features of acinar cell carcinoma and its hepatic metastases. Abdom Imaging 2013;38:1383-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Basturk O, Zamboni G, Klimstra DS, et al. Intraductal and papillary variants of acinar cell carcinomas: a new addition to the challenging differential diagnosis of intraductal neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:363-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ciaravino V, De Robertis R, Tinazzi Martini P, et al. Imaging presentation of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Insights Imaging 2018;9:943-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ikeda M, Miura S, Hamada S, et al. Acinar Cell Carcinoma with Morphological Change in One Month. Intern Med 2021;60:2799-806. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sakai A, Takada S, Katano K, et al. Pancreatic Acinar Cell Carcinoma Projected From the Ampulla of Vater With Extensive Intraductal Tumor Growth. Am J Gastroenterol 2023;118:198. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ikezawa K, Urabe M, Kai Y, et al. Comprehensive review of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma: epidemiology, diagnosis, molecular features and treatment. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2024;54:271-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fabre A, Sauvanet A, Flejou JF, et al. Intraductal acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Virchows Arch 2001;438:312-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakayama S, Fukuda A, Kou T, et al. A case of unresectable ectopic acinar cell carcinoma developed in the portal vein in complete response to FOLFIRINOX therapy. Clin J Gastroenterol 2023;16:610-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kida A, Matsuda K, Takegoshi K, et al. Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma with extensive tumor embolism at the trunk of portal vein and pancreatic intraductal infiltration. Clin J Gastroenterol 2017;10:546-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagata S, Tomoeda M, Kubo C, et al. Intraductal polypoid growth variant of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma metastasizing to the intrahepatic bile duct 6 years after surgery: a case report and literature review. Pancreatology 2012;12:23-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kittaka H, Takahashi H, Ohigashi H, et al. Multimodal treatment of hepatic metastasis in the form of a bile duct tumor thrombus from pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma: case report of successful resection after chemoradiation therapy. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2012;6:518-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Imamura M, Kimura Y, Ito H, et al. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas with intraductal growth: report of a case. Surg Today 2009;39:1006-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa T, Ohno E, Mizutani Y, et al. Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma with predominant extension into the main pancreatic duct: A case report. DEN Open 2022;2:e96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ikeda Y, Yoshida M, Ishikawa K, et al. Rare case of acinar cell carcinoma with multiple lesions in the pancreas. JGH Open 2020;4:1242-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kitano M, Yoshida M, Ashida R, et al. Needle tract seeding after endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition of pancreatic tumors: A nationwide survey in Japan. Dig Endosc 2022;34:1442-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]