Inflammatory pseudotumor-like extranodal classic Hodgkin lymphoma manifesting as bowel perforation in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patient with disseminated leishmaniasis: a case report and approach to differential diagnosis

Highlight box

Key findings

• We report a unique case of classic Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and disseminated leishmaniasis who presented with a small bowel mass and bowel perforation.

• Histologic diagnosis was challenging as the small bowel mass showed a transmural infiltrate of scattered large atypical multinucleated cells surrounded by histiocytes and T-cells. Initial differential diagnosis was wide due to the unusual presentation and cytologic atypia of the tumor cells. Identifying the Hodgkins Reed-Sternberg cells with their unique immunophenotype was key for diagnosis.

What is known and what is new?

• CHL is an extremely common non-AIDS-defining malignancy usually presenting in the lymph node. Primary CHL of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is exceedingly rare.

• Extranodal primary GI tract CHL is exceedingly rare and thus awareness of this entity, which can mimic many other tumors, especially in immunocompromised individuals, is important.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Clinicians should have a higher index of suspicion for primary CHL of the GI tract, especially in HIV and immunocompromised patients.

• Special stains and cultures are often needed for the diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy will induce successful clinical outcome.

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) are more likely to develop cancers (1). These patients are at increased risk of HIV/AIDS-associated lymphomas, with over 40% of these patients developing one of these lymphomas in their lifetime (2,3).

Classic Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) is a hematolymphoid malignancy of germinal center B cells and is defined by the presence of Hodgkin cells including large binucleated or multinucleated Hodgkins Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells in a background of mixed inflammation. The disease accounts for ~15% of all lymphoma diagnoses and the age distribution shows two peaks with one in young adults and another in older adults. Overall, the average age of diagnosis of 39 years (4). Among its subtypes, mixed cellularity CHL accounts for ~25% of cases and is characterized by a diffuse, mixed inflammatory background without sclerosis. It is more often present at advanced stage and is more often associated with HIV infection. Compared to other CHL subtypes, it is strongly associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection and has a relatively worse prognosis (5,6).

The incidence of CHL has increased with the introduction of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) and thus CHL has become an extremely common non-AIDS-defining malignancies. CHL in the setting of HIV is clinically more aggressive, results in more systemic symptoms and has a poor prognosis relative to non-HIV-related CHL (7). CHL usually presents with fever, night sweats, fever, and weight loss in addition to lymphadenopathy. The lymphadenopathy is usually supra-diaphragmatic with cervical, supraclavicular, and axillary being the most common. Primary CHL of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is very rare and previous cases have been linked to inflammatory bowel disease, immunosuppression, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (8,9). Bowel perforation is a rare and life-threatening complication of GI tract lymphoma. A previous retrospective review found only 9% of patients with GI involvement by lymphoma developed a bowel perforation with most perforations occurring after initiation of chemotherapy. Bowel perforation occurring as an initial presentation of CHL has not previously been described in detail (10). We present this case in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-499/rc).

Case presentation

A 51-year-old man with a history of HIV/AIDS and visceral leishmaniasis presented to the emergency department with acute abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. He was diagnosed with HIV 2 years prior after presenting with fatigue and weight loss and was started on HAART (bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir/alafenamide) and was initially compliant with therapy. He had a CD4 count of 201 at initial diagnosis. About a year later, he developed severe abdominal pain and was found to having diffuse lymphadenopathy and pancytopenia. A bone marrow biopsy was performed at the time which found disseminated leishmaniasis. After amphotericin B treatment, repeat bone marrow biopsy a month later did not demonstrate any organisms. An endoscopy and colonoscopy performed 3 months prior to presentation exhibited ileal ulcers. Duodenal and gastric biopsies confirmed the persistent visceral leishmaniasis.

At presentation, he reported having chronic left lower quadrant pain that acutely worsened 2 days prior, and he began having melena. A day prior, he began vomiting profusely and was unable to tolerate any food intake. His review of symptoms was notable for a 5-lb weight loss in the last week and generalized weakness for more than a year. He was tachycardic to 108 bpm and hypotensive to 83/64 mmHg. His physical examination exhibited a chronically ill-appearing man in no acute distress, with distension and tenderness to palpation in the lower quadrants of his abdomen. His labs were notable for leukocytosis (11.13×109/L), microcytic anemia (hemoglobin 7.3 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 66.6 femtoliters, likely due to GI bleeding), and CD4 count of 63×109/L.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of his abdomen and pelvis revealed a small bowel perforation in the left lower quadrant with adjacent free intraperitoneal air and fluid (Figure 1). The patient was scheduled for emergency exploratory laparotomy and abdominal washout. At the time of the laparotomy, he was found to have turbid fluid in the cavity, as well as a 3 cm perforation in the jejunum with an associated mass and regional lymphadenopathy. Two segments of small intestine were resected.

