Cancer metastasis to the upper gastrointestinal tract—a case series

Highlight box

Key findings

• Metastasis to the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract from non-GI cancers is rare and poses significant clinical challenges. This case series highlights unique instances of such metastasis, emphasising the need for interdisciplinary collaboration and personalised treatment approaches to optimise patient outcomes.

What is known and what is new?

• Metastasis to the upper GI tract from non-GI cancers is uncommon.

• This manuscript provides a case series of seven cases and literature review of non-GI cancers metastasising to the upper GI tract.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• The findings presented in this manuscript underscore the need for heightened clinical awareness that these malignancies can metastasise to the GI tract with unusual manifestations. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion in patients with a history of non-GI cancers presenting with new GI symptoms.

• Given the rare occurrence and challenging nature of such metastasis, there should be increased interdisciplinary collaboration between oncologists, gastroenterologists, and surgeons to facilitate timely diagnosis and management. Enhanced diagnostic algorithms, including the use of advanced imaging and endoscopy, may need to be more frequently employed in high-risk cancer patients presenting with unexplained GI symptoms. Furthermore, tailored management strategies and earlier consideration for palliative interventions should be adopted to improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Background

Metastasis, the process by which cancer cells disseminate from their primary site to distant organs, critically impacts cancer progression and outcomes. While metastasis to well-known sites like the liver, lungs, brain, bones, and lymph nodes has been extensively studied, upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract metastasis remains less explored but clinically significant.

Rationale and knowledge gap

Given the rarity and complexity of upper GI tract metastasis from non-GI cancers, there is a need for detailed case studies to enhance understanding and management of these occurrences.

Objective

To present a series of cases highlighting the clinical manifestations, complications, and management of upper GI tract metastasis from non-GI cancers. We present this article in accordance with the AME Case Series reporting checklist (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-532/rc).

Case presentation

Case 1

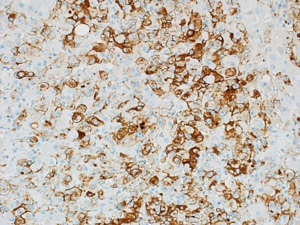

A 72-year-old man diagnosed with renal clear cell carcinoma 8 years ago underwent partial nephrectomy. He experienced recurrence 5 years later, with metastasis to the bones, lungs, and adrenals. Two years later, he presented with upper GI bleeding and melaena. Gastroscopy revealed a large polypoidal lesion in the gastric body with a biopsy confirming ulcerated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (Figure 1) and necessitating a distal gastrectomy. Additionally, his pulmonary metastasis led to tracheal involvement, causing obstructive symptoms. Despite undergoing chemotherapy and radiotherapy, his disease progressed, prompting a transition to palliative care. He subsequently succumbed to complications arising from tracheal involvement.

Case 2

A 72-year-old male patient was diagnosed with clear cell renal carcinoma with pulmonary metastasis and was successfully treated with nephrectomy and on the tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy sunitinib. Ten years later while on surveillance, he experienced abdominal pain, and an abdominal ultrasound revealed a pancreatic lesion. A gastroscopy identified multiple medium-sized polypoid masses in the gastric body, suggestive of metastatic tumours (Figure 2). Due to the high risk of bleeding, no specimens were collected from the gastric masses. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) of the pancreas showed an exophytic lesion in the pancreatic body invading through the gastric wall, with fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy confirming metastatic clear cell carcinoma. Two months later, he suffered a fatal upper GI bleeding event.

