Is radix ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery effective in Japanese-Style D3 radical lymph node dissection for sigmoid colon and rectal cancer surgery?—a single-center retrospective analysis since 2002

Highlight box

Key findings

• This study compared outcomes between two surgical approaches for stage II/III primary sigmoid colorectal cancer: inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) root ligation (complete dissection) and IMA preservation.

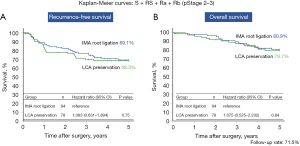

• No significant differences in 5-year recurrence-free survival (5Y-RFS) or overall survival (5Y-OS) were found between the complete ligation group and left colonic artery preservation group, with 5Y-RFS of 69.1% vs. 68.3% and 5Y-OS of 80.9% vs. 79.7%, respectively.

• Postoperative complications were observed, with a trend suggesting higher rates in the IMA complete ligation group.

What is known and what is new?

• Previous studies suggested that D3 dissection with IMA ligation could increase postoperative complications and colonic ischemia without improving survival outcomes for gastrointestinal cancers.

• This study provides evidence that neither complete IMA ligation nor preservation significantly impacts survival outcomes in sigmoid colorectal cancer, challenging the necessity of complete dissection in surgical practice.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• The findings suggest that IMA preservation during surgery may be sufficient for managing stage II/III sigmoid colorectal cancer, potentially reducing complications associated with IMA root ligation.

• Surgical protocols may need to be revised to prioritize IMA preservation over complete ligation in order to minimize postoperative complications and improve patient quality of life, while maintaining comparable survival outcomes.

Introduction

Background

The original Japanese lymph node dissection was defined as D3 dissection, which indicates lymph node dissection at the root of the main trunk artery, with a number in the range of 3 at the end indicating the common area to be resected (1). This means that the ileocecal artery root (#203) for cecal cancer, right colonic artery root (#213) for ascending colon cancer, middle colonic artery root (#223) for transverse colon cancer, and inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) root (#253) for descending colon cancer/sigmoid colon cancer should be securely ligated and dissected. In RS/Ra/Rb rectal cancer, treatment of the root of the IMA (#253) is recommended for T2 [muscularis propria (MP)] cancers and deeper tumors (2). Recently, the importance of complete mesocolic excision/total mesorectal excision (CME/TME) and central vascular ligation (CVL) has been reported in Europe and the United States. However, the difference between CME and Japanese-Style D3 dissection is currently unclear (3-6). However, the differences between D3 dissection and Japanese-Style D3 dissection remain unclear. In right-sided colon resection, the anterior trunk of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) is resected and dissected as thoroughly as possible. For the transverse colon, the anterior portion of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) is completely dissected down to the inferior border of the pancreatic body. In the left hemicolon, either root ligation of the IMA or preservation of the IMA root, along with a systematic complete dissection around #253, is conducted. Recently, left D3 dissection with ligation and dissection at the root of the IMA colic artery/vein has been reported (7). In the left hemicoeliac, a D3 dissection preserving the IMA with ligation and dissection at the root of the IMA colic A/V has been reported in recent years. Ligation at the IMA root is more straightforward in sigmoid colon cancer, and the same dissection procedure is applied in rectosigmoid/upper rectum/lower rectum (RS/Ra/Rb) lower rectal cancer. Particularly in laparoscopic resection of colorectal cancer, exposing and clipping the root of the blood vessel facilitates the demarcation of the apex for fan-shaped resection via TME, thereby standardizing the surgical resection area. Nonetheless, the classification of the metastatic regions by numbering—N1 area (N1/marginal arcade node), N2 area (N2/middle lymph node), N3 area (N3/root of the main artery), and N4 area (N4/para-Ao LN)—is a practice unique to Japan. The 7th edition of the tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) classification (2006) also adopted this numbering system, unifying the categorization of metastases in line with earlier TNM classifications. Primarily, N1–3 classification relies on the number of metastatic lymph nodes (8).