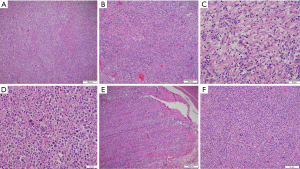

Gross examination of the resected small bowel revealed perforated small bowel with focal thickened wall and adherent lesion with a nodular tan-white smooth cut surface. Histologic examination showed dense fibrosis with prominent transmural nodular lymphoid infiltrate. On high power magnification, the lymphoid infiltrate was heterogenous with many large, atypical cells in the background of small lymphocytes, many eosinophils, neutrophils, and rare plasma cells (Figures 2,3). Most of the large, atypical cells demonstrate lacunar or mummified morphology and complex nuclear features consistent with Reed-Sternberg cell variants, and occasionally demonstrate binucleation and prominent nucleoli, typical of Reed-Sternberg cells. Atypical mitotic figures, tumor necrosis, and fibrosis were present.

Immunohistochemical staining revealed the large, atypical cells expressed CD30 and CD15 (small subset with Golgi accentuation), PAX5 (weak nuclear staining), MUM1 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-in situ hybridization (ISH), and negative for CD3, CD20, CD43, CD45, CD79a, BOB1, and OCT2. These findings suggest the large, atypical cells are B-cell origin with the loss of pan-B-cell antigens, which is the immunophenotype suggestive of HRS cells. The atypical cells had high cell proliferation index Ki-67. The background reactive T cells were CD3 positive and small B cells were positive for CD20, PAX5, BOB1, and CD79a. The background reactive histiocytes were highlighted by CD68 and CD163. Background histiocytes contained numerous small, round uniform intracytoplasmic micro-organisms consistent with leishmania amastigotes.

Overall, the immunophenotypical findings of large, atypical cells which are positive for PAX5 (weak), CD30, CD15 (weak), MUM1, and EBV while negative for CD20 and CD45 support the diagnosis of mixed cellularity CHL.

After diagnosis, the patient was treated with amphotericin B for leishmaniasis. He recovered in the hospital while continuing to be treated with brentuximab (anti-CD30 therapy) with a good response to therapy, further confirming the diagnosis. Further biopsies found involvement of retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Given the diffuse and extra-nodal extension of his disease, using the Cotswolds-modified Ann Arbor classification system, he had stage IV-E disease (11). Using the Internal Prognostic Score (IPS) risk stratification, he had a score of 5 due to his age, gender anemia, low albumin levels, and disease burden (12). This score put him in a high-risk category.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Publication of this case report and accompanying images was waived from patient consent because research involves no risk to the subject and research does not involve any identifying information.

Discussion

Patients with HIV infection develop a progressive decline of their immune system defined by the loss of the CD4+ T-cells. This leads to opportunistic infections as well as an increased risk of certain malignancies. AIDS-defining malignancies include Kaposi’s sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and cervical carcinoma. In addition, patients with HIV/AIDS syndrome are at increased risk for developing Hodgkin lymphoma (13,14).

The increased rates of cancer in patients with HIV are multi-factorial and include a dysregulated immune system, chronic immune stimulation and activation as well as increased risk of infection by oncogenic viruses. The majority of HIV/AIDS-associated lymphoma are B-cell origin and most often possess immunoglobulin chain gene rearrangements. EBV and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) are oncogenic viruses linked to certain HIV/AIDS-associated lymphomas. Burkitt lymphoma (BL), diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and the majority of HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphomas occur in the setting of EBV infection, whereas KSHV is often linked to primary effusion lymphoma (15). In our case, the severe immunosuppression due to HIV, secondary EBV activation, and opportunistic infectious of leishmaniasis are potentially related to the pathogenesis and progression of CHL.

CHL may arise from abdominal lymphadenopathy with clinical presentation as a small bowel mass invading into the adjacent bowel wall. Primary CHL in the GI tract is exceedingly rare. CHL most often presents in the lymph node and extranodal involvement is rarely seen in the spleen, liver, lung, and bone marrow (16). HIV-related CHL is frequently associated with EBV. In this case, because of the unusual presentation including the location of the mass, bowel wall invasion and perforation, and large infiltrative anaplastic cells, a diagnosis of CHL needs to be carefully distinguished from its mimics, such as histiocytic variant of inflammatory pseudotumor, inflammatory pseudotumor with malignant transformation, histiocytic sarcoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), DLBCL, T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B cell lymphoma and less likely pleomorphic sarcoma (Table 1).