Case 3

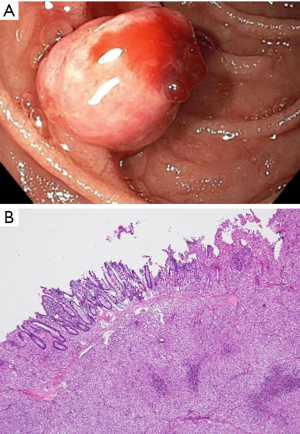

A 69-year-old male with metastatic clear cell carcinoma of the kidney on sunitinib for 2 years, presented with recurrent episodes of haematemesis and melaena. This was on a background of atrial fibrillation with ischaemic stroke for which he was anticoagulated on warfarin. Initial endoscopic assessment identified an oozing gastric ulcer, which was managed with endoscopic adrenaline injection and clipping. He had recurrent melaena a few months after the initial presentation and repeat endoscopy revealed a bleeding duodenal polyp. The histopathology of this lesion revealed metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma to the duodenum (Figure 3A,3B). This was managed with endoscopic mucosal resection and subsequent radiotherapy. Six months after this presentation he had further episodes of melaena requiring frequent blood transfusions. Repeat gastroscopy confirmed presence of gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE), which was managed with argon plasma coagulation. There was no recurrence of the duodenal lesion on repeat endoscopy. Due to disease progression with pulmonary metastasis, Sunitinib was ceased, and second-line therapy with cabozantinib was considered. Unfortunately, the patient’s condition deteriorated due to hospital-acquired pneumonia and fluid overload from end-stage renal failure requiring dialysis. A family meeting with the palliative care team was held, and the patient opted for comfort care. Consequently, further oncological treatment was not pursued, and the patient passed away while receiving palliative comfort measures.

Case 4

A 76-year-old male with prostate cancer and bony metastasis, undergoing 4th line therapy and receiving anticoagulant treatment for pulmonary embolism, presented with recurrent upper GI bleeding. Gastroscopy revealed a duodenal ulcer extending to the pylorus (Figure 4). Attempts to control the bleeding endoscopically were unsuccessful, necessitating laparotomy and oversewing of the bleeding duodenal ulcer. Histopathology of the duodenal ulcer showed metastatic prostate cancer. A month later, he presented with septic shock secondary to acute cholangitis with a computed tomography (CT) scan revealing choledochoduodenal fistula and pneumobilia. Unfortunately, this event proved fatal for him.

Case 5

A 63-year-old male patient had a left ear melanoma excised in 2019. He later presented in 2024 with weight loss and melaena. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan showed segmental areas of small bowel thickening. Gastroscopy revealed two mucosal duodenal nodules (Figure 5), confirmed as metastatic melanoma on histopathology. His GI bleeding proved difficult to manage, requiring multiple blood transfusions. CT angiography did not reveal active arterial haemorrhage but showed irregular areas of mural thickening with aneurysmal dilatation of small bowel segments that were suspected to be the source of slow venous bleeding. He was commenced on nivolumab/ipilimumab and supported with recurrent blood transfusions, leading to the resolution of melaena and stabilization of his haemoglobin levels.

Case 6

A 76-year-old male with non-small cell lung cancer on pembrolizumab presented with abdominal pain. An abdominal CT scan showed thickened small bowel concerning for GI tract metastasis. Gastroscopy with enteroscopy revealed a jejunal ulcer (Figure 6), with histopathology indicating carcinoma of primary lung origin. Two months later, he presented with acute peritonitis and a CT scan showed bowel perforation. Metastatic involvement of the jejunum was suspected and he underwent a laparotomy with bowel resection and anastomosis. Surprisingly the histopathology of the resected perforated segment of the jejunum showed no residual carcinoma, confirming a complete pathological response. He was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) postoperatively and successfully recovered before discharge home. He remains on pembrolizumab with no further disease progression or hospitalisation 12 months later.

Case 7

A 48-year-old male, diagnosed with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, underwent nephrectomy and treatment with sunitinib 10 years earlier. Seven years later, he developed widespread metastasis with involvement of the mediastinum, brain, omentum, and mesentery while on sunitinib and was started on cabozantinib. He presented with GI bleeding secondary to omental metastasis (Figure 7). Subsequently, he underwent surgery for omental metastasis and ischemic bowel due to uncontrolled bleeding despite angiographic embolization of the affected vessel. The histopathology of the small bowel resection confirmed mesenteric metastatic renal cell carcinoma with invasion of the bowel wall. Following successful recovery from surgery, he was discharged home. He then initiated self-funded treatment with lenvatinib and everolimus, which he continued for 2 months before experiencing a fatal episode of haematemesis at home.

