Conversion resection of initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma associated with steatohepatitis through hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy-transarterial chemoembolization and systemic therapy: a case report

Highlight box

Key findings

• A 61-year-old male with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and steatohepatitis was treated with a combination of hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy combined with transarterial chemoembolization (HAIC-TACE), lenvatinib, and sintilimab. The treatment led to significant tumor reduction and no viable tumor was found post-surgery. The patient remains tumor-free six months after curative liver resection. This case suggests multimodality therapy as a viable option for advanced HCC in patients with steatohepatitis.

What is known and what is new?

• Locoregional therapy may exacerbate tumor tissue hypoxia, stimulate angiogenesis, and may lead to tumor metastasis, whereas combination with anti-angiogenic agents may counteract the adverse results of local therapy. In addition, alterations in the tumor microenvironment facilitate the action of immune checkpoint inhibitors. These theories are well practiced in viral hepatitis-associated HCC, as confirmed by many previous cases as well as cohort studies.

• Reports on the use of combination therapies for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)-HCC are infrequently encountered. Through this case presentation, we illustrate that such therapeutic approaches may continue to yield positive outcomes within this demographic, exhibiting a favorable safety profile.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• With the increasing incidence of NASH-HCC, treatment of these populations should be of heightened concern. The successful translation of this case provides some possible options for treatment selection, and again, this provides ideas and direction for subsequent clinical trial.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) poses a significant global health challenge, being the sixth most prevalent cancer and the third highest cause of cancer-related mortality (1).

At their first visit, many patients are diagnosed with advanced tumors that are not amenable to immediate surgical resection. This is often due to the extensive nature of the tumors and the high likelihood of recurrence, especially when macrovascular invasion is present.

In recent years, systemic therapies have transformed advanced HCC into a less daunting prospect, offering hope with their impressive objective response rates (ORRs). Systemic drug therapy mainly refers to the combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and anti-vascular targeted drugs. The IMbrave 150 trial has heralded a new era in systemic therapy for HCC, reporting positive results for the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab, thus revolutionizing treatment approaches with an immuno-combination targeted drug regimen (2). However, the LEAP-002 study did not meet expectations with the combination of pembrolizumab and lenvatinib (3). As a result, ongoing research is focused on integrating additional locoregional therapies to potentiate tumor responses. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) stands as the standard of care for intermediate to advanced HCC, yet its effectiveness is constrained in patients with extensive bi-lobar disease or macrovascular invasion (4). Hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) operates on a different principle than TACE, offering sustained perfusion of chemotherapy that enhances its tumoricidal effect (5).

In this case, a multifaceted treatment plan combining HAIC-TACE, lenvatinib, and sintilimab was utilized, resulting in significant tumor downstaging for an HCC patient in a steatosis background and presenting with portal vein tumor thrombus (PVTT). This multimodal strategy achieved significant tumor downstaging, facilitating curative-intent surgery and highlighting its potential as an effective therapy for advanced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)-related HCC. We present this case in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-640/rc).

Case presentation

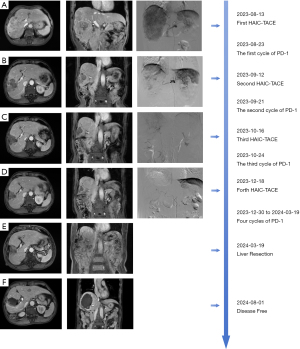

A 61-year-old male visited the hospital with right upper abdominal pain who free of viral hepatitis and alcohol consumption, but overweight with a body mass index (BMI) of 25.2 kg/m2. Physical examination revealed a mass in the right upper abdomen. Ultrasonography suggests diffuse echogenic enhancement of the liver and fatty liver is considered, and a hypoechoic area (12.1 cm × 7.3 cm) was observed (Figure S1). A massive right hepatic lobe tumor (12.6 cm × 7.2 cm) with PVTT in the right branch was confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 1A). Given the increased levels of serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and des-gamma-carboxyprothrombin (DCP), along with normal results from tests for immune-related liver diseases, including liver function tests, antinuclear antibody, anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody, and anti-soluble liver antigen, a preliminary diagnosis of NASH-associated HCC was made. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