Table 1

| Disease | Clinical features | Histopathology | Immunohistochemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory pseudotumor (IMT) | Benign with rare malignant transformation, can occur in response to infection, young adults and children, more likely extrapulmonary site than non-HIV-related | Infiltrative mass of spindled myofibroblasts, larger ganglion-like cells, prominent inflammatory cells including plasma cells, lymphocytes and histiocytes | Vimentin+, smooth muscle actin+, ALK+ (most cases) |

| CHL | Hematolymphoid malignancy, nodal and rarely extra-nodal, present with lymphadenopathy and B symptoms | Large, atypical cells with multiple nuclei (HRS cells) in a background of inflammatory cells | HRS cells CD15+/−, CD30+, PAX5+ (weak), MUM1+ and CD20−/focal weak+, CD45− |

| Histiocytic sarcoma | Mainly extra-nodal, rare, aggressive, can transdifferentiate from B cell lymphoma, present with B symptoms | Diffuse infiltrate of large histiocytes with variable pleomorphism and often multinucleated giant cells, mixed inflammatory background can be present | CD68+, CD163+, lysozyme+, CD15+, CD45+, negative for B and T cell markers |

| HIV associated Kaposi sarcoma | Malignant vascular neoplasm due to HHV8, skin most common site | Spindled endothelial cells with minimal atypia forming dilated to slit-like vascular channels in a background of extravasated red blood cells, hemosiderin and plasma cells | HHV8+ in 100% of cases, CD34+, CD31+, D2-40+ |

| Large B cell lymphoma | Most common AIDS/HIV associated lymphoma, nodal, GI tract is most common extra-nodal site, presents as rapidly enlarging mass | Diffuse sheet-like infiltrate of pleomorphic large cells with atypical nuclei, can have large inflammatory background | CD19+, CD20+, PAX5+, CD79a+, CD45+, and occasional BCL2+, BCL6+/CD10+ |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; IMT, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; CHL, classic Hodgkin lymphoma; HRS, Hodgkins Reed-Sternberg; GI, gastrointestinal.

Inflammatory pseudotumor [inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT)] is a rare neoplasm of spindled myofibroblasts admixed with inflammatory cells and can occur in many organ systems. In most cases, it is a benign though it can mimic many malignancies. Etiology is unknown and can occur in response to infections or autoimmune reactions. It most often occurs in the lung though it can occur elsewhere including GI tract (17). This tumor often occurs in children and young adults and is typically circumscribed and microscopically infiltrative. Histologically while the spindled myofibroblasts are often cytologically bland but can have variable cytologic atypia. Larger anaplastic cells have cytoplasm that is eosinophilic to amphophilic as well as large nucleoli. There are prominent inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and plasma cells with foamy histiocytes in the background (18). It is generally divided into three histologic patterns with the most common being the fibrous histiocytic pattern followed by the organizing pneumonia and lymphohistiocytic pattern. By immunohistochemistry, the cells are positive for vimentin, smooth muscle actin, and often anaplastic lymphoma kinase 1 (ALK1).

HIV-associated IMTs are frequently extrapulmonary relative to non-HIV-associated (19). On rare occasions, IMT may exhibit malignant transformation. IMTs often harbor a clonal rearrangement of ALK gene on chromosome 2p23 leading to overexpression of ALK (20). Cases that lack ALK rearrangement and do not express ALK have a worse prognosis and are more aggressive than ALK positive tumors (21). ALK negative IMTs tend to occur in older patients and have greater atypical histological features. These features include hypercellularity, abundant large ganglion-like cells, necrosis multinucleated or anaplastic giant cells, nuclear pleomorphism, and atypical mitosis. The epithelioid form of IMT is an intra-abdominal sarcoma and occurs more often in male patients. Histologically this variant has myxoid stroma and conspicuous neutrophils in addition to perinuclear or nuclear membrane ALK staining. This variant is aggressive, has a high rate of recurrence, and can be fatal (22). Because of our patient’s clinical history of systemic leishmaniasis, infectious-induced inflammatory pseudotumor was high on the differential diagnosis. Histologically, the background colonic mucosa exhibited marked inflammatory and histiocytic infiltrate with spindled cells and fibrosis which are features of inflammatory pseudotumor (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry helped distinguish our case with the cells being negative for vimentin, smooth muscle actin, and ALK.