Rationale and knowledge gap

In contrast, in Japan, no improvement in survival with extended dissection up to the D3 region in other gastrointestinal cancers, such as esophageal, gastric, and pancreatic cancers, has been reported, and D3 dissection is not recommended (9-11). As mentioned above, #253 complete D3 dissection with IMA root ligation has been demonstrated to increase colonic ischemia and postoperative complications and to have a worse prognosis compared to IMA-preserving D3 system dissection (12).

Objective

This study aimed to compare the outcomes of IMA root ligation in the #253 complete D3 dissection group (complete ligation group), IMA-preserving D3 system dissection (IMA-preserving D3), IMA-preserving #253 sampling, and D2 dissection up to #252+242 (#253 sampling/D2). Specifically, it sought to evaluate the survival outcomes, prognostic implications, and complications associated with complete IMA ligation versus left colonic artery (LCA) preservation in laparotomy, hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS) and laparoscopic surgery. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-815/rc).

Methods

This study included 172 patients with stage II/III primary sigmoid colorectal cancer who underwent radical resection at Tokai University Hachioji Hospital between April 2002 and December 2017. The study included a gender distribution of 108 males and 64 females. The average age was 65.6 years, with a median age of 67 years. Tumor localization (S + RS/Ra + Rb) accounted for 136/36 cases, while the distribution of stages II and III was 87/85, respectively. The treatment groups were divided into the IMA complete ligation group (94 cases) and the LCA preservation group (78 cases). The follow-up rate reached 71.51%, as determined by examining the 5-year postoperative data from electronic medical records. The IMA complete ligation group was characterized by cases where the root of the IMA was ligated and dissected according to tumor location, post-resection colon blood flow, and distance to the anastomosis. Conversely, the LCA preservation group involved cases where the IMA root was preserved, with either lymph node sampling dissected or ligation of the LCA branch at its terminus. Patients included in the study had the condition of the IMA root confirmed through surgical records and postoperative CT scans to assess for metastasis or recurrence. Under these conditions, the 5-year recurrence-free survival (5Y-RFS) and 5-year overall survival (5Y-OS) were calculated and compared. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (revised in 2013). Tokai University Hachioji Hospital is included in the Tokai University School of Medicine. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Clinical Research of Tokai University School of Medicine (No. 23R-111), and written informed consent was obtained after verbal explanation.

Statistical analysis

The 5Y-RFS and 5Y-OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences were compared with the log-rank test, where the hazard ratio (HR) [95% confidence interval (CI)] was applied. Additional tests employed included the χ2 test and Mann-Whitney’s U test. Statistical significance was established at P<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 25.0; RRID: SCR_016479; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

We included 172 patients with stage II/III primary sigmoid colorectal cancer who underwent radical resection at Tokai University Hachioji Hospital between April 2002 and December 2017. The number of patients who underwent laparotomy/HALS/laparoscopic surgery was 79/59/34, with HALS and laparoscopic surgery being slightly less common than laparotomy (P=0.002). There was no significant difference in 131/41 cases with or without postoperative chemotherapy (P=0.26).

Prognosis

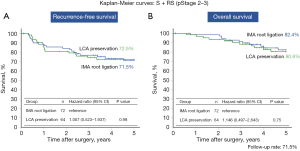

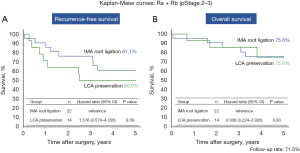

The 5Y-RFS in S + RS + Ra + Rb (n=172) was 69.1% in the IMA complete ligation group (n=94) versus 68.3% in the LCA preservation group (n=78) (P=0.75, HR: 1.093; 95% CI: 0.631–1.894) (Figure 1A). The 5Y-OS was 80.9% in the IMA group compared to 79.7% in the LCA group (P=0.84, HR: 1.075; 95% CI: 0.525–2.202) (Figure 1B). Neither of these differences were significant. Similarly, the 5Y-RFS for S + RS (n=136) was 71.5% in the IMA group (n=64) versus 72.5% in the LCA group (n=72) (P=0.98, HR: 1.007; 95% CI: 0.523–1.937) (Figure 2A), and the 5Y-OS was 82.4% in the IMA group (n=72) versus 80.6% in the LCA group (n=64) (P=0.75, HR: 1.146; 95% CI: 0.497–2.643) (Figure 2B). In both comparisons, the differences were not significant. Lastly, the 5Y-RFS in Ra + Rb (n=36) was 61.1% in the IMA group (n=22) versus 50.0% in the LCA group (n=14) (P=0.38, HR: 1.576; 95% CI: 0.570–4.356) (Figure 3A), and the 5Y-OS was 75.6% in the IMA group (n=22) compared to 75.0% in the LCA group (n=14) (P=0.93, HR: 0.938; 95% CI: 0.224–3.926) (Figure 3B). These differences were also not significant.