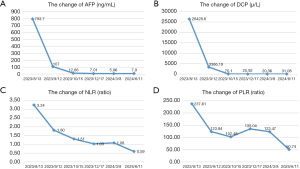

Liver resection was deemed infeasible due to the risk of narrow margins and potential post-hepatectomy liver failure. Following multidisciplinary team (MDT) deliberation, a strategy combining HAIC-TACE with lenvatinib and sintilimab was selected. Initiating treatment on August 13, 2023, with the FOLFOX4 (5-fluorouracil + oxaliplatin + leucovorin calcium) regimen for HAIC. Then conventional TACE (lipiodol and epirubicin) was performed, followed by lenvatinib (12 mg per day based on body weight, and discontinued during HAIC-TACE) and sintilimab (200 mg intravenously every 21 days). Before the second treatment cycle, a significant reduction in tumor size and PVTT was observed (Figure 1B). Then the patient started the second cycle of treatment on September 12. Encouraged by the positive response, the patient underwent a third cycle of treatment on October 16 (Figure 1C). In December, MRI showed continued tumor and thrombus reduction, and the fourth cycle of treatment was completed on December 18 (Figure 1D). By March 2024, the tumor had shrunk to 5 cm, with the thrombus retreating to the right anterior branch of the portal vein (Figure 1E). Between December 30, 2023, and March 19, 2024, patients received a total of 4 cycles of sintilimab therapy and lenvatinib. Upon MDT review, the patient was determined to be safe to undergo surgery and underwent open hepatectomy in sections 5 and 8 on March 13, 2024. The pathology report described revealed extensive necrosis in the tumor region, and the adjacent liver tissue showed chronic hepatitis (G2S1) with steatosis, and no viable tumor tissue was identified (Figure S2). The patient was discharged on the 8th postoperative day and received adjuvant lenvatinib and sintilimab for a total of 8 cycles. Treatment-related adverse reactions were evaluated using CTCAE 5.0 throughout the treatment process. The patient experienced mild nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and hypothyroidism, without other sever adverse reactions. There were no surgical complications throughout the perioperative period. At the 5-month follow-up, no signs of recurrence were detected (Figure 1F). Throughout the course of treatment, AFP and DCP have declined significantly with tumor shrinkage, and have been reduced to within normal levels after the fourth cycle of treatment (Figure 2A,2B).

Patient perspective

When I was told that I had terminal liver cancer, I felt like the sky was falling. I had never imagined that after receiving conservative treatment, the tumor could shrink and be removed surgically, allowing me to return to a normal life. I am lucky, and I am grateful to the medical staff for their dedicated care and selfless commitment.

Discussion

As the standard therapy for intermediate stage HCC, the efficacy and safety of TACE has been widely recognized in clinical practice, but its limited effectiveness in HCC combined with PVTT, which unfortunately can account for as much as 44%-62.2% of HCC (6). In contrast, HAIC infused chemotherapeutic agents can act on both the tumor and PVTT, and some studies find HAIC-TACE has a higher conversion resection rate than TACE alone (5,7-9). As localized treatments directly targeting the tumor, HAIC-TACE can also aggravate tumor tissue hypoxia, stimulating angiogenesis and potentially leading to tumor metastasis (10). Therefore, the combination with antiangiogenic drugs is theoretically feasible to counteract the adverse results of locoregional therapy (11,12). ICIs have been used widely in HCC in recent years, however, positive results have not been achieved with ICIs alone (13). To date, ICIs with anti-vascular targeted agents have only yielded promising results with IMbrave150 (2), with other combinations ending in failure, which has led to a trend toward combinations with locoregional therapy. Chen et al. reported significantly superior ORR of 72% in unresectable HCC with PVTT treated with the combination of HAIC-TACE, lenvatinib, and tislelizumab (14). Some other recent studies have echoed these promising results with combination therapies, as detailed in Table 1 (15-19). In our case, the incorporation of HAIC-TACE into the treatment plan led to a dramatic reduction in tumor size from 12.6 cm to 5 cm, enhancing the feasibility of resection.

Table 1

| Study | Interventions | BCLC-stage | ORR | CRR | AEs† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuan et al., 2023 (15) | HAIC-TACE + TKIs + PD-1 (n=95) vs. TACE (n=179) | C | 51.8% vs. 6.6% | 46.3% vs. 4.5% | Grade 3–4 AEs |

| Abdominal pain (20.1% vs. 33.3%) | |||||

| Pang et al., 2024 (16) | HAIC-TACE + TKIs + PD-1 (n=62) | B/C | 67.70% | 27.40% | Grade 1–2 AEs |

| Transaminitis (56.4%) | |||||

| Nausea and vomiting (43.5%) | |||||

| Thrombocytopenia (37.1%) | |||||

| Huang et al., 2024 (17) | HAIC-TACE + TKIs + PD-1 (n=63) vs. TACE + TKIs + PD-1 (n=60) | B/C | 20.6% vs. 13.3% | – | Grade 1–2 AEs |