Histiocytic sarcoma is a rare, mainly extra nodal malignant proliferation of mature histiocytes often involving the skin, soft tissue, lung, and central nervous system (23). Histologically, the tumor is composed of an infiltrate of large cells resembling mature histiocytes with significant atypia. The cells have oval or atypical nuclei, vesicular chromatin, large nucleoli with occasional grooves and plump eosinophilic cytoplasm. Multinucleated giant tumor cells, increased mitotic figures, and necrosis can be present. Often there is a mixed inflammatory background composed of reactive lymphocytes and benign histiocytes. The malignant histiocytes are diffusely show staining for histiocytic markers (CD68, CD163, lysozyme), occasionally CD15 and CD45 and are negative for B- and T-cell markers and CD30 (24).

Patients with HIV/AIDS infection are at increased risk of developing malignant lymphomas. While the rise in anti-retroviral therapy has resulted in the decline of the majority of non-Hodgkin lymphomas, it is still the most common cause of mortality in HIV/AIDS patients relative to the those without HIV/AIDS. Therefore, lymphoma was also high on our differential.

DLBCL is the most frequent adult non-Hodgkin lymphoma and most often present in the lymph nodes but 40% are purely extranodal with the GI tract being the most common (18%) (25). It presents as a rapidly enlarging mass of diffuse sheet-like infiltrate of pleomorphic medium to large cells with atypical nuclei, prominent nucleoli and vesicular chromatin that can mimic HRS cells. However, the atypical cells in DLBCL have a different immunophenotype than HRS cells. The cells express B cell markers including CD20, CD19, PAX5, CD79a, and sometimes BCL2, CD10 and/or BCL6 and MYC. They do not express CD15 or CD30. In our case the large, atypical cells were negative for CD20 and CD79a with weak positivity for PAX5, ruling out this neoplasm.

T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B cell lymphoma is often in middle-aged adults with a male predominance and typically involves the lymph nodes but can involve the marrow. Histologically it is composed of large, atypical B cells surrounded by T cells and histiocytes. The neoplastic B cells must compose <10% of the total cells (26). The large neoplastic B cells have a vary in morphology and immunophenotypic features and can be HRS cell-like in which they are large multinucleated cells with pleomorphic nuclei, central nucleoli, and sometimes binucleated. The neoplastic B cells are surrounded by small reactive T cells and clusters of bland histiocytes. Immunophenotypically, the large B cells are positive for pan B cell markers (CD20, CD79a, PAX5, OCT2/BOB1) and negative for CD15 and CD30.

ALCL is a malignancy of mature T-cells and features cohesive sheets of large, atypical cells. Classically the malignant cells have curved nuclei with a prominent Golgi and are CD30 positive. In addition, the cells stain positive for cytotoxic T-cell markers (TIA1, granzyme B, perforin) and sometimes ALK1. Aberrant loss of pan-T-cell antigens CD3, CD5, and CD7 is common but CD2, CD4, and CD43 are positive in a significant proportion of cases. Rarely, ALCL can have a Hodgkin-like pattern similar to the nodular sclerosing subtype of CHL. In this case, the infiltrate is nodular and contains inflammatory cells intermixed with large, atypical cells that can resemble HRS cells with bands of fibrosis. The Hodgkin-like pattern is rare (less than 5%) and overall resembles nodular sclerosis CHL, with nodules containing polymorphous inflammatory cells and scattered HRS-like cells surrounded by bands of fibrosis (27).