Background factors

The sex distribution was male/female: 108/64 cases in the IMA complete ligation group and 94/78 cases in the LCA preservation group (P=0.86). Mean age was 65.5/65.7 years in the IMA complete ligation/LCA preservation group, with a median age of 67.0 years in both groups. Tumor localization was 72/64 cases (136 cases total) in the IMA complete ligation/LCA preservation group for S + RS and 22/14 cases (36 cases total) for Ra + Rb. There were 51/36 cases (87 cases total) in the IMA complete ligation/LCA preservation group for stage 2 and 43/42 cases (85 cases total) in the IMA complete ligation/LCA preservation group for stage 3. Stage 3 included the IMA complete ligation group and LCA preservation group: 43/42 cases (85 cases in total). There was a significant trend towards fewer HALS and laparoscopic surgery procedures than laparotomy (P=0.002). All surgeries were performed by Mukai et al. to ensure uniformity of operative technique and technological advances (13). Perioperative chemotherapy was administered in accordance with the 2010 Guidelines for the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer (14).

There were no significant differences in operative time, blood loss, postoperative hospital stay, or number of patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy.

Postoperative complications

Regarding postoperative complications, postoperative anastomotic failure occurred in 8/4 patients in the complete ligation and LCA preservation groups, respectively. Postoperative hemorrhage was more common in the LCA-preserving surgery group (1/4). Postoperative wound infections were more common in the IMA complete ligation group (14/8). Dysuria was observed in 5/1 patients in the complete ligation and LCA preservation groups, respectively. Ureteral injury occurred in only one patient in the complete ligation group. Bowel obstruction was observed in 6/7 cases in the IMA complete ligation group and LCA preservation group, respectively (Table 1). No significant differences were found owing to the small number of complications (P=0.38).

Table 1

| Postoperative complications | IMA root ligation group | LCA preservation group |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete suture | 8 | 4 |

| Ileus | 6 | 7 |

| Wound infection | 14 | 8 |

| Bleeding | 1 | 4 |

| Dysuria | 5 | 1 |

| Ureteral injury | 1 | 0 |

| Others | 2 | 2 |

IMA, inferior mesenteric artery; LCA, left colonic artery.

Discussion

Key findings

In the present study of primary sigmoid colorectal cancer stage II/III, no significant difference in OS/RFS was found between the IMA complete ligation group with ligation and dissection of the IMA root and the LCA preservation group without ligation and dissection (including sampling) in terms of dissection of the lymph nodes of the IMA root (#253). No significant difference in OS/RFS was found between the complete IMA ligation and LCA preservation groups (including sampling). Because the prognosis usually tends to be better in S + RS cancers, the present study also examined the prognosis of S + RS and Ra + Rb cancers in Japan (15). Although there was no significant difference, there was a trend towards a lower RFS in the LCA-preserving group of Ra + Rb cancers. However, the lack of difference in OS was considered to be because of the small number of cases.

Strengths and limitations

Postoperative complications tended to be more common in the IMA complete ligation group, although there were no significant differences owing to the small number of cases. Suture failure occurred in 8 of 14 patients across the IMA complete ligation group and LCA preservation group. Notably, all eight patients in the IMA complete ligation group underwent stoma augmentation following a Clavien-Dindo classification of IIIb. In contrast, the four patients in the LCA-preserving group did not require stoma augmentation and showed improvement with conservative treatments, such as drainage techniques. Dysuria was observed in 5 of 16 cases across both groups, with ureteral injury occurring in only one case within the complete ligation group.