| Nausea/vomiting (34.8% vs. 18.8%) | |||||

| Neutropenia (20.3% vs. 7.8%) | |||||

| Thrombocytopenia (29.0% vs. 12.5%) | |||||

| Zhao et al., 2024 (18) | HAIC-TACE + TKIs + PD-1 (n=28) | C | 64.3% | 35.7% | Grade 1–2 AEs |

| Neutropenia (100%) | |||||

| Thrombocytopenia (78.6%) | |||||

| pain (67.9%) | |||||

| Huang et al., 2024 (19) | HAIC-TACE + PD-L1 + Anti-VEGFR (n=92) vs. HAIC-TACE + TKIs + PD-1 (n=96) | C | 62.0% vs. 70.8% | 19.6% vs. 15.6% | Grade 1–2 AEs |

| Neutropenia (23.9% vs. 39.6%) | |||||

| Hemoglobin decrease (50.0% vs. 68.8%) |

†, the most common adverse effects with dual or triple therapy. HAIC-TACE, hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy combined with transarterial chemoembolization; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; ORR, objective response rate; CRR, conversion resection rate; AEs, adverse effects; TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors; PD-1, programmed death-1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Moreover, systemic therapies like immunotherapy may cause unusual responses, including pseudo-progression and delayed effects, complicating traditional tumor size-based efficacy evaluations. There is an urgent need to discover new predictive biomarkers and to determine the subset of HCC patients who are most likely to benefit from systemic therapy. Potential predictors include programmed death-ligand 1 expression, tumor mutational burden, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) (20,21). Notably, serum NLR and PLR are of interest due to their ease of measurement. In the aforementioned case, a decrease in serum NLR from 3.24 to 1.08 (Figure 2C) and in PLR from 237.61 to 123.47 (Figure 2D) suggests the merit of further investigation into using NLR and PLR as predictive indicators. The primary concern with combining multiple treatment modalities is the potential for adverse effects, particularly in HCC cases with PVTT, where liver function is already compromised. In the studies summarized in Table 1 (15-19), the combination therapy did not result in any intolerable adverse events. The most frequently reported issues were nausea and vomiting, pain, and granulocytopenia. In this particular instance, the patient tolerated the combination therapy well, with only gastrointestinal discomfort, mild hypothyroidism and abdominal pain. Interestingly, hypothyroidism has been linked to a higher response rate to ICI therapy in previous studies (22-24).

In conclusion, there have been many case reports and cohort studies of successful conversion therapy with combination therapy (25-27). However, it remains uncertain whether there are differences in treatment response across various etiologies of HCC, and there is a notable absence of large-scale studies focusing on HCC with a background of fatty liver disease. With hepatitis B vaccination, viral hepatitis B-associated HCC is trending lower in the future, while the prevalence of NASH-related HCC is increasing (28). Currently, there is controversy about the effectiveness of ICIs in the treatment of NASH-HCC. The established view is that this type of HCC is associated with a poor response to immunotherapy, possibly due to NASH-associated aberrant T-cell activation causing tissue damage and resulting in impaired immune surveillance (29). In contrast, a recent study published in Nature found that obesity-associated inflammatory cytokines promote the expression of programmed death-1 (PD-1) by tumor-associated macrophages, thereby impairing anti-tumor immune surveillance. While this promotes cancer development, it also gives anti-PD-1 therapies more room to maneuver (30,31). In the context of the current study, combination therapy may be a more effective strategy for NASH-HCC, regardless of the role of PD-1 inhibitors. The successful downstaging and resection in this case offer promising new avenues for therapeutic decision-making in advanced NASH-HCC. Nonetheless, case reports inherently have limitations and need to be confirmed by larger sample size studies in the future.

Conclusions

In this case report, we documented the successful conversion of an HCC patient with a steatohepatitis background who underwent HAIC-TACE in combination with sintilimab and lenvatinib, which demonstrated excellent antitumor effects and no serious adverse events occurred. The experience of this case provides more possible options for the treatment of HCC in a steatohepatitis background.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-640/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-640/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-640/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Guo Q, Zhu X, Beeraka NM, et al. Projected epidemiological trends and burden of liver cancer by 2040 based on GBD, CI5plus, and WHO data. Sci Rep 2024;14:28131. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gordan JD, Kennedy EB, Abou-Alfa GK, et al. Systemic Therapy for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2024;42:1830-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Llovet JM, Kudo M, Merle P, et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab versus lenvatinib plus placebo for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (LEAP-002): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2023;24:1399-410. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singal AG, Llovet JM, Yarchoan M, et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2023;78:1922-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao M, Guo Z, Zou YH, et al. Arterial chemotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma in China: consensus recommendations. Hepatol Int 2024;18:4-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou XH, Li JR, Zheng TH, et al. Portal vein tumor thrombosis in hepatocellular carcinoma: molecular mechanism and therapy. Clin Exp Metastasis 2023;40:5-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ding Y, Wang S, Qiu Z, et al. The worthy role of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy in combination with anti-programmed cell death protein 1 monoclonal antibody immunotherapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol 2023;14:1284937. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin Z, Chen D, Hu X, et al. Clinical efficacy of HAIC (FOLFOX) combined with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors vs. TACE combined with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors in the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus and arterioportal fistulas. Am J Cancer Res 2023;13:5455-65. [PubMed]