Ethical statement

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent for publication of this case series and accompanying images was not obtained from the patients or the relatives after all possible attempts were made.

Discussion

Key findings

Metastasis to the upper GI tract, including the oesophagus, stomach, and intestines, is relatively rare. GI tract metastasis from non-GI cancers, such as breast and lung cancers, are uncommon (1). Autopsy and clinical studies consistently demonstrate low incidence rates. For instance, about 2.5% of post-mortem cases revealed evidence of prostate cancer metastasising to the stomach (2), and a retrospective study of 75,000 patients indicated that approximately 2.7% exhibited metastatic prostate cancer in the GI tract outside of the liver (3,4). Similarly, breast cancer has been associated with rare GI tract metastasis in 1.55% of patients, predominantly affecting the stomach and oesophagus (5). Lung cancer, primarily large cell carcinoma, has also been linked to GI metastasis, with an incidence of approximately 12% in autopsy findings (6). Among solid tumours, melanoma is the most common to metastasise to the GI tract (7).

Metastasis to the upper GI tract from non-GI malignancies can be explained by several biological mechanisms, including haematogenous and lymphatic spread, direct invasion, and peritoneal dissemination. Several studies (8-11) have explored the potential mechanisms of how cancers spread to the upper GI tract. Haematogenous spread is one of the most common routes, particularly via the portal venous system, which connects to the digestive tract, making it a plausible site for metastasis. Tumours with a high affinity for blood vessel invasion, such as renal cell carcinoma and melanoma, are more likely to metastasise to the GI tract through this route.

Certain receptor-ligand interactions also play a critical role in metastatic spread. The overexpression of chemokine receptors, such as C-X-C chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4), has been implicated in guiding metastatic cells to the GI tract, where the corresponding ligand C-X-C chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) is highly expressed. This receptor-ligand interaction facilitates homing and colonisation of metastatic cells in the GI environment (8). These mechanisms highlight the complex interplay between cancer cells and the GI tract microenvironment, suggesting that understanding these pathways can help guide more targeted therapies in managing metastatic involvement in the digestive system.

Metastasis of non-GI cancers to the upper GI tract presents with a spectrum of clinical manifestations. Patients can present with abdominal pain, weight loss, nausea, and overt bleeding. Weight loss stems from early satiety, inadequate calorie intake and heightened catabolism, with nausea and abdominal pain complicating food intake. GI metastasis from other cancers may result in dysphagia when the oesophagus is involved, alongside symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain (12). Notably, metastasis may be seen as nodules or ulcers during endoscopy (13).

Metastasis to the upper GI tract is associated with significant complications. GI bleeding, stemming from cancer-related infiltration and ulceration to the mucosa lining, may lead to anaemia due to ongoing chronic blood loss, however can be a catastrophic complication from acute uncontrollable bleeding. Gastric outlet obstruction, a consequence of tumour growth obstructing the passage between the stomach and duodenum, is a grave concern, which is common in retroperitoneal metastasis but can occur with gastric metastasis as well (12). GI metastasis can result in abdominal symptoms, including abdominal pain, dysphagia, leading to weight loss, fatigue, and muscle wasting due to inadequate oral intake and impaired absorption. These metastases can also occasionally result in fatal hollow viscus perforation.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study lies in its detailed case descriptions and literature review. While the sample size is small, it highlights the variety of such cases (see Table 1).