The results of the present study showed no significant differences in OS/RFS between D3 dissection with or without ligation and dissection of the IMA in cStageII/III sigmoid colorectal cancer. Although there were no significant differences in complications, the small number of cases and the possibility of conservative treatment in cases of suture failure suggest that sampling and preservation of lymph nodes at the root of the IMA without ligation and dissection may be a possible option from a safety perspective.

Comparison with similar research

Vascular treatment may be complex during the actual surgical procedure, and postoperative hemorrhage occurred more frequently in the LCA-preserving surgery group, though this difference was not statistically significant. Numerous studies have investigated the causes of anastomotic failure, considering factors such as (I) anastomotic blood flow; (II) tension at the anastomotic site; (III) anastomotic organs; and (IV) patient comorbidities (16).

In future procedures, based on the depth of the primary lesion, lymph node dissection of the IMA should be restricted to sampling for better prognosis and safety. Active preservation of the LCA is advisable to reduce anastomotic failure by maintaining the integrity of the remaining bowel tract. This approach may allow the selection of a technique to perform anastomosis safely without requiring colectomy or dissection around the splenic flexure. Herein, a summary of the results is provided.

While not investigated in this study, the presence or absence of blood flow in the Riolan artery arch at the Griffith point could have influenced blood supply to the residual intestinal tract. Recent advancements have enabled the preoperative visualization of vessels using contrast-enhanced CT scans (12,17). Therefore, it is necessary to consider blood flow in the same area during preoperative imaging (12,17). In recent years, it has been suggested that safe anastomosis can be achieved using indocyanine green fluorescence navigation to visualize blood flow in the oral intestinal canal and confirm blood flow at the anastomosis site, followed by anastomosis. However, iodine content is contraindicated in patients with iodine hypersensitivity because of its iodine content (18).

Explanations of findings

In Japan, D3 dissection is the standard technique for lymph node dissection, particularly focusing on IMA root dissection in the reflux zone, in cases where a preoperative diagnosis of lymph node involvement extending from part of the T2 (MP) to deeper levels or lymph node metastasis is suspected (2). The importance of total mesocolic excision/total mesorectal excision and CVL has also been reported in Europe and USA; however, the difference between these techniques and D3 dissection of the main lymph nodes in Japan remains unclear (3-6). Nonetheless, D3 dissection, where the IMA is ligated and dissected at the root, requires caution, given its proximity to important organs, such as the inferior abdominal plexus and ureters, which are at risk of damage. Moreover, although blood flow is maintained from the middle and inferior rectal arteries at the distal end, problems (ischemia/stasis) with residual bowel length and blood flow may occur in the mouth-side bowel, requiring dissection in the vicinity of the splenic curvature.

Implications and actions needed

Furthermore, in recent years, total neoadjuvant therapy (TNT), in which chemotherapy is administered before and after chemoradiotherapy (CRT), has been actively used mainly in Europe and USA. TNT is administered before or after CRT and has been shown to improve the rate of delivery, preoperative downstaging, and systemic control of micrometastases (19). Notably, TNT has the advantage of an improved performance rate in chemotherapy administered before and after CRT, preoperative downstaging, and early systemic treatment of micrometastases. In Japan, prophylactic bilateral dissection is recommended for Rb rectal cancer; however, it is thought to reduce the local recurrence rate but does not contribute to OS (JCOG0212) (20). There is a report of an increased response rate to TNT, which may lead to the possibility of further safe omission of lateral lymph node dissection in the future (21).

Conclusions

Based on the above findings, the present study suggests that preservation of the IMA may be safe and effective in stage II/III lymph node dissection for primary sigmoid colorectal cancer.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-815/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-815/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-815/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jgo-24-815/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (revised in 2013). Tokai University Hachioji Hospital is included in the Tokai University School of Medicine. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Clinical Research of Tokai University School of Medicine (No. 23R-111), and written informed consent was obtained after verbal explanation.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Japanese Classification of Colorectal, Appendiceal, and Anal Carcinoma: the 3d English Edition J Anus Rectum Colon 2019;3:175-95. [Secondary Publication]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hashiguchi Y, Yamaguchi S, Saito Y, et al. Japanese society for cancer of the colon and rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2022 for treatment of colorectal cancer. Tokyo: Kanehara & Co., Ltd.; 2022:16-8.