- Zheng K, Zhu X, Fu S, et al. Sorafenib Plus Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy versus Sorafenib for Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Major Portal Vein Tumor Thrombosis: A Randomized Trial. Radiology 2022;303:455-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Z, Li Q, Liang B. Hypoxia as a Target for Combination with Transarterial Chemoembolization in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2024;17:1057. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rimassa L, Finn RS, Sangro B. Combination immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2023;79:506-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tamai Y, Fujiwara N, Tanaka T, et al. Combination Therapy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors with Locoregional Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:5072. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ruli TM Jr, Pollack ED, Lodh A, et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Their Hepatic-Related Side Effects: A Review. Cancers (Basel) 2024;16:2042. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen S, Shi F, Wu Z, et al. Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy Plus Lenvatinib and Tislelizumab with or Without Transhepatic Arterial Embolization for Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Portal Vein Tumor Thrombus and High Tumor Burden: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2023;10:1209-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuan Y, He W, Yang Z, et al. TACE-HAIC combined with targeted therapy and immunotherapy versus TACE alone for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumour thrombus: a propensity score matching study. Int J Surg 2023;109:1222-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pang B, Zuo B, Huang L, et al. Real-world efficacy and safety of TACE-HAIC combined with TKIs and PD-1 inhibitors in initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Int Immunopharmacol 2024;137:112492. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang Z, Wu Z, Zhang L, et al. The safety and efficacy of TACE combined with HAIC, PD-1 inhibitors, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study. Front Oncol 2024;14:1298122. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao W, Liu C, Wu Y, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE)-hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) combined with PD-1 inhibitors plus lenvatinib as a preoperative conversion therapy for nonmetastatic advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a single center experience. Transl Cancer Res 2024;13:2315-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang Z, Chen T, Li W, et al. PD-L1 inhibitor versus PD-1 inhibitor plus bevacizumab with transvascular intervention in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Exp Med 2024;24:138. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang C, Zhang H, Zhang L, et al. Evolving therapeutic landscape of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;20:203-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang N, Yang X, Piao M, et al. Biomarkers and prognostic factors of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor-based therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomark Res 2024;12:26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Chen J, Liu H, et al. The incidence of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) and their association with clinical outcomes in advanced renal cell carcinoma and urothelial carcinoma patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev 2024;129:102787. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luongo C, Morra R, Gambale C, et al. Higher baseline TSH levels predict early hypothyroidism during cancer immunotherapy. J Endocrinol Invest 2021;44:1927-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muir CA, Menzies AM, Clifton-Bligh R, et al. Thyroid Toxicity Following Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Treatment in Advanced Cancer. Thyroid 2020;30:1458-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giorgio A, De Luca M. Conversion therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma to improve treatment strategies for intermediate and advanced stages. World J Clin Cases 2024;12:6241-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin ZP, Hu XL, Chen D, et al. Efficacy and safety of targeted therapy plus immunotherapy combined with hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy (FOLFOX) for unresectable hepatocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2024;30:2321-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu XK, Yang LF, Chen YF, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation combined with lenvatinib plus camrelizumab as conversion therapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a single-arm, multicentre, prospective study. EClinicalMedicine 2024;67:102367. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah PA, Patil R, Harrison SA. NAFLD-related hepatocellular carcinoma: The growing challenge. Hepatology 2023;77:323-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Zhu L, Liang C, et al. Targeting N6-methyladenosine reader YTHDF1 with siRNA boosts antitumor immunity in NASH-HCC by inhibiting EZH2-IL-6 axis. J Hepatol 2023;79:1185-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bader JE, Wolf MM, Lupica-Tondo GL, et al. Obesity induces PD-1 on macrophages to suppress anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2024;630:968-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miao Y, Li Z, Feng J, et al. The Role of CD4(+)T Cells in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25:6895. [Crossref] [PubMed]