Conclusions

In this case, a patient with HIV/AIDS and disseminated leishmaniasis presented with a small bowel mass leading to bowel perforation. Histologically, the small bowel mass showed a transmural infiltrate composed of large atypical multinucleated cells in a background of histiocytes and T cells. Initial differential diagnosis was wide due to the unusual presentation and cytologic atypia of the tumor cells. CHL has many overlapping features with other entities and thus the presence of HRS cells with their unique immunophenotype of positivity for CD15 and CD30 and loss of multiple B-cell antigens in a characteristic cellular microenvironment was key for diagnosis. It is critical to identify CHL in HIV/AIDS patients for appropriate treatment in the condition of immunodeficiency and disseminated opportunity infection. Extranodal primary GI tract CHL is exceedingly rare and usually has a good prognosis with anti-HIV and anti-CD30 therapy. Awareness of this rare entity which can be a mimicker and diagnostic pitfall for variety of malignancy with histiocytic variant of inflammatory pseudotumor-like features, especially in immunocompromised individuals, is important. The selected special stains, tissue cultures, and serology study are helpful for the diagnosis, and antimicrobial therapy will induce successful clinical outcome. Overall, the unusual combination of acute clinical presentation, leishmaniasis, and HIV made the histological recognition of CHL crucial to avoid misdiagnosis and guide successful clinical management.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-499/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-499/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-499/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Publication of this case report and accompanying images was waived from patient consent because research involves no risk to the subject and research does not involve any identifying information.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Yarchoan R, Uldrick TS. HIV-Associated Cancers and Related Diseases. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1029-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cesarman E. Pathology of lymphoma in HIV. Curr Opin Oncol 2013;25:487-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carroll V, Garzino-Demo A. HIV-associated lymphoma in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: shifting the immunological landscape. Pathog Dis 2015;73:ftv044. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Munir F, Hardit V, Sheikh IN, et al. Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma: From Past to Future-A Comprehensive Review of Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Advances. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:10095. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gulley ML, Eagan PA, Quintanilla-Martinez L, et al. Epstein-Barr virus DNA is abundant and monoclonal in the Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin's disease: association with mixed cellularity subtype and Hispanic American ethnicity. Blood 1994;83:1595-602. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carbone A, Gloghini A. Epstein Barr Virus-Associated Hodgkin Lymphoma. Cancers (Basel) 2018;10:163. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spina M, Carbone A, Gloghini A, et al. Hodgkin's Disease in Patients with HIV Infection. Adv Hematol 2011;2011:402682. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zarate-Osorno A, Medeiros LJ, Kingma DW, et al. Hodgkin's disease following non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. A clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of nine cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1993;17:123-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kumar S, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-positive primary gastrointestinal Hodgkin's disease: association with inflammatory bowel disease and immunosuppression. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:66-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vaidya R, Habermann TM, Donohue JH, et al. Bowel perforation in intestinal lymphoma: incidence and clinical features. Ann Oncol 2013;24:2439-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lister TA, Crowther D, Sutcliffe SB, et al. Report of a committee convened to discuss the evaluation and staging of patients with Hodgkin's disease: Cotswolds meeting. J Clin Oncol 1989;7:1630-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hasenclever D, Diehl V. A prognostic score for advanced Hodgkin's disease. International Prognostic Factors Project on Advanced Hodgkin's Disease. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1506-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jacobson CA, Abramson JS. HIV-Associated Hodgkin's Lymphoma: Prognosis and Therapy in the Era of cART. Adv Hematol 2012;2012:507257. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsimberidou AM, Sarris AH, Medeiros LJ, et al. Hodgkin's disease in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: frequency, presentation and clinical outcome. Leuk Lymphoma 2001;41:535-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gloghini A, Dolcetti R, Carbone A. Lymphomas occurring specifically in HIV-infected patients: from pathogenesis to pathology. Semin Cancer Biol 2013;23:457-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang HW, Balakrishna JP, Pittaluga S, et al. Diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma in the modern era. Br J Haematol 2019;184:45-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hornick J. Soft tissue tumors. Fibroblastic and myofibroblastic tumors. Soft Tissue and Bone Tumors. 5th ed. 2020. [Cited 2024 June 22nd]. Available online: https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/chaptercontent/33/43

- Goldblum JR, Weiss SW, Folpe AL. Enzinger and Weiss's soft tissue tumors. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021:129-200.

- Aboulafia DM. Inflammatory pseudotumor causing small bowel obstruction and mimicking lymphoma in a patient with AIDS: clinical improvement after initiation of thalidomide treatment. Clin Infect Dis 2000;30:826-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Griffin CA, Hawkins AL, Dvorak C, et al. Recurrent involvement of 2p23 in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Cancer Res 1999;59:2776-80. [PubMed]

- Coffin CM, Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: comparison of clinicopathologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features including ALK expression in atypical and aggressive cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:509-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mariño-Enríquez A, Wang WL, Roy A, et al. Epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma: An aggressive intra-abdominal variant of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with nuclear membrane or perinuclear ALK. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:135-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kommalapati A, Tella SH, Go RS, et al. Predictors of survival, treatment patterns, and outcomes in histiocytic sarcoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2019;60:553-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pan Z, Xu ML. Histiocytic and Dendritic Cell Neoplasms. Surg Pathol Clin 2019;12:805-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sukswai N, Lyapichev K, Khoury JD, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma variants: an update. Pathology 2020;52:53-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022;36:1720-48.

- Amador C, Feldman AL, How I. Diagnose Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2021;155:479-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]