- Ueda K, Daito K, Ushijima H, et al. Laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation for splenic flexure colon cancer: short- and long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc 2022;36:2661-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ho MLL, Ke TW, Chen WT. Minimally invasive complete mesocolic excision and central vascular ligation (CME/CVL) for right colon cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol 2020;11:491-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sammour T, Malakorn S, Thampy R, et al. Selective central vascular ligation (D3 lymphadenectomy) in patients undergoing minimally invasive complete mesocolic excision for colon cancer: optimizing the risk-benefit equation. Colorectal Dis 2020;22:53-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perrakis A, Vassos N, Weber K, et al. Introduction of complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation as standardized surgical treatment for colon cancer in Greece. Results of a pilot study and bi-institutional cooperation. Arch Med Sci 2019;15:1269-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kitano S, Inomata M, Mizusawa J, et al. Survival outcomes following laparoscopic versus open D3 dissection for stage II or III colon cancer (JCOG0404): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:261-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yasutomi M, Arakawa K, Isomoto H, et al. General rules of clinical and pathological studies on cancer of the colon, rectum and anus. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. 7th ed. Mar 2006:10-4.

- Okusaka T, Nakamura M, Yoshida M, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for pancreatic cancer 2022. Vols. 169-171. Tokyo: Kanehara & Co., Ltd.; 2019.

- Baba E, Terashima M, Ono H, et al. Gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2021. Japanese gastric cancer association. Vols. 18-21. Tokyo: Kanehara & Co., Ltd.; 2021.

- Kitagawa Y, Ishihara R, Ishikawa H, et al. Esophageal cancer practice guidelines 2022 edited by the Japan esophageal society: part 1. Esophagus 2023;20:343-72.

- Ernst CB. Colon ischemia following abdominal aortic reconstruction. In: Bernhard VM, Towne JB. editors. Complication in Vascular Surgery. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1980.

- Mukai M, Kishima K, Tajima T, et al. Efficacy of hybrid 2-port hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (Mukai's operation) for patients with primary colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep 2009;22:893-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum: JSCCR Guidelines 2010 for the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Tokyo, Japan: Kanehara & Co., Ltd., 2010.

- Mukai M, Kishima K, Yamazaki M, et al. Stage II/III cancer of the rectosigmoid junction: an independent tumor type? Oncol Rep 2011;26:737-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujita F, Torashima Y, Kuroki T, et al. Risk factors and predictive factors for anastomotic leakage after resection for colorectal cancer: reappraisal of the literature. Surg Today 2014;44:1595-602. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Griffiths JD. Surgical anatomy of the blood supply of the distal colon. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1956;19:241-56. [PubMed]

- Watanabe J, Takemasa I, Kotake M, et al. Blood Perfusion Assessment by Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Imaging for Minimally Invasive Rectal Cancer Surgery (EssentiAL trial): A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Surg 2023;278:e688-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Aguilar J, Smith DD, Avila K, et al. Optimal timing of surgery after chemoradiation for advanced rectal cancer: preliminary results of a multicenter, nonrandomized phase II prospective trial. Ann Surg 2011;254:97-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujita S, Mizusawa J, Kanemitsu Y, et al. Mesorectal Excision With or Without Lateral Lymph Node Dissection for Clinical Stage II/III Lower Rectal Cancer (JCOG0212): A Multicenter, Randomized Controlled, Noninferiority Trial. Ann Surg 2017;266:201-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jin J, Tang Y, Hu C, et al. Multicenter, Randomized, Phase III Trial of Short-Term Radiotherapy Plus Chemotherapy Versus Long-Term Chemoradiotherapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer (STELLAR). J Clin Oncol 2022;40:1681-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]