Table 1

| Case No. | Demographics | Primary malignancy | Site of GI metastasis | Complication due to GI metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 72-year-old male | Renal clear cell carcinoma | Gastric body | Upper GI bleeding and melaena |

| 2 | 72-year-old male | Renal clear cell carcinoma | Gastric body | Abdominal pain and later a fatal upper GI bleeding event |

| 3 | 69-year-old male | Renal clear cell carcinoma | Duodenum | Haematemesis |

| 4 | 76-year-old male | Prostate cancer | Duodenum | Upper GI bleeding and melaena |

| 5 | 63-year-old male | Melanoma | Duodenum | Upper GI bleeding and melaena |

| 6 | 76-year-old male | Non-small cell lung cancer | Jejunum | Acute peritonitis due to bowel perforation |

| 7 | 48-year-old male | Renal cell carcinoma | Omentum | Upper GI bleeding and melaena |

GI, gastrointestinal.

Comparison with similar researches

These findings align with previous studies indicating low incidence rates of upper GI metastasis from non-GI cancers, but provide more contemporary clinical insights into assessment and treatment.

Explanations of findings

Metastasis to the upper GI tract likely results from the unique biological behaviours of certain cancers, emphasising the need for thorough clinical evaluation.

Implications and actions needed

Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for GI metastasis in patients with a history of non-GI cancers presenting with GI symptoms. Interdisciplinary collaboration and tailored treatment approaches are crucial.

Conclusions

In summary, metastasis of non-GI cancers to the upper GI tract is a relatively rare phenomenon. Melanoma, prostate, breast, and lung cancers have been identified as primary culprits, with distinct clinical presentations and complications. Further research is warranted to better understand the underlying mechanisms as to why metastasis occurs in the upper GI tract, diagnostic approaches, and optimal management strategies for these infrequent but clinically significant occurrences.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the AME Case Series reporting checklist. Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-532/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-532/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-532/coif). Geoffrey Peters reports that he participated in advisory boards for BMS and MSD in the last 3 years. Y.K. reports that she received speakers fee from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Novartis, MSD; fees for advisory board with Novartis and travel/accommodation from Pfizer. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement:

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Kaila V, Jain R, Lager DJ, et al. Frequency of metastasis to the gastrointestinal tract determined by endoscopy in a community-based gastroenterology practice. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2021;34:658-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oda Kondo H. Metastatic tumors to the stomach: analysis of 54 patients diagnosed at endoscopy and 347 autopsy cases. Endoscopy 2001;33:507-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: A population-based analysis. Prostate 2014;74:210-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moshref L, Abidullah M, Czaykowski P, et al. Prostate Cancer Metastasis to Stomach: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Curr Oncol 2023;30:3901-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Da Cunha T, Restrepo D, Abi-Saleh S, et al. Breast cancer metastasizing to the upper gastrointestinal tract (the esophagus and the stomach): A comprehensive review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2023;15:1332-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waddingham W, Kamran U, Kumar B, et al. Complications of diagnostic upper Gastrointestinal endoscopy: common and rare - recognition, assessment and management. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2022;9:e000688. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Serrao EM, Costa AM, Ferreira S, et al. The different faces of metastatic melanoma in the gastrointestinal tract. Insights Imaging 2022;13:161. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Calomarde-Rees L, García-Calatayud R, Requena Caballero C, et al. Risk Factors for Lymphatic and Hematogenous Dissemination in Patients With Stages I to II Cutaneous Melanoma. JAMA Dermatol 2019;155:679-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arora S, Harmath C, Catania R, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: metastatic pathways and extra-hepatic findings. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2021;46:3698-707. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nguyen DX, Bos PD, Massagué J. Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9:274-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fidler IJ, Poste G. The "seed and soil" hypothesis revisited. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:808. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katz H, Biglow L, Alsharedi M. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Locally Advanced, Unresectable, and Metastatic Upper Gastrointestinal Malignancies. J Gastrointest Cancer 2020;51:611-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kenny C, Regan J, Balding L, et al. Dysphagia Prevalence and Predictors in Cancers Outside the Head, Neck, and Upper Gastrointestinal Tract. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;58:949-958